This time I want to introduce a Natsuo tsuba which is not “just” a great masterwork like they all are but which is oustanding as it marks a very important stage in his career.

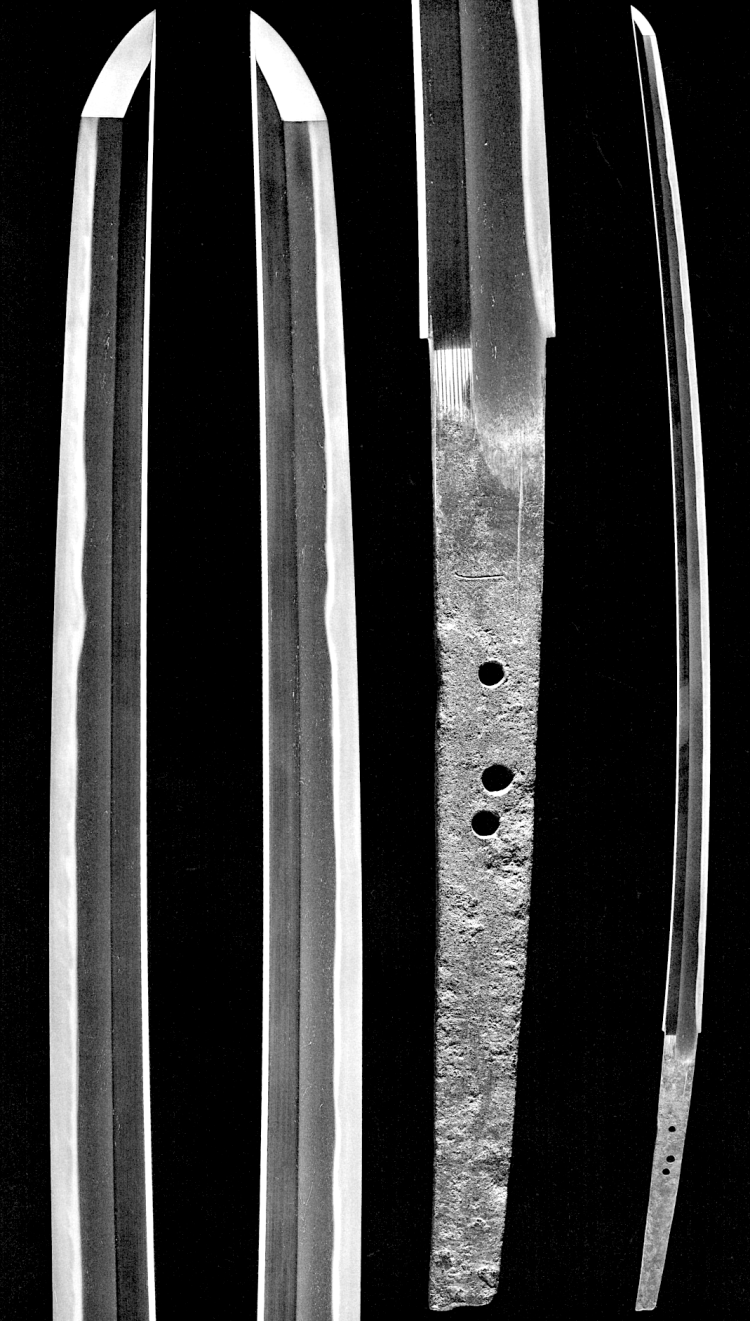

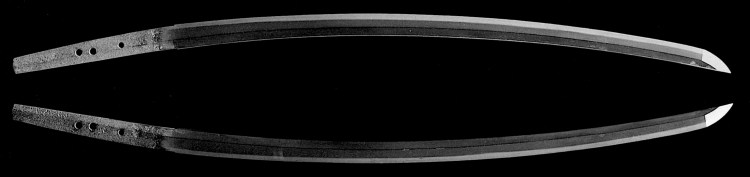

The above shown tsuba has the motif of the God of Luck Jurōjin (寿老人) riding a crane on the omote and young pines on the ura side. It is of shakudō, has a nanako ground, and makes much use of empty space. Jurōjin on his crane is interpreted in a quite three-dimesional manner, jutting out in a relatively prominent from the ground plate. Jurōjin is regarded as auspicious, as is the crane, as are young pines. So just from the motif of motif elements alone we have triple auspiciousness so to speak. Highly elegant is also how Natsuo plugged the one hitsu-ana with gold as part of the design and has the nanako and parts of the motif running over it. That is, to emphasize the optical or rather perceived fact that Jurōjin is indeed flying on a crane, a reference point is required. Now you can just add for example treetops to create a sense for height, i.e. flying, but often the perception of flying high in the sky was achieved via the sun or the moon in the background. But instead of merely adding a flush hira-zōgan of the sun or lunar disc, Natsuo so to speak made use of the common practice of plugging hitsu-ana and turned that into the sun so to speak, what is in my opinion a highly elegant approach as stated above.

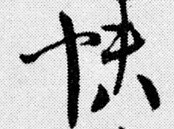

So far, so good, very nice tsuba you will all agree on, but why is it sp special? Well, for this, we first have to take a look at the signsture, which reads: “Kōka san no toshi taisō shokyū – Ōtei-sōka Toshiaki + gold seal ” (弘化三暦大簇初九・鶯蹄窓下寿良), “humbly made by Toshiaki on the ninth day of the first lunar month, spring, of Kōka three (1846)”. First of all, the ninth day of the first lunar month is an auspicious day as it is the birthday of the Jade Emperor who is also revered in Buddhism, what adds quasi a fourth layer of auspiciousness to the tsuba (i.e. Jurōjin, a crane, and young pines being the other three).

