A few weeks ago, we have ended the basics when it comes to the sugata of a Japanese sword, that means the names and characteristics of the different elements of a blade. Now and over the next few chapters, I want to introduce on a chronological basis the differences in blade shapes, or in other words, doing the actual sugata-kantei.

*

1.8 Heian period (794-1184)

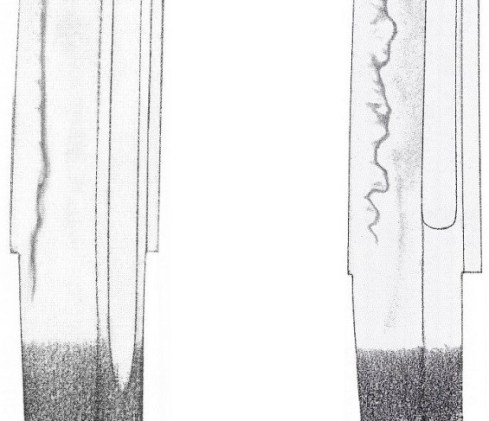

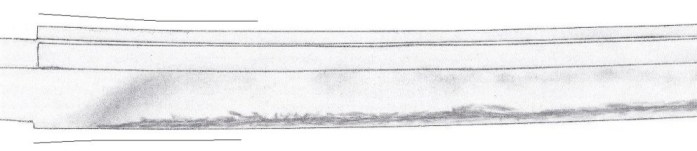

The Japanese sword got its curvature somewhere around the mid-Heian period, i.e. around the 9th and 10th century BC. As these earliest nihontô are an utmost rarity and virtually to impossible to handle and find on the market, they shall be ruled out for our considerations on sugata. So we start with the earliest “tangible” time what is the late Heian period, i.e. the 11th and 12th centuries. It goes without saying that even from those times it is very rare to study and purchase blades in their original condition as most of them either hold a status like kokuhô or jûyô-bunkazai and are thus only accessible in Japan and at special occasions, or were shortened and/or are polished down. What makes now a typical late Heian-period sugata? Blades from that time are slender, taper noticeably, have a deep koshizori, funbari, and a ko-kissaki, an interpretation which makes them look highly elegant, noble, or graceful, depending on what term you want to use to classify such a shape. In Japanese you will find terms and formulations like yasashii (優しい), yûbi (優美), yûga (優雅), kôshô (高尚), koten-teki (古典的), or hinkaku ga takai (品格が高い) to refer to a classic late-Heian period sugata. Another Japanese term which might be found in preferrably older publications is in no tachi (陰の太刀). It means “slender tachi,” or “unobtrusive tachi” if you want, but has to be understood as the opposite of the yô no tachi (陽の太刀), the “magnificent” or “powerful tachi,” as here the yin and yang (Japanese in and yô) terminology was used to distinguish between two fundamentally different tachi shapes. In late-Heian times, the classical tachi was the weapon of higher-ranking bushi and was thus wielded from horseback. Accordingly, unshortened blades from that time have a somewhat longer nagasa of about 80 to 85 cm. Again, I don’t want to go too much into historic details in this series on kantei so please forgive me for the lack of differentation here and there.

Let us stay with the sori for a while. I have mentioned that blades from that time show mostly a koshizori, that means the center of the curvature is towards the base, often right at the area of the habaki. But not only that, we can also observe that the curvature continues into the tang, i.e. also the nakago curves gently. An additional way to describe a koshizori which is relative often found in Japanese sources and which had been mentioned above is to say that the sori “bends down” towards the tip, saki ni itte fusaru (先に行って伏さる) or saki ni itte utsumuku (先に行って俯く). This just means that the sori does not increase again as it would be the case at a toriizori but runs out gently from the deepest curvature, the base, towards the tip.

Representative schools and smiths for a classic late-Heian period sugata are: Early Kyô-mono like the Sanjô (三条) school (Munechika [宗近], Yoshiie [吉家], Arikuni [有国], Arinari [有成]), Gojô (五条) school (Kanenaga [兼永], Kuninaga [国永]), or Awataguchi (粟田口) school (Kuniie [国家], Kunitomo [国友]); for Yamato the early Senju´in (千手院) school (Yukinobu [行信], Yukiyoshi [行吉]); the Ko-Bizen (古備前) school (Tomonari [友成], Masatsune [正恒], Takahira [高平], Kanehira [包平], Sukenari [介成], Sukehira [助平]); the Ko-Aoe (古青江) school (Yasutsugu [安次], Moritsugu [守次], Masatsune [正恒]); the Ko-Hôki (古伯耆) school (Yasutsuna [安綱], Ôhara Sanemori [大原真守], Moritsuna [守綱]); early northern Ôshû-mono like the Môgusa (舞草) school (Yasufusa [安房], Takeyasu [雄安], Morifusa [森房], Arimasa [有正]); the Ko-Kyûshû smiths like Sô Sadahide (僧定秀), , Chôen (長円), Ryôsai (良西); and the Ko-Naminohira (古波平) school (Masakuni [正国], Yukiyasu [行安], Yukimasa [行正]).

