The eBook version of the just revised Index of Japanese Swordsmiths is now available as e Swordsmiths of Japan (see link here). I made a revision, not an entirely new book, so everyone who has purchased the initial e Index of Japanese Swordsmiths should be able to download the revised edition from their Lulu account for free. However, Lulu changed their eBook publishing system a while ago and those who got the e version of this publication before that time were quasi cut off from future free downloads of revisions. So my suggestion: All those who purchased the e Index of Japanese Swordsmiths, please try to download the revision. If it works, everything is fine as you got it after the change. If it says “This eBook is no longer available for download.”, please get in touch with me via “markus.sesko@gmail.com” and I will provide you with further information about how you get your free revision via a filesharing programm. I kindly ask you to provide me with any info that you indeed got the initial eBook. This is just to keep handing out free copies within limits as this project represents years of hard work and should therefore be remunerated accordingly. I will not stubbornly insist on any “hard evidence” and handle this on the basis of trust. Apart from that, I will keep your emails on file so that I can provide you with any further updates in the future. Thank you.

Author Archives: Markus Sesko

NEW: SWORDSMITHS OF JAPAN – 3 Volumes

It’s done. The revised and enlarged three-volume hardcover set SWORDSMITHS OF JAPAN AKI-KUNI, KURA-SANE, and SATO-ZEN, formely titled Index of Japanese Swordsmiths, is out now and finally easily available outside of Europe! It is letter format, black & white on cream paper, a tan linen hardcover with a glossy dust jacket, and each volume has about 500 pages. The real thing looks, except for the changed title, pretty much like my test print introduced earlier here (or see picture below).

As for kotō, shintō, and shinshintō smiths, this publication qotes the wazamono ranking that goes back to revised edition of the 1815 published list of wazamono of the Kaihō Kenjaku (懐宝剣尺), and the so-called Fujishiro Ranking used by Fujishiro Yoshio and Matsuo in their 1935 publications Nihon Tōkō Jiten – Kotō Hen and Nihon Tōkō Jiten – Shintō Hen. When it comes to gendaitō and especially WWII-era smiths, this publication includes the ranking of about 300 contemporary smiths carried out by Kurihara Akihide (栗原昭秀) in 1942 under the title Seidai Tōshō Iretsu Ichiran (聖代刀匠位列一覧). In addition, also the five ranks and the special rank of the sixth national sword making contest, the Shinsaku Nihontō Denrankai (新作日本刀展覧会), from 1941 are quoted where about 250 swordsmiths were awarded. Apart from that, I also added the info if there are blades designated as kokuhō and/or as jūyō-bunkazai by a smith (marked by two different symbols).

As indicated in my update posted the other day, I am now more flexible with pricing and offer the set for 179.70 USD (59.90 USD each) instead of the initial 280 USD for the two-volume set. Also the timing is pretty good right now as there are four days left of Lulu’s Mother’s Day sale that saves you 20% on print books. So please use code MOM20 until May 10th to make use of this great offer. Please give me a few more days to finish the eBook version as I have to unite the three volumes into one file.

Links to the books are found below (please click on preview of the first, i.e. the AKI-KUNI copy to lean about the new layout):

Supplement:

The dust jacket version only ships from the US so there is also an “international” version (marked by the supplement “intl.”) that comes as standard casewrap hardcover. Please see link below:

International Volume 1: AKI-KUNI

International Volume 2: KURA-SANE

International Volume 3: SATO-ZEN

*

Preface to the Revised Edition:

“Three years have now passed since I published my two-volume Index of Japanese Swordsmiths and, although it seems to be a pretty short period of time for a second edition, it was indeed necessary for several reasons. First of all, the English version contained left-over fragments of the German version and just too many typos that were missed in the proofreading. This brings us to the second reason for the early update, the layout. It was brought to my attention that the font was just too small to work comfortably with the two volumes. And the third and most important reason for the early update is the fact that the initial English version was never made available to the international market as it was supposed to be. After struggling with makeshift options to make the set accessible to non-European readers, and with the aforementioned shortcomings in mind, I decided that it was time to tackle a revision. First of all, the layout was changed and a different, larger-sized font and even larger capitalized headers (i.e. smith names) which mark each entry were chosen. Due to new reference material not available at the time the initial edition was published, the revised edition was enlarged by more than 300 gendaitō, but of course several other smiths were also added who were missed the first time round. In addition, historic portraits of smiths, about 400 photographs of contemporary smiths, and pictures that contribute to the understanding of an entry were added. This resulted in an increase of about 600 pages which therefore made it necessary to split it up into three volumes. I also integrated the overview of nyūdō-gō used by the swordsmiths to enable the (non-ebook) reader to find smiths on the basis of their pseudonyms. Last but not least, a different title had to be chosen, on the one hand because the now longer set represents more of an encyclopedia of swordsmiths rather than an index, and on the other hand to avoid issues and confusion with the initial publication. With this, I hope that the revised and enlarged Swordsmiths of Japan becomes the standard work in the West for research on Japanese swordsmiths as it is still the only comprehensive non-Japanese publication of its kind.

Early Summer 2015

Markus Sesko”

KANTEI 2 – JIGANE & JIHADA #1

With this post, we are entering the second step in kantei, following the traditional approach indicated at the very beginning of the series (i.e. sugata → jigane → hamon). As mentioned back then, the steel – jigane (地鉄) – allows us in the ideal case to identify the area of production and/or the school. Well, things are of course fluid, that means everything from so “featureless” that it is even hard to tell if kotô, shintô, or shinshinto to a very characteristic steel or forging structure that allows you right away to name the smith who made the blade is possible. This brings us to the point where I have to mention that the chapter jigane actually consists of two chapters, that is to say the already mentioned steel, the jigane, and the forging structure, the jihada (地肌), or short just hada.