The more advanced kodōgu enthusiasts, and readers of my book(s) on Natsuo may know, Toshiaki (寿良) was the early name with which Natsuo signed. Now let me introduce his career up to the time this tsuba was made so that we get some background for its importance. Natsu was born on the 14th day of the fourth month of Bunsei eleven (文政, 1828). In Tenpō ten (天保, 1839), he started an apprenticeship with the kinkō artist Okumura Shōhachi (奥村庄八). Okumura was a Gotō-trained guy and so he learned from him first and foremost the proper application of nanako, the making of menuki, gilding and silvering via techniques like kingise, ginsise, iroe or okigane, and the production of ground plates for kozuka. Training under Okamoto was not enough because after just about one year of learning, it was in Tenpō eleven (1840), he left his workshop and entered an apprenticeship with Ikeda Takatoshi (池田孝寿) from the Ōtsuki school (大月). The Ōtsuki school was a renowned lineage of kinkō artists founded in the mid-18th century in Kyōto. The school followed initially the classical style of the Gotō school but then became famous when its fourth master Mitsuoki (光興, 1766-1834) started to study painting under contemporary masters like Ganku (岸駒, 1749/1756-1838) and Nagazawa Rosetsu (長沢蘆雪, 1754-1799) from the Maruyama school (円山). This means that later in his career Mitsuoki applied more and more novel motifs and tried fresh interpretations strongly inspired by his training as a painter.

Takatoshi’s father Ikeda Kyūbei (池田久兵衛), who signed with Okitaka (興孝) and later with Takaoki (孝興), was a student of Mitsuoki but it is said that also Takatoshi studied directly with the fourth Ōtsuki master. Natsuo later said that under Takatoshi he spent two whole years, among other things of course, practicing katakiribori basics following copper plates designs given to him by his master. This practice helped him a lot and so his master decided it was time to grant him the character for Toshi from his own name whereupon Natsuo took the craftsman name Toshiaki (寿朗). He was 15 years old at the time.