But it has to be mentioned that even if all these smiths are dated to the late or end of Heian period, we can see certain differences when it comes to their sugata. In other words, not all of these smiths focused solely on slender classic late-Heian period tachi shapes. For example Ko-Hôki Yasutsuna was known for making somewhat more robust and wider blades. And an extreme example is the Kyûshû Chikugo smith Miike “Tenta” Mitsuyo (三池典太光世) who made noticeably stout tachi for his time. These differences in shape might go back to the different production sites and the different clientel but what must not be forgotten is that we hardly have any reliable dates when it comes to such early smiths. For example, old sword documents date Sanjô Munechika traditionally around Ei´en (永延, 987-989) but more recent and comparative studies suggest that he was rather active at least a century later. The same applies to Yasutsuna who is listed as being active around Daidō (大同, 806-810) or Kōnin (弘仁, 810-824), eras when the Japanese sword was still in its uncurved chokutô phase. Or Miike Tenta Mitsuyo who is listed, depending on the source, around Kōhei (康平, 1058-1065), Jōhō (承保, 1074-1077), or Heiji (平治, 1159-1160).

In the following I would like to introduce pictures of blades from that time. Please take your time and internalize their elegance and gracefulness and also take a look at the nagasa. Although chances to handle blades like these in their original condition are as mentioned very rare, you will recognize them when holding a noticeable long but slender, elegantly curved blade with quite a smallish kissaki in hand. That means, with such a blade you know that you might be in the realm of the late Heian period or that you are facing a later work that tries to reproduce such a very classical sword. And in the latter case, i.e. when just the sugata suggests late Heian but everything else shintô or shinshintô for example, you might be able narrow down the kantei via remembering who was known in this or that time for making copies of very classical blades. But I will point out such “peculiarities” in the chapters on the schools and smiths.

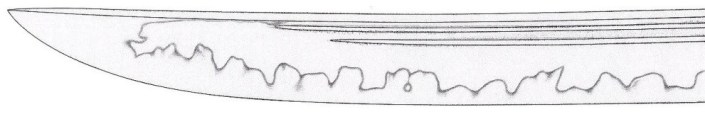

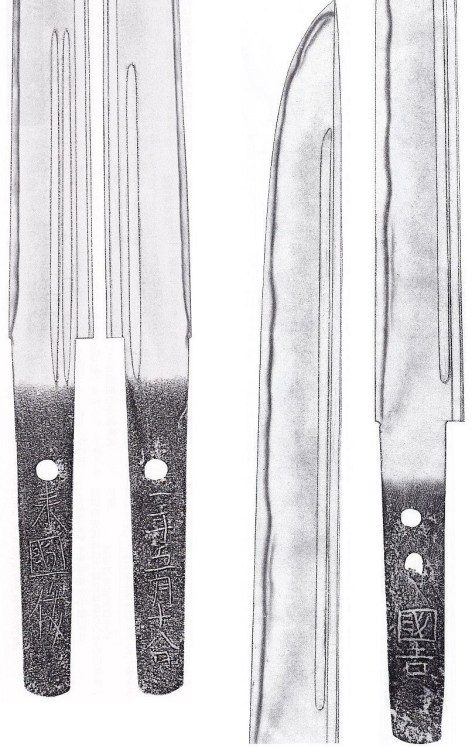

Picture 1: late-Heian period tachi (from left to right): meibutsu Mikazuki-Munechika (三日月宗近), mei “Sanjô” (三条), nagasa 80.0 cm, sori 2.7 cm meibutsu Tsurumaru-Kuninaga (鶴丸国永), mei “Kuninaga” (国永), nagasa 78.8 cm, sori 2.7 cm jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Aritsuna” (有綱), Ko-Hôki, nagasa 83.4 cm, sori 3.2 cm jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Yukiyasu” (行安), Ko-Naminohira, nagasa 73.9 cm, sori 2.7 cm

Picture 2: late-Heian period tachi (from left to right): kokuho, mei “Tomonari saku” (友成作), nagasa 80.0 cm, sori 2.9 cm kokuhô, mei “Sanetsune” (真恒), Ko-Bizen, nagasa 89.7 cm, sori 3.7 cm meibutsu Dôjigiri-Yasutsuna (童子切安綱), mei “Yasutsuna” (安綱), nagasa 80.0 cm, sori 2.7 cm kokuhô, mei “Sanemori tsukuru” (真守造), Ko-Hôki, nagasa 76.7 cm, sori 1.9 cm