*

2.1 Jigane

Before we start, we have to address a crucial point when it comes to jigane, namely the polish. Depending on factos like the age of the polish, the skill of the polisher, and the use of various ways to finish the ji, the appearance of the jigane can vary greatly, even if you are comparing two indentically interpreted blades from the same smith side by side. So my tip is, try to focus on what should be recognisable regardless of the finish of the polish, and that is the density and the pattern of the forging structure. Well, this tip does not work when the polish is too old or bad, and if you can’t see any details in the steel, you have to skip this step anyway. Rule of the thumb is: The more uniform the jihada, the better the skill of the smith. That means a jihada might be mixed with areas of different forging structure but these areas should never stand out in an unnatural manner. So if you have a blade with a tight hada all over that shows very coarse, rough, or inhomogeneous structures just in one area, you can assume that this was not intended, i.e. that the smith lacked skill. Another possibility is that you recognize areas that don’t show any visible forging structure at all or areas without a visible forging structure that are surrounded by rougher, standing-out areas. If so, it is very likely that the core steel (shingane) comes through and that the blade had seen some polishes in its life. Please note that certain similar appearances might actually be characteristic features of a certain school or smith but this will be pointed out below or in the individual chapters. A quality feature that mostly goes hand in hand with the uniformity is the fineness of the hada but that does not mean that a larger structured hada is of a lesser quality. In other words, a swordsmith was “embedded” into his scholastic background what means that a Yamashiro man followed a different approach in forging than a Sôshû man. So the outcome, i.e. the degree of uniformity and constant quality speaks for the skill of a smith and not the technical approach in general.

So first of all, let me introduce the standard terms that have become established to refer to the different appearances of the jigane and the jihada. Basically we use the prefixes ko (小) and ô (大) to say if a forging pattern is noticeably smaller or larger strictured respectively. For example, an itame-hada can appear as ko-itame, as itame, or as ô-itame, that means here it got common to refer to a medium-sized forging structure just by its name and not to as by the prefix chû. There are of course schools of thought, like for example at the Hon’ami school, where they explicitly speak of a chû-itame or chû-mokume but today, most drop the prefix chû in this respect. Apart from distinguishing between a ko, normal-sized (chû), or ô forging structure, we also speak of a fine or dense hada, in Japanese komakai (細かい) or tsunda (詰んだ). Or also terms like seibi (精美) are in use to refer to a hada that is very fine and beautiful. Well, I am aware of the fact that there are subtle differences between a “fine” and a “dense” hada but I don’t want to overcomplicate it for the moment. The opposite of a fine hada is a rough (arai, 荒い・粗い) or standing-out (tatsu, 立つ) hada. That means in such a case, the individual layers of the steel are clearly visible. Again, a “rough” hada is not the same as a “standing-out” hada as the former term is more used to describe an “unnaturally” rough hada and the latter to refer to something that was intended by the smith, i.e. a result of his approach in forging the steel. Besides of that and not addressing the forging structure but the steel itself, we also speak of a strong (tsuyoi, 強い) jigane when the jihada is very visible at a glance and accompanied by plenty of ji-nie. A strong jigane is usually associated with blades made in the Sôshû tradition where the large amount of ji-nie and chikei result in very present features. The opposite of that is a weak (yowai, 弱い) jigane where the jihada is hardly visible and shows no or only very little ji-nie. Basically, and with the exception of certain schools (e.g. the Kiyomaro school that revived the strong Sôshû jigane), shinshintô blades are described as having a weak jigane as not much is visible in their steel. But there is more when it comes to describe the appearance of the jigane. The steel can also be either clear (saeru, 冴える) or subdued (shizunda, 沈んだ) whereas in the latter case we also speak of a “dull” or “cloudy” (nibui [鈍い] or nigotta [濁った]) jigane. Dull or cloudy means that a steel remains to be matt in larger areas even if polished. Or in other words, even if it is tried to enchance the ji with certain polishing methods, a dull or cloudy steel will never turn out to be super bright. And when the steel looks “wet,” i.e. kind of moisty even if perfectly freed from oil, we speak of uruoi (潤い). And last but not least we distinguish between a noticably dark or blackish (kuroi, 黒い) or whitish (shirake, 白け) steel. The former is typical for blades from the farther north or south regions, that means from the so-called Hokkoku region (北国, production sites along the Hokurikudô) or Kyûshû respectively. Accordingly, also the term hokkoku-gane (北国鉄) is in use to refer to a darker, “northern-style” jigane. As for shirake, basically later Mino, i.e. Sue-Seki blades are known for showing much shirake but a little shirake is seen at many other schools and this will be pointed out in the individual chapters. By the way, shirake is often a way to distinguish offshoots from the schools they came from. That means, if you have for example a blade that looks like Rai at a glance but that just shows too much whitish shirake in the ji, think about a school that derived from Rai, e.g. Enju or Ryôkai. And the overall quality of the work should tell you how far away you are from the “real thing,” i.e. are you facing a direct student of one of the great masters? Or is the workmanship already that inferior to assume that it is a work of a student of this student or of an even later smith from a local offshoot?

In direct continuation of talking about the steel, I want to introduce first the features, the hataraki that can occur in the jigane before introducing the different forging structures. Well, strictly speaking, some of them might be associated with the jihada but they should be introduced here too for reasons of clarity and convenience.

ji-nie (地沸): Ji-nie is probably the most common feature in the jigane and seen to some extent in any sword. As the term suggests, we are talking about visible martensite particles (nie) that occur in the ji. Ji-nie can be pretty fine and evenly distributed over the blade or concentrate in certain areas and if these areas appear in a connected manner over a certain distance (or along the entire ji for example), i.e. in a way to recognize a certain “unity” or patch, we speak of a nie-utsuri (but please see section utsuri for more details on this term). As for ji-nie, the same rule applies as for the jigane, that means we speak of a high-quality ji-nie when it is fine and uniform or when it was deliberately applied, i.e. when for example a partially rough and accumulating ji-nie was the style in which the smith worked. Also we must distinguish between if a sword was intended as mere weapon or if there was a real artistic approach behind making that blade. So if you have a late Muromachi-era blade from one of the then sword centers that shows rough and unnaturally accumulating ji-nie, it is safe to assume that smith was just lacking skill. But if you have a shinshintô blade with a rough and unnaturally accumulating ji-nie that should somehow represent a work from one of the great Sôshû masters, the element “lack of skill” has a slightly different connotation. In other words, the smith might had been indeed very skilled but than Sôshû was not his thing or he just started to experiment towards Sôshû. So depending on what the intention of making a blade was we have here different standards of appreciation. Just one example, very rough and obvious ji-nie is “accepted” for the Satsuma smiths because this was their style.

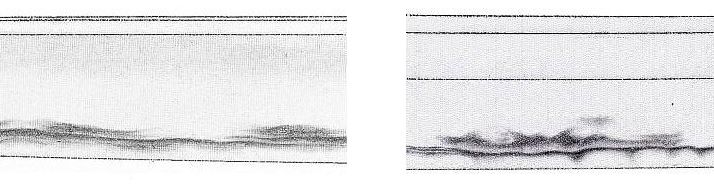

chikei (地景): Chikei are black gleaming lines in the ji that are basically layers of steel with a different, higher carbon content. So chikei follow the layer structure of the jihada and are virtually the same as kinsuji, just with the difference that they occur in the ji and not in the ha. As a rule of thumb: The more chikei are present the more it is likely that a blade was made following the Sôshû tradition of sword forging, i.e. deliberately mixing steels of different carbon content. Please note that there is also another way the term chikei can be used and that does not refer to layers of steel but to a hardening effect. In other words, it is used to refer to ji-nie that forms formations similar to mokume-like burls but which are not tied to the layer structures of the jihada. Well, some say that they actually are tied to the layers and we are speaking here of the same thing, i.e. the former explanation of chikei used to refer to the “obvious” layers of different carbon content in the steel and the latter to much finer layers which are not recognizable for the naked eye as layer structures and thus seem not to be connected to the structures of the jihada. But I don’t want to split hairs here (the subject of chikei might fill a blog entry itself) and when I refer to chikei, I mean black gleaming lines in the ji, period. (Please click on pic below to get a larger and clearer image).

yubashiri (湯走り): Yubashiri are isolated spots or patches of ji-nie that remind of water droplets. They are similar to tobiyaki as they occur detached from the hamon but as they consist of nie and are not embedded into a cloud of nioi, they have a more transparent look and not so clear borders as nioi-based tobiyaki. Due to the fact they consist of nie, yubashiri are of course seen on blades that are hardened in nie-deki or at least with much nie. So they are similar to tobiyaki but not the same. Yubashiri often concentrate along the habuchi and create there more linear appearances that remind of nijûba. We see them on Kamakura-era Yamato, Yamashiro, or Sôshû works or at later blades aiming at such works.

jifu (地斑): Jifu are areas where ji-nie occurs as a “closed mass,” i.e. as patch or stain. For example, we find descriptions like “plenty of ji-nie that tends to jifu in places” what basically means that these areas full of concentrated ji-nie give the blade a spotted appearance. But the term jifu, lit. “spot/splotches on the ji,” is rather ambiguous and different scholars use it to refer to different features. For example, some refer with it to areas of exposed shingane, for which in turn the special term ji-zukare (地疲れ) exists. And the “showing through” (sunda, 澄んだ) shingane in turn resulted in the creation of the term sumigane (澄鉄) or sumihada (澄肌). Another term for the same feature is, in special context of the Aoe school, namazu-hada (鯰肌) as these patches remind of the slimy, scaleless, smooth and dark skin of a catfish (namazu). And also the term Rai-hada (来肌) is in use when it comes to Rai blades with this characteristic feature. In other words, these terms were born from the necessity to name similar features differently depending on which school it occurs so that you have a more sophisticated nomenclature to work with. In a nutshell, when someone talks about “dark spots in the ji” it might be difficult to know what is meant but when this person uses the terms namazu-hada, or Rai-hada, everybody knowns right away that he or she is talking about Aoe or Rai blades respectively. It is assumed that the feature sumigane, namazu-hada, or Rai-hada goes back to the fact that the corresponding schools made blades with a relative thin kawagane what exposes the shingane core steel rather quickly. Well, there is still discussion about if these features, or Rai-hada in particular, are exposed core steel or just inhomogeneous but in itself homogeneous and darker parts of the steel but from my subjective point of view, I think they might be shingane but with the difference that we are talking here about top quality blades what in turn leads me to think that even their core steel was of better quality and looks thus slightly finer when exposed and not at a glance like ji-zukare for example seen on a Sue-Seki blade. Anyway, this feature, i.e. sumigane, is also found on blades of the Un group (雲), the Enju school (延寿), the Mihara school (三原), of Osafune Motoshige (元重), and on early Echizen blades like for example of Chiyozuru Kuniyasu (千代鶴国安) and Hashizume Kunitsugu (橋爪国次).

*

In conclusion it must be repeated that the jigane is a pretty sensitive subject and it needs some experience to be able to disregard or block out the condition of the polish and draw conclusions on what you would see with a perfect polish. That means certain features like yubashiri or finer ji-nie might just not be visible at an older polish. In other words, and this might make me sound like captain obvious, you should focus on what you see, i.e. you should not get lost in trying to figure out if a certain stain is yubashiri or jifu when the condition of the blade just does not allow such a conclusion. Also there are kind of preferences when it comes to judging Japanese swords: Some (like me) attach great importance to the sugata whilst others have a natural access to the steel and just need to look at the jigane and jihada to say which school or smith made the blade. And last but not least it turned out at our local sword meetings that light from a fluorescent tube is very good to see the steel (but not certain details of the hamon) but also sunlight does a pretty good job.

In the next part (2.1) we continue with the different forms of jihada, followed by a chapter on utsuri, before we end part 2, the steel, and go over to part 3, the hardening.

Index of Japanese Swordsmiths – Update

Apart from the eBook version, the poll has shown that by far most are preferring a three volume option that is enlarged with pictures. I ordered a proof copy the other day just to see how this might work and I have to say, I am pleased with the result. It is letter format, black & white on cream paper, a tan linen hardcover with a glossy dust jacket. The pictures below show the test run with about 700 pages so you have to think of about 200 less and imagine the result as three volumes 🙂 That will be the final version I guess. As for the revision, I added quite a bunch of smiths and about 300 gendai smiths and updated the info of about 500 of the gendai guys (due to new material I gathered for the upcoming Gendai project). Also I decided to add illustrations as mentioned but I refrain from posting pictures of blades, at the one hand as a single pic of a blade is mostly not helpful anyway, and on the other hand as this decision provides a good point to stop. That means a small illustration of a characteristic feature of a hamon is ok but adding randomly blade pictures here and there just unneccessarily bloats the project. Also new is a list of gô that I will add, i.e. you are now able to look up all smiths who used for example the gô “Ikkansai” and so on (well, this is more a practical plus for the print books). Below I will present some pics of the proof copy so that you can get a better idea of what this project might look like when finished. Well, I am not sure if I will keep the title Index of Japanese Swordsmiths because on the one hand, the revised edition does no longer feel like an “index,” and on the other hand, it will interfere with the contract I still have with BoD for the initial version and which is not terminable until later this year. So take a look at the pics and feedback is greatly welcomed (still work in progress so nothing too late). Thank you for your attention and the next part of the Kantei series should be online in a bit.

KANTEI 1 – SUGATA #8

We conclude the chapter on sugata with the changes in the shapes of wakizashi.

*

1.32 Muromachi period (1394-1572)

The “typical” wakizashi as we know it, i.e. in shinogi-zukuri and showing about the same proportions as a katana, did not appear before the Muromachi period and shinogi-zukuri wakizashi remain very rare until the mid-Muromachi period as in early Muromachi times, the hira-zukuri wakizashi was prevailing. The Muromachi gave anyway rise to many different wakizashi forms: shinogi-zukuri wakizashi with a nagasa of 45~55 cm, a noticeable taper, a shallow sori with a tendency towards sakizori, and a chû-kissaki; hira-zukuri wakizashi with the about the same nagasa and with a noticeable sakizori; and wakizashi in shôbu-zukuri and unokubi-zukuri which usually stay under 50 cm in length. Virtually every Muromachi-era school and smith made wakizashi and it is difficult to forward a name being representative for a certain sugata. Also we must not forget that shinogi-zukuri blades with a nagasa of just a little under 2 shaku (60.6 cm) from before the early Edo period were intended as uchigatana or katata-uchi and are only today – because of their length – classified as wakizashi.

Picture 32: different wakizashi styles from the Muromachi period (from left to right): mei “Morimitsu” (盛光), Ôei-Bizen, nagasa 52.9 cm mei “Yoshisuke” (義助), Shimada, 2nd generation, nagasa 44.2 cm, sori 1.2 cm mei “Bizen no Kuni-jû Osafune Gorôzaemon Kiyomitsu” (備前国住長船五郎左衛門 清光), dated Tenbun eight (天文, 1539), nagasa 51.8 cm, sori 1.2 cm mei “Kanemune” (兼宗), Sue-Seki, around Tenbun (天文, 1532-1555), shôbu-zukuri, nagasa 52.1 cm, sori 1.2 cm

*

1.33 Momoyama to early Edo period (1572-1624)

With the Nanbokuchô revival trend of Momoyama times, there were still quite many hira-zukuri wakizashi and hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi made. That means the classic shinogi-zukuri wakizashi did not replace them in terms of quantity yet. But of course an increasing number of shinogi-zukuri wakizashi can be seen from about Tenshô (天正, 1573-1592) onwards.

Picture 33: wakizashi from the Momoyama to early Edo period (from left to right): mei “Mutsu no Kami Daidô” (陸奥守大道), dated Tenshô 18 (天正, 1590), nagasa 43.9 cm, sori 0.3 cm mei “Bushû Shitahara-jû Terushige saku” (武州下原住照重作), 2nd generation, around Tenshô, nagasa 44.5 cm, sori 0.8 cm mei “Kanenobu saku” (兼信作), 1st generation, Kan´ei (寛永, 1624-1644), nagasa 54.0 cm, sori 1.2 cm mei “Fuyuhiro saku” (冬広作), around Kan´ei (寛永, 1624-1644), nagasa 46.2 cm, sori 1.5 cm

*

1.34 Advanced early Edo period (1652-1688)

Wakizashi from that time feature like their katana counterparts a Kanbun-shintô-sugata, that means they have a nagasa of about 45~50 cm, taper noticeably, and end in a compact chû-kissaki. All schools of that time made such wakizashi and it is hard to name any representative smith.

Picture 34: wakizashi from the advanced early Edo period (from left to right): mei “Higo no Kami Kuniyasu” (肥後守国康), nagasa 54.8 cm, sori 0.6 cm mei “Echizen no Kami Minamoto Sukehiro” (越前守源助広), 2nd generation, nagasa 45.4 cm, sori 0.6 cm mei “Nagasone Okisato Nyûdô Kotetsu” (長曽祢興里入道乕徹), nagasa 45.4 cm, sori 1.0 cm mei “Nagasone Okisato Nyûdô Kotetsu” (長曽祢興里入道乕徹), nagasa 49.8 cm, sori 0.8 cm

Certain renowned master smiths from the advanced early Edo period also made some flamboyant wakizashi. These were mostly made on special orders and are wide and impressive, that means they don´t follow the then Kanbun-shintô-sugata, and usually show elaborate horimono. Representative for this trend was for example Kotetsu.

Picture 35: elaborate wakizashi from the advanced early Edo period (from left to right): mei “Dôsaku kore o horu – Nagasone Okisato Kotetsu Nyûdô” (同作彫之・長曽祢興里古鉄入道), nagasa 49.2 cm, sori 1.2 cm mei “Nagasone Okisato Kotetsu Nyûdô” (長曽祢興里虎徹入道), nagasa 47.8 cm, sori 1.0 cm (please note that this blade was mirrored due to reasons of uniformity in depiction in this kantei series)

*

1.35 Mid-Edo period (1688-1781)

Here virtually the same applies as to the changes in long swords, that is, the Kanbun-shintô-sugata was given up in favor of an again more moderate sugata, the so-called Genroku-shintô-sugata. In other words, wakizashi curve more, show a harmonious taper, and end in a chû-kissaki. And this sugata was more or less kept unchangedly until kotô swords were revived in the late Edo period.

Picture 36: wakizashi from the mid-Edo period (from left to right): mei "Awataguchi Ômi no Kami Tadatsuna" (粟田口近江守忠綱), nagasa 51.8 cm, sori 1.8 cm mei "Sakakura Gonnoshin Terukane" (坂倉言之進照包) nagasa 58.3 cm, sori 1.4 cm

*

1.36 Late Edo to early Meiji period (1781-1876)

Sword production declined significantly with the transition to the 18th century but was on the one hand revived by Suishinshi Masahide and was on the other hand again stimulated by the turmoils of the bakumatsu era. Thus also wakizashi appear in larger numbers from around Tenpô (天保, 1830-1844) onwards. Again we see the same trend to large mid-Nanbokuchô shapes in the bakumatsu era but with a thicker kasane. As so many different wakizashi were made at that time, it is hard to name any representative school or smith for specific interpretations but famous is the Kiyomaro school for their magnificent short swords which are often modelled on shortened nagamaki blades.

Picture 37: various wakizashi interpretations from the late Edo and early Meiji period (from left to right): mei “Suishin-rōō Amahide + kaō” (水心老翁天秀), dated Bunsei two (文政, 1819), nagasa 45.4 cm, sori 1.2 cm mei “Minamoto Masayuki” (源正行), dated Kôka two (弘化, 1845), early name of Kiyomaro, nagasa 45.9 cm, sori 1.2 cm mei “Chôunsai Tsunatoshi” (長運斎綱俊), dated Tenpô eleven (天保, 1840), nagasa 46.2 cm, sori 1.0 cm mei “Ôshû Shirakawa-shin Tegarayama Masashige” (奥州白川臣手柄山正繁), dated Kansei ten (寛政, 1798), nagasa 45.8 cm, sori 1.0 cm

And last but not least, the well-known brief overview of the chronological changes in sugata:

Poll

Whilst doing the correction and revision of my Index of Japanese Swordsmiths, I arrive due to the larger font and the modified layout at a considerably larger number of pages, in concrete terms about 1,500 instead of the about 900 pages of the initial version. This raises the following question: Should I stick with two volumes, i.e. with the initial format of the index, what means a A-M and a N-Z volume but each now about 700 pages? Or should I instead go with three volumes each about 500 pages? At the same time, I am thinkin about adding some pictures, oshigata, signature details, or photos and photos of swordsmiths here and there where they might be useful supplements to the text. This in turn would mean in any case a three volume set as Lulu sets the limit of a single hardcover copy at 800 pages. In any case, I will try to set the price noticeably lower than the 280 USD (260 Euro) for the initial two volume set as the royalty/costs are far better at Lulu than at BoD where the initial set was print.

I can’t decide yet and want to start a poll to see where this might go. So if you have a second, please vote below. Thanks a lot!

And tomorrow I will post the last part of sugata-kantei before the Kantei series continues with jigane and jihada.

KANTEI 1 – SUGATA #7

Now we continue with the changes in the shapes of tantô and hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi, that means blades that come under the category of a dagger and not of a short sword like the later developed and noticeably longer shinogi-zukuri wakizashi.

*

1.23 Late Heian to early Kamakura period (1000~1232)

Tantô from before the early Kamakura period are exceptionally rare, so rare that they can be ruled out again for our kantei descriptions. This changes with entering the Kamakura period, although early Kamakura-period tantô are still very rare. Thus we are facing the same problem as with tachi, that is to say the lack of references which greatly limits our insight in shorter blades made at that time. Those few extant early Kamakura tantô are in hira-zukuri, show a little uchizori, have a rather full fukura, and measure mostly less than 24 cm. But it must be noted that there are also noticeably longer early Kamakura-period tantô extant. For example the Kyôto smith Awataguchi Hisakuni from whom we know a tantô with a nagasa of 29.1 cm and one with a nagasa of just 20.1 cm. Also it is safe to assume that also noticeable longer daggers were made throughout all these earlu times but which just did not survive as being merely weapons and utilitarian objects.

Representative schools and smiths for early Kamakura period tantô are: The Awataguchi (粟田口) school (Kunitomo [国友], Hisakuni [久国]).

Picture 19: tantô from the early Kamakura period (from left to right): mei “Hisakuni” (久国), nagasa 29.1 cm mei “Hisakuni” (久国), nagasa 20.1 cm

*

1.24 Mid-Kamakura period (1232-1288)

With the mid-Kamakura period, tantô level off at a standard length (jôsun, 常寸) of 25~26 cm, although of course also some shorter and longer blades were made which measure around 20 or 29 cm respectively. They are in hira-zukuri, have uchizori, and mihaba, fukura, and kasane appear at the jôsun interpretations in a highly harmonious manner. Because of this, the mid-Kamakura period is regarded as the time of bringing forth the most aesthetical tantô-sugata. But also some noticeably tapering tantô were made in the mid-Kamakura period and so classifying Kamakura-era tantô can be as difficult as classifying Kamakura-era tachi.

Representative schools and smiths for mid-Kamakura period tantô are: The Awataguchi (粟田口) school (Norikuni [則国], Kuniyoshi [国吉], Yoshimitsu [吉光]), Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊), the Shintôgo (新藤五) school (Kunimitsu [国光], Kunihiro [国弘]).

Picture 20: tantô from the mid-Kamakura period (from left to right): mei “Norikuni” (則国), nagasa 24.2 cm kokuhô, mei “Kunimitsu” (国光), Shintôgo, nagasa 22.4 cm mei “Rai Kunitoshi” (来国俊), nagasa 19.6 cm jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Yoshimitsu” (吉光), nagasa 27.3 cm

*

1.25 Late Kamakura and early Nanbokuchô period (1288-1336)

With the late Kamakura period it is as difficult as with the mid-Kamakura period, that means tantô maintain on the one hand the classic shapes, but grow on the other hand quite large. Accordingly there are tantô with a jôsun-nagasa, uchizori, and a very harmonious ratio of mihaba to nagasa, kasane, and fukura. Representative schools and smiths for these classic late Kamakura-period tantô are: The Rai (来) school (Kunimitsu [国光], Kunitsugu [国次]), Osafune Kagemitsu (長船景光), the Masamune (正宗) school (Yukimitsu [行光], Masamune [正宗]), Norishige (則重).

At the same time tantô with a nagasa of 27~32 cm, muzori or even a little sori, and a somewhat wider mihaba are seen. These were often made by Rai Kunimitsu (来国光), Rai Kunitsugu (来国次), the Hoshô (保昌) school, and Sadamune (貞宗) for example. And hira-zukuri tantô with a strikingly wide mihaba for their nagasa, the so-called Hôchô-style tantô (包丁, kitchen-knife tantô), were made among others by Masamune. Please note that Hôchô-style tantô were already made in the previous mid-Kamakura period, for example by Awataguchi Yoshimitsu.

Picture 21: tantô from the late Kamakura and early Nanbokuchô period (from left to right): meibutsu “Kuwana-Hoshô” (桑山保昌), mei “Takaichi-jû Kingo Fuji Sadayoshi”, dated Genkô four (元享, 1324), nagasa 25.8 cm meibutsu “Hyûga-Masamune” (日向正宗), nagasa 24.9 cm kokuhô, mei “Yukimitsu” (行光), nagasa 26.2 cm kokuhô, mei “Norishige” (則重), nagasa 24.8 cm

Picture 22: wider tantô from the late Kamakura and early Nanbokuchô period (from left to right): meibutsu “Hôchô-Masamune” (包丁正宗), nagasa 21.5 cm, sori 0.3 cm meibutsu “Tokuzen´in-Sadamune” (徳善院貞宗), nagasa 35.3 cm, sori 0.7 cm meibutsu “Ikeda-Sadamune” (池田貞宗), nagasa 30.9 cm, sori 0.5 cm jûyô-bijutsuhin, mei “Bishû Osafune-jû Kagemitsu” (備州長船住景光), dated Genkô three (元享, 1323), katakiriba-zukuri, nagasa 25.6 cm

Also relative many kanmuri-otoshi or unokubi-zukuri tantô with a thin kasane and muzori were made in the late Kamakura period, mainly by the Taima (当麻) school, Ryôkai (了戒), Ryôsai (良西), or Shikkake Norinaga (尻懸則長). And towards the very end of the Kamakura period certain smiths like Sadamune (貞宗), Takagi Sadamune (高木貞宗), Osafune Kagemitsu (長船景光), or Kanro Toshinaga (甘露俊長) started to make tantô in katakiriba-zukuri which can come without sori or with a very shallow sori.

Picture 23: tantô in kanmuri-otoshi-zukuri from the late Kamakura and early Nanbokuchô period (from left to right): mei “Ryôsai” (良西), nagasa 22.1 cm meibutsu “Akita-Ryôkai” (秋田了戒), mei “Ryôkai” (了戒), nagasa 27.2 cm meibutsu “Ikeda-Rai Kunimitsu” (池田来国光), mei “Rai Kunimitsu” (来国光), nagasa 26.3 cm

*

1.26 Mid-Nanbokuchô period (1336-1375)

When it comes to tantô, the mid-Nanbokuchô period brought the same trend towards oversized blades as it was the case for tachi. Please note that according to our present-day nomenclature, all “dagger” blades that measure over 1 shaku in nagasa are classified as wakizashi. Also the term sunnobi-tantô (寸延短刀) is in use to refer to refer to tantô which measure just a little bit more than 1 shaku. For oversized mid-Nanbokuchô period also the term Enbun-Jôji-sugata is in use which has the following features: Long nagasa of 30~40 cm, wider mihaba, full fukura, thin kasane, noticeable sakizori.

Representative schools and smiths for mid-Nanbokuchô tantô in Enbun-Jôji-sugata are: For Kyô-mono the Hasebe (長谷部) school (Kunishige [国重], Kuninobu [国信]) and the Nobukuni (信国) masters of that time; the next generation of Sôshû smiths (Hiromitsu [広光], Akihiro [秋広]); the Kanemitsu (兼光) school (Kanemitsu [兼光], Tomomitsu [倫光], Yoshimitsu [義光]); the Chû-Aoe (中青江) school (Tsugunao [次直], Tsuguyoshi [次吉]); Kinjû (金重), the Naoe-Shizu (直江志津) school (Kanetomo [兼友], Kanetsugu [兼次]).

Picture 24: tantô in Enbon-Jôji-sugata from the mid-Nanbokuchô period (from left to right): jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Sagami no Kuni-jûnin Hiromitsu” (相模国住人広光), dated Bunna five (文和, 1356), nagasa 32.1 cm, sori 0.4 cm mei “Kinjû” (金重), nagasa 29.7 cm, sori 0.3 cm jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Bitchû no Kuni Tsugunao saku” (備中国次直作), dated Enbun three (延文, 1358), nagasa 33.6 cm, sori 0.5 cm jūyō-bijutsuhin, mei “Kanetomo” (兼友), nagasa 28.1 cm, sori 0.3 cm

Parallel to the trend to extra large tantô or hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi, there were certain mid-Nanbokuchô smiths who remained faithful to more classic tantô shapes, for example Shizu Saburô Kaneuji (志津三郎兼氏), Osafune Chôgi (長義), Osafune Tomomitsu (倫光), or Ô-Sa (大左). Their tantô have a normal to just a little elongated nagasa, muzori or just a hint of a sori, and a moderate mihaba.

Picture 25: more classic tantô from the mid-Nanbokuchô period (from left to right): jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Kaneuji” (兼氏), nagasa 20 cm jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Chikushû-jû – Sa” (筑州住・左), nagasa 25.5 cm, sori 0.2 cm mei “Chikushû-jû – Sa” (筑州住・左) mei “Bishû Osafune Tomomitsu” (備州長船倫光), dated Kôan one (康安, 1361), nagasa 25.3 cm, sori 0,2 cm

*

1.27 Late Nanbokuchô to early Muromachi period (1375-1428)

Tantô and hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi did not stop growing towards the end of the Nanbokuchô and antering the Muromachi period. That means, the mid-Nanbokuchô period already brought rather large Enbun-Jôji-style dagger blades but with entering Muromachi times, the classical tantô decreases in number and the ko-wakizashi occasionally even reaches wakizashi lenghts. The sori is due to the length more noticeable and appears as sakizori but we observe that the wide mihaba of the previous period gradually disappears.

