A while ago I wrote in my article on the honorary titles of Mondo no Shô Masakiyo (主水正正清) and Shume no Kami Ippei Yasuyo (主馬首一平安代) about the sword forging contest initiated by the eighth Tokugawa-shôgun Yoshimune (徳川吉宗, 1684-1751). As mentioned therein, there were four winners selected, namely apart from Masakiyo and Yasuyo the 4th generation Nanki Shigekuni (南紀重国) and the Chikuzen smith Nobukuni Shigekane (信国重包). I also wrote that after the contest, the winners were supported by a program of orders and recommendations. But how did this „programm“ look like? To understand this, I want to introduce a concrete and very good example of an order directly from Tokugawa Yoshimune. In picture 1 we see a wakizashi with a nagasa of 58,8 cm (1 shaku 9 sun 4 bu) and a sori of 1,8 cm. It shows an itame mixed with mokume, ji-nie, plentiful of chikei and a midare-utsuri. The hamon is a rather small-dimensioned gunome mixed with chôji with more ups and downs along the monouchi and base than in between where the ha tends to suguha-chô with gunome-ashi. The nioiguchi is rather wide, quite ko-nie-loaden, and shows along the upper half sunagashi. The bôshi is sugu with a bit ko-midare and runs back in a ko-maru-kaeri with hakikake. The tang bears the single leaf of the Tokugawa aoi crest granted to the winners of the contest, and the detailed mei reads: „Chikushû-jû Nobukuni Minamoto Shigekane“ (筑刕住信国源重包) – „Uyauyashiku taimei o hôjite Tôbu ni itari kore o tsukuru“ (恭奉台命至于東武作之) – „Toki Kyôhô kanoto-ushi haru sangatsu“ (旹享保辛丑春三月). Translated: „Made by Nobukuni Minamoto Shigekane from Chikuzen province in the third month, spring, of the year of the ox of the Kyôhô period (1721), in Tôbu (= Edo) by respectfully following the shôgun´s order.“

Picture 1: wakizashi of Nobukuni Shigekane

Particularly striking on this blade are the horimono. We see on the ura side a kurikara-ryû as ukibori relief in a hitsu, and on the omote side the deity Fudô-Myôô, also in a hitsu. And at a Fudô-Myôô horimono on a Shigekane blade, you should prick up your ears. There is namely an interesting entry in the local history „Chikuzen no Kuni zoku-fudoki-furoku“ (筑前国続風土記附録) compiled in the Kansei era (寛政, 1789-1801) on behalf of the local Fukuoka fief (福岡藩) for which Nobukuni Shigekane had worked. The entry goes as follows: „Nobukuni Shigekane, first name Sukezaemon (助左衛門), called himself later Sukeroku Masakane (助六正包), Made in the Kyôhô era on orders of the shôgun Yoshimune at his Hama-goten (浜御殿) residence in Edo copies of the Wakasa-Masamune (若狭正宗) and Fudô-Kuniyuki (不動国行). As a reward, he got the – not hereditary – permission to engrave one leaf of the aoi crest under the habaki area. Due to this honor of the sovereign, his salary by the fief was raised to 15 koku and a support for five persons. This raised him about to the level of a lower ranking samurai.“ And indeed, the meibutsu Fudô-Kuniyuki showed the very same horimono at the base so we are able to can confirm this transmission through this wakizashi.

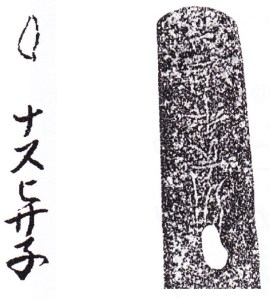

Let me introduce what we know about the Fudô-Kuniyuki (the sword also appears briefly in my Legends and Stories around the Japanese Sword 2). It was once a heirloom of the Ashikaga family but captured by Matsunaga Hisahide (松永久秀, 1510-1577) in the course of the defeat of the then shôgun Ashikaga Yoshiteru (足利義輝, 1536-1565). Hisahide presented it to Oda Nobunaga when on the occasion of his marching-in in Kyôto. After Nobunaga´s death it came into the possession of Akechi Mitsuhide (明智光秀, 1528-1582) who in turn presented it to his retainer Akechi Hidemitsu (明智秀満, 1536-1582). We know that Hideyoshi was eager to take revenge for Nobunaga´s death in order to come into power and when Hidemitsu realized that he was going to die, he volunatrily handed-over the Fudô-Kuniyuki to Hideyoshi so that the famous sword will not be destroyed. After the Battle of Komaki and Nagakute, Hideyoshi presented the sword to Ieyasu and so it came to be a heirloom of the Tokugawa family. However, it was damaged in the Great Meireki Fire in 1653 and had to be retempered by the 3rd generation Echizen Yasutsugu (越前康継). The Yasutsugu by the way were quasi the first-choice of the Tokugawa when it came to retemper precious meibutsu. As a sidenote, there exists the transmission that the horimono of Fudô-Myôô in flames caused the destruction of the sword by fire. Or to be more precise, it was rumored that the blade was tired of the peaceful times and committed quasi suicide by surrendering itself to the flames. However, the Tokugawa sold the sword in the early years of the Shôwa era and it was designated as jûyô-bijutsuhin even if it had a saiha. Unfortunately, the Fudô-Kuniyuki is missing since after World War II. All we have are some depictions, like for example in the „Kôtoku-katana-ezu“ (光徳刀絵図, picture 2), which in turn was at least made before the blade was damaged by fire. But as so often the case, we have different measurements in all these sources. The „Kôtoku-katana-ezu“ lists the Fudô-Kuniyuki with a nagasa of 1 shaku 9 sun 1 bu (57,9 cm) whereas the „Kyôhô-meibutsu-chô“ lists it with 1 shaku 9 sun 9 bu (60,3 cm), and a „Kiya-oshigata“ (木屋押形) copy from Kyôhô six (1721) with 1 shaku 9 sun 4 bu (58,8 cm). That means the copy of Shigekane follows ecactly the latter source.

Picture 2: The Fudô-Kuniyuki as depicted in the „Kôtoku-katana-ezu“.

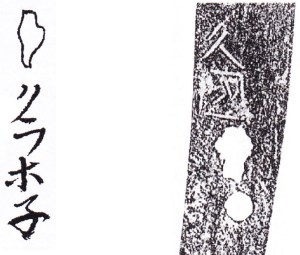

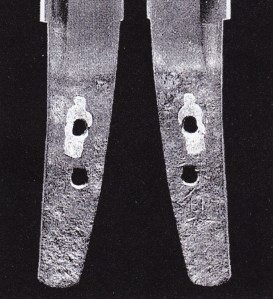

So Shigekane had no chance to see the original hamon of the meibutsu and so he focused merely on copying exactly the bôhi with its tsurebi and of course the horimono (see comparison pictures below). But with some imagination, we can see a similarity of the Shigekane-utsushi and the drawing in the „Kôtoku-katana-ezu“ in terms of the smallish togari protrusions connected by suguha sections in the monouchi area of the omote side. This blade gives us an insight of how sensitive the then sword world was, at least in higher circles. That means Tokugawa Yoshimune and higher ranking daimyô did not just order any old sword from the winners of the contest which was then stored away forever in a locker. Much attention was namely paid to details, everyone was talking about the swords of the „Kyôhô-meibutsu-chô“, and famous swords were taken out of the treasury and handed over to the smiths when they were in Edo so that they were able to study them hands-on. So it was a great honour for Shigekane to work on a copy of the Fudô-Kuniyuki and the details below show how thorough his approach was.

Picture 3: Comparison of the horimono. Please also not how the tsurebi of the ura side ends in the same way a bit lower than the hitsu for the kurikara-ryû.

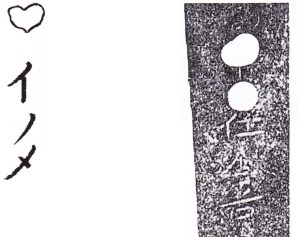

Picture 4: Comparison of the hi at the kissaki area and the hamon along the monouchi.