When I was working at my Index of Japanese Swordsmiths, I frequently came across different kinds of mentioning certain forging techniques in a signature. First the easy ones. For example a wakizashi with the mei „Teruyoshi saku – shitagitae Hidekane“ (英義作・下鍛英兼), which means „Made by (Fujieda Tarô) Teruyoshi, foundation forging by Hidekane (who was Teruyoshi´s student but is mostly quoted with the reading „Hidekane“).“ Another example. There is a katana extant by Miyoshi Nagamichi (三善長道) whose mei on the ura side starts with „agegitae“ (上鍛), which means „final or finish forging.“ This practice was by no means uncommon, i.e. a master having his students forging the shitagitae, rare is only the explicite mentioning on the tang. So we can assume that such inscriptions honestly marked less expensive blades coming out of the forge where the buyer was now sure that the master at least gave the finishing touches. (Note: More details about shitagitae and agegitae can be found in Kapp and Yoshihara´s standard work The Craft of the Japanese Sword.)

Another rather frequently found term on sword tangs is „shin no kitae“ (真の鍛) or „shin jûgo-mai kôbuse tsukuru“ (真十五枚甲伏造). The former is seen for example occasionally on blades of Kotetsu (虎徹) and the latter on works of Ômura Kaboku (大村加卜), his student Bokuden (卜伝), Suishinshi Masahide (水心子正秀), the 2nd generation Shitahara Toshinaga (下原利長), Hamabe Toshinori (浜部寿格), or Musashi Tarô Yasukuni (武蔵太郎安国). Usually shin no kitae is translated as „carefully forged“. As this process takes a great deal of time and effort, the translation is not off but there is more than just „carefully forged“. The famous sword tester Yamano Ka´emon (山野加右衛門) wrote namely in his rare script „Tetsutan-shû“ (鉄鍛集) that for shin no kitae, high-quality steel from Izuha (出羽) of Iwami province is used and mixed with a small amount (5 monme ~ 19 g) of old iron from anchors and the like. This mix of iron pieces is piled up in the usual way of a loose block (mizubeshi, 水減し) and then forged and folded crosswise. Note: Like Shiso (宍粟) in Harima province, Izuha was known since oldest times as production site of high-quality iron or steel respectively.

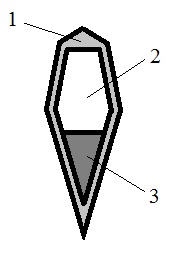

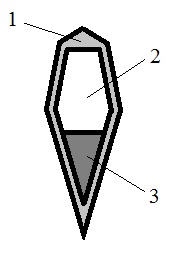

Well, the term shin jûgo-mai kôbuse tsukuru has nothing to do with shin no kitae. The one who started to apply this technique was the aforementioned Kaboku. In his publication „Kentô-hihô“ (剣刀秘宝) he explains that he used three different kinds of steel for this forging technique, namely two kinds of core steel, shin-jitetsu (心地鉄, lit. „basic core steel“) and shin-hatetsu (心刃鉄, lit. „cutting-edge core steel“), and one kind of skin steel which he called tsurabuse-uwatetsu (面伏上鉄, lit. „bent over surface steel“). First he prepared the soft shin-jitetsu like the well-known shingane (core steel). Then he made the shin-hatetsu of high-quality steel from Izuha and/or Shisô which is still soft but a bit harder than the shin-jitetsu. The shin-jitetsu is put atop of the shin-hatetsu and both steels are forged together. As a final step, the hard tsurabuse-uwatetsu is completely wrapped around this package (see picture 1). Thus we have here still a kind of kôbuse, the famous U-shape, but where the shingane consists of two kinds of steel of different hardness and the kawagane covers also the later back of the blade. The jûgô-mai is explained by the fact that the shin-jitetsu is folded fifteen times to make it considerably soft. That means „shin jûgo-mai“ is here an abbreviation of „15-times folded shingane“. It is now assumed that this forging technique was developed by Kaboku either to achive the most durable sword or to rediscover old and forgotten kotô forging techniques. I would tend to the former approach because unlike forging methods like hon-sanmai-awase or shihô-zume, a kôbuse or Kaboku´s version of a kôbuse does not necessarily have that big effect on the later appearance of the finished sword (i.e. the way the jigane interacts with the habuchi and yakiba for example). In turn, the later shinshintô master Suishinshi Masahide who had a strong theoretical approach to swords, was inspired by Bokuden´s publications and so it is no wonder that he too experimented with the shin jûgo-mai technique.

Picture 1: Cross-section of a shin jûgo-mai kôbuse blade of Kaboku. 1. tsurabuse-uwatetsu, 2. shin-jitetsu, 3. shin-hatetsu

A slightly different shin jûgo-mai technique was applied by the shinshintô smith Sasaki Ichiryûsai Sadatoshi (佐々木一流斎貞俊). He signed namely with the supplement „shin jûgo-mai futo-hirafuse“ (真十五枚太平伏). Hira-fuse referred in contrast to kôbuse to the forging technique of makuri-gitae (捲り鍛え), where the shingane is layed atop of the kawagane and then folded together so that the kawagane encloses the shingane in the known U-shape. In short, Sadatoshi used 15-times folded shingane for his hira-fuse/makuri-gitae technique. Somehow unclear is the term „futo“ (太) which means „thick“. So either a thick layer of shingane was used or „futo-hira-fuse“ was back then one single term to express a makuri-gitae.

Most of the other forging techniques like maru-gitae, muku-gitae, makuri-gitae, hon-sanmai-awase-gitae or shihô-zume-gitae are described and depicted elsewhere. I did not want to hash and rehash all the stuff published but focus on the few lesser known forging techniques in this very first article.