While practising kinkō he also studied classical Chinese in the morning under Tanimori Shigematsu (谷森重松), and in the evening painting under Nakajima Raishō (中島来章, 1796-1871) from the Maruyama-Shijō school (円山四条). His master Raishō even suggested that Natsuo should become a painter but he stayed with the kinkō art which mas more to his liking. Well, as Natsuo was born rather weak, his adoptive mother Miyo (みよ・美代) was initially against his wish to become a kinkō craftsman. Instead she made him learn to play the shamisen but Natsuo later told his students that he stopped that very early because it was absolutely not his thing.

After five years of training under Takatoshi, the master realized the great progress his promising student had made and entrusted him for the first time with works for customers for which he could refine his takabori and kebori techniques, the first of them being menuki in the form of flying cranes, a fuchigashira set with a turtle motif, a kozuka with kebori of bamboo, and a tsuba showing young pines.

And now we arrive at where the tsuba introduced here was made. In Kōka two (弘化, 1845), i.e. when he was 17 years old (or 18 according to the Japanese way of counting years), Natsuo decided that his craft was advanced enough to leave his master Takatoshi, and just one year later he took the risk to open up his own business in the old cultural capital Kyōto. In other words, the tsuba in question was made by Natsuo when he was just 18 years old (or 19 according to the Japanese way of counting years) and most likely the piece with which he celebrated his going into business for himself. It is now possible that he was comissioned with it by an affluent client, so to speak as form of support to get his business started, and we know that often clients left the motif of the work to the artist. That is, maybe Natsuo’s very first client told him he is going to pay him good money for a nice tsuba, as support for his craft, and that it just should depict something auspicious, maybe something with the upcoming New Year in mind. Or, Natsuo came up with everything for himself and thus placed so much auspiciousness into it, i.e. as a relatively safe bet to find a paying customer as auspicious motifs of course never go out of fashion.

Be that as it may, after leaving his master Toshitaka, Natsuo was basically an autodidact. In Kaei two (嘉永, 1849), when he was 21/22 years old, he gave up the craftsman’s name Toshiaki in favour of Natsuo. His student Okabe Kakuya (岡部覚弥) later quoted Natso upon describing the times of his name change: “When I was twenty-two or twenty-three I experienced a first sense of maturity when carving kozuka with the motif of a tiger carrying his cubs over the river and fuchigashira showing hares and waves, as these pieces were so much praised by everyone who saw them.”

However, when he was twenty-five he had the feeling that Kyōto might not be the best place to unfold his talent as “so many people wore ceremonial court dresses and were just into fabrics and patterns.” So, he made plans to try his luck in Edo, the capital and the center of the bushi class. On the second day of the tenth month of Ansei one (安政, 1854) he borrowed 20 gold pieces from his adoptive mother and left Kyōto with his friend Chūshichi (忠七) and took with him a tsuba with the motif of the Oath of the Peach Garden into which he had put his entire heart and sold, to use as a demonstration piece to show his abilities in Edo. The rest of his career is described in detail in my book on Natsuo here.

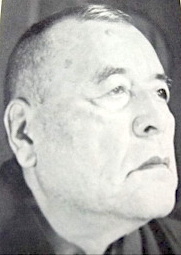

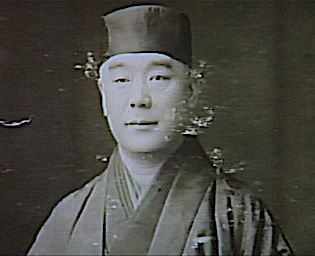

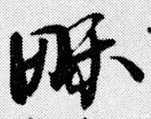

Above is a picture of the young Natsuo. I do not know how old Natsuo was at the time it was taken but I assume it is pretty close to when the tsuba introduced here was made. So in conclusion I want to say that this tsuba would surely make a very very nice cornerstone of every Natsuo collection. I do not know who the owner of the tsuba is but he must be very proud of owning this, in my opinion very special by and for Natsuo.