Representative schools and smiths for such long hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi are: The Ôei-Bizen (応永備前) school (Morimitsu [盛光], Yasumitsu [康光]) or the 3rd generation Nobukuni (信国). But we must bear in mind that most of these smiths made at the same time also still classical tantô with a nagasa of slightly less than 30 cm and muzori. Also kanmuri-otoshi-zukuri tantô were continuously made in the early Muromachi period and representative for such blades and for that time are: Tegai Kanezane (手掻包真) and the Niô (二王) school (Kiyonaga [清永], Kiyokage [清景]). Anyway, we learn that tantô generally decrease in number with entering the Muromachi period.

Picture 26: tantô from the late Nanbokuchô and early Muromachi period (from left to right): mei “Nobukuni” (信国), Ôei-Nobukuni, nagasa 23.5 cm mumei, attributed to Ôei-Nobukuni, nagasa 28.6 cm mei “Bishû Osafune Morimitsu” (備州長船盛光), dated Ôei 30 (応永, 1423), nagasa 26.8 cm mei “Bishû Osafune Morikage” (備州長船盛景), dated Eikyô seven (永享, 1435), nagasa 27.4 cm

*

1.28 Mid to late Muromachi period (1428-1572)

From the mid to the late Muromachi period we see how the wakizashi in general and the shinogi-zukuri wakizashi in particular gradually replaces the hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi but blades of the latter category were still made. They show a wide mihaba, no longer a thin but an appropriate kasane for the length, a full fukura, and a deep sakizori. Representative schools and smiths for hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi of that kind are: The Sue-Seki (末関) school (Kanefusa [兼房], Kanehisa [兼久], Kanemura [兼村]), Sengo Muramasa (千子村正), Tsunahiro (綱広), or Shimada Yoshisuke (島田義助).

In late Muromachi times, classic Kamakura-period tantô with a short nagasa of about 23~26 cm and with uchizori experienced a revival. Such blades were often made by the Sue-Seki (末関) school (Kanesada [兼定], Kanetsune [兼常]), Osafune Sukesada (長船祐定), Shimada Yoshisuke (島田義助), or Sue-Tegai Kanekiyo (末手掻包清).

Parallel to that a new tantô styles appears, the moroha-zukuri tantô, that has mostly a rather short nagasa of about 20~23 cm and a shallow sori and that was often made by the Sue-Bizen (末備前), the Sue-Seki (末関), and the Sue-Mihara (末三原) school.

Picture 27: different tantô styles from the mid to late Muromachi period (from left to right): jûyô-bijutsuhin, mei “Sôshû-jû Tsunahiro” (相州住綱広), 1st generation, nagasa 36.7 cm, sori 0.9 cm mei “Kanetsune” (兼常), around Eiroku (永禄, 1558-1570), nagasa 29.1 cm, sori 0.1 cm mei “Sukemune” (助宗), Shimada, nagasa 38.4 cm, sori 0.9 cm mei “Bishû Osafune Sukemitsu” (備州長船祐光), dated Bunmei ten (文明, 1478), nagasa 33.8 cm, sori 0.6 cm

Picture 28: moroha-zukuri tantô from the mid to late Muromachi period (from left to right): mei “Bishû Osafune Harumitsu” (備州長船春光), nagasa 18.75 cm mei “Bishû Osafune Tadayuki” (備州長船忠行), dated Bunmei three (文明, 1471), nagasa 17.7 cm

*

1.29 Momoyama to early Edo period (1572-1624)

The same way as the Enbun-Jôji-sugata was revived at that time for tachi, it was also revived for tantô. That means we see again longer hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi or sunnobi-tantô with a wide mihaba but this time with a sakizori (a remnant of the previous late Muromachi period), a fuller fukura, and a thicker kasane. Please note that most of these Momoyama to early Edo period blades are, due to their nagasa, today classified as wakizashi. But they were intended as copies of mid-Nanbokuchô blades where the classic wakizashi was yet not introduced.

Representative schools and smiths for a Momoyama period sugata or a Keichô-shintô-sugata are: Umetada Myôju (埋忠明寿); the Horikawa (堀川) school (Kunihiro [国弘], Kunimichi [国路], Kuniyasu [国安]); the Mishina (三品) school (Etchû no Kami Masatoshi [越中守正俊], Iga no Kami Kinmichi [伊賀守金道], Tanba no Kami Yoshimichi [丹波守吉道]); Echizen Yasutsugu (越前康継), Higo no Daijô Sadakuni (肥後大掾貞国), Hankei (繁慶), Nanki Shigekuni (南紀重国), Hizen Tadayoshi (忠吉), Kashû Kanewaka (加州兼若).

Parallel to that, some of the above mentioned smiths like Umetada Myôju, Horikawa Kunihiro, Horikawa Kuniyasu, Hizen Tadayoshi, Echizen Yasutsugu, or Higo no Daijô Sadakuni made also tantô in katakiriba-zukuri with a wide mihaba, a nagasa of about 30 cm, and either with a little sori or with uchizori.

Picture 29: tantô from the Momoyama to early Edo period (from left to right): jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Yamashiro no Kuni Nishijin-jûnin Umetada Myôju” (山城国西陣住人埋忠明寿), dated Keichô 13 (慶長, 1608), katakiriba-zukuri, nagasa 28.2 cm mei “Kuniyasu” (国安), Horikawa, ko-wakizashi in katakiriba-zukuri, nagasa 43.6 cm, sori 1.2 cm mei “Nisshû Furuya-jû Kunihiro saku” (日州古屋住国広作), dated Tenshô 14 (天正, 1586), nagasa 45.4 cm, sori 0.6 cm mei “Dewa no Daijô Fujiwara Kunimichi” (出羽大掾藤原国路), dated Keichô 20 (慶長, 1615), nagasa 31.7 cm, sori 0.7 cm

*

1.30 Early to late Edo period (1624-1781)

The production of tantô decreases significantly from the early Edo period onwards and those found are often copies of old kotô pieces, for example of the great early Sôshû masters like Masamune or Sadamune. And this means as mentioned in the last section that they show a longer nagasa and are therefore today classified as wakizashi. Occasionally tantô can be found from the following smiths: Kotetsu (虎徹), Mino no Kami Masatsune (美濃守政常), Harima no Kami Tadakuni (播磨守忠国), certain Hizen smiths, Ise no Daijô Tsunahiro (伊勢大掾綱広), and the later generations Yasutsugu (康継).

Picture 30: tantô from early Edo period (from left to right): mei “Ôsaka-jû Izumi no Kami Fujiwara Kunisada” (大坂住和泉守藤原国貞), made around Kan´ei 19~20 (寛永, 1642~43), nagasa 31.4 cm, sori 0.5 cm mei “Sôshû-jû Ise no Daijô Tsunahiro” (相州住伊勢大掾綱広), 5th generation, around Manji (万治, 1658-1661), nagasa 31.3 cm, sori 0.2 cm mei “[kikumon] Mishina Iga no Kami – Nihon-kaji-sôshô Fujiwara Kinmichi” (三品伊賀守・日本鍛冶宗匠藤原金道), 3rd generation, around Hôei (宝永, 1704-1711), nagasa 25.5 cm mei “Kashû-jû Kanewaka” (賀州住兼若), 2nd generation, around Meireki (明暦,1655-1658), nagasa 29.8 cm

*

1.31 Late Edo to early Meiji period (1781-1876)

The same Nanbokuchô revival as for long swords is seen at that time at tantô, i.e. hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi with a nagasa of 39~43 cm and a wide mihaba came again in fashion, although this time with a thicker kasane and with sakizori what distinguishes them from the “originals.” Representative smiths for these Enbun-Jôji revival blades are: Taikei Naotane (大慶直胤), Kiyomaro (清麿), Saitô Kiyondo (斎藤清人), Sa Yukihide (左行秀), Kurihara Nobuhide (栗原信秀), Hôki no Kami Masayoshi (伯耆守正幸), Oku Motohira (奥元平).

Many different dagger forms were taken up again in late shinshintô times, for example stout and thick yoroidôshi, ko-wakizashi in shôbu-zukuri, or osoraku-zukuri, kissaki-moroha-zukuri, and kanmuri-otoshi-zukuri blades. But we must not forget that still classic Kamakura-style tantô were made towards the end of the Edo period although with an important feature which most of the shinshintô-era tantô have in common, that is to say the somewhat thicker kasane.

Picture 31: different tantô styles from the late Edo to early Meiji period (from left to right): mei “Minamoto Hidetoshi” (源秀寿), early mei of Kiyomaro, dated Tenpô five (天保, 1834), nagasa 23.0 cm mei “Minamoto Kiyomaro” (源清麿), dated Kaei five (嘉永, 1852), nagasa 36.8 cm, sori 0.15 cm mei “Chikuzen no Kami Nobuhide” (筑前守信秀), nagasa 24.6 cm mei “Kiyondo saku” (清人作), dated Ansei seven (安政, 1860), nagasa 31.6 cm, sori 0.4 cm

Small Compendium

I was informed that a kind of small data base would be nice to go with your tablet that makes looking up certain things easier. Or in other words, a searchable eBook/PDF where you have things like characters used by swordsmiths, nengo, eto etc. in one place and don’t have to work with multiple files. With this, I created an extensive list of characters used by swordsmiths, sorted on the basis of stroke order, that comes with four different grades of simplification in writing for each characters, i.e. from standard printed style over two more hand-written styles to cursive script. This should give you more room to compare, and a greater headache of course due to the increased possibilities when it comes to cursive script 🙂

Also I added an eto list where you can look up which years are possible when a smith just added for example kanoto-ushi and no specific year. And in addition, I added all the poetic and other names of the lunar months which I was able find and a little more.

Most of the information in this compendium is of course found in several versions elsewhere but this is as mentioned before just to have that all in one file. So this is going to be for free and you can download the eBook/PDF below. For those who want that as a real book, I added a plain spiral bound version to Lulu that you can order for just printing and shipping (i.e. not going to add any royalties to that of course). But you are always free to make a little donation to this blog (see link at the very bottom) if you find this file or other articles of mine useful 😉 And by the way, my Easter eBook Super Sale is going to end tomorrow Monday. So last chance to grab a copy as there will be no more sale until Christmas (Lulu is not going to issue promo codes for eBooks, this is only done manually be me, so no sense in waiting for such a code).

Thank you and probably tomorrow I will continue with the Kantei series (two more articles until the topic sugata is finished).

*

Index Of Japanese Swordsmiths – Revision

Some of you might remember the lengthy discussion we had on NMB on a revised hardcover edition of my 2012 published two volume INDEX OF Japanese SWORDSMITHS.

Well, it never worked out and the initial hardcover version never worked to be easy buyable from everywhere in the world. Also an errata and a correction of all the typos seemed to be overdue and so I decided to give it another try as a two volume hardcover copy on Lulu. With this, we don’t have to care about a minimum number of buyers to get the thing started as it is print on demand. Also the price of the set will be noticeable lower as Lulu has way better royalties than BoD.

Now doing so, I will slightly change the layout o ensure a better legibility, coming along with a larger font as I got feedback that the initial font was way too small. I attach a preview who a page of the revised edition might look like.

And with this, you all come into play as I need some feedback to enlarge my own errata done over the three years. I have created an email address of its own for this, “swordsmith.errata@gmail.com”. This is a “fire-and-forget” email address, that means I will not reply from there and just collect your suggestions and corrections. If you really have to discuss a thing or to, please get in touch with me via my regular address “markus.sesko@gmail.com”.

Thank you all for your cooperation!

PS: The eBook version will be updated too of course.

Easter eBook Super Sale

Dear Readers,

Inspired by my last year’s Christmas Super Sale and responding to the”unfairness” that eBooks are always excluded from Lulu offers, I just started an Easter eBook Super Sale where ALL of my eBooks are reduced by 50%! This offer will be valid for a week so you have enough time to decide what you want. So fill up all your tablets (or PC´s) with all the important Nihonto and Tosogu reference material you need four your studies!

If you have any questions or can´t find the one or other book, don´t hesitate and contact me via my “markus.sesko@gmail.com.

Thank you and a Happy Easter to everyone!

http://www.lulu.com/spotlight/nihontobooks

PS: I have two signed Masamune paperbacks and a signed Tameshigiri hardcover here at my place. If you want one of them, please drop my a mail (price as announcted but free shipping).