Picture 3: atypical late-Heian period tachi (from left to right): meibutsu Ô-Kanehira (大包平), mei “Bizen no Kuni Kanehira saku” (備前国包平作), nagasa 89.2 cm, sori 3.4 cm meibutsu Ôtenta-Mitsuyo (大典太光世), mei “Mitsuyo saku” (光世作), nagasa 66.1 cm, sori 2.7 cm meibutsu Sohaya no tsurugi (ソハヤノツルキ), mei “Myōjun-denji sohaya no tsurugi - utsusu-nari” (妙純傅持ソハヤノツルキ・ウツスナリ), attributed to Miike Tenta Mitsuyo, nagasa 67.9 cm, sori 2.4 cm

*

1.9 Early Kamakura period (1185-1232)

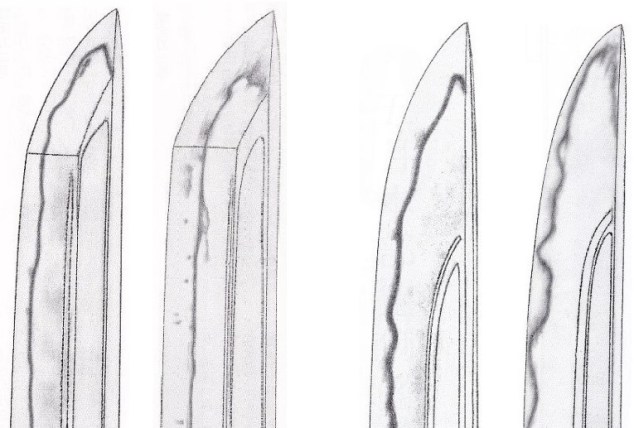

The general sugata did not change drastically or suddenly with the transition from the Heian to the Kamakura period but what we can observe is a slight increase in width and kissaki size and a little lesser tapering. The pronounced koshizori remains and the changes in shape reflect about the changes in time: The warrior class had just gained supremacy but the aristocracy was still strong, to put it in a nutshell. So these early Kamakura shapes are often described with wordings like “elegant but strong,” in Japanese yûbi de chikarazuyoi (優美で力強い) or yûsô (優壮), but often they are still referred to as “classic” (koten-teki, 古典的).

Representative schools and smiths for a classic early Kamakura period sugata are: Kyô-mono like the Awataguchi (粟田口) school (Kunitomo [国友], Hisakuni [久国], Kuniyasu [国安], Kunikiyo [国清]); the Ko-Ichimonji (古一文字) as connecting link from the Ko-Bizen to the Fukuoka and other Ichimonji schools (Norimune [則宗], Sukemune [助宗], Nobufusa [延房], Muneyoshi [宗吉], Nobukane [信包], Narimune [成宗], Sukeshige [助茂]); the Ko-Aoe (古青江) school (Sadatsugu [貞次], Suketsugu [助次], Tsunetsugu [恒次], Masatsune [正恒], Yasutsugu [康次], Nobutsugu [延次]); subsequent Ko-Kyûshû and Ko-Naminohira smiths like Bungo Yukihira (豊後行平).

Picture 4: early Kamakura period tachi (from left to right): meibutsu Kitsunegasaki (狐ケ崎), mei “Tametsugu” (為次), Ko-Aoe, nagasa 78.8 cm, sori 3.3 cm kokuhô, mei “Bungo no Kuni Yukihira saku” (豊後国行平作), nagasa 80.1 cm, sori 2.8 cm jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Kiyotsuna” (清綱), Ko-Niô, nagasa 79.7 cm, sori 2.3 cm jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Hôju” (宝寿・寶壽), nagasa 74.8 cm, sori 3.7 cm

*

1.10 Mid-Kamakura period (1232-1288)

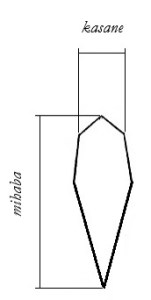

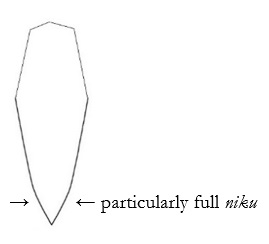

The increase in length and width continuously proceeded in the mid-Kamakura period and tachi became now noticeably more magnificent than their early-Kamakura or late-Heian predecessors. The mihaba gets wider, the tapering decreases, the sori shifts more from a koshizori to a toriizori, we can see plenty of hira-niku – and a variant of that, the hamaguriba – and the kissaki appears as a full chû-kissaki. But at about the same time, a blade shape appears which is even bigger, shows less taper, a somewhat thicker kasane and higher shinogi, a narrow shinogiji, and which ends in a stubby ikubi-kissaki. The mid-Kamakura period shape is mostly circumscribed as “magnificent,” or gôsô (豪壮) in Japanese.

Representative schools and smiths for a mid-Kamakura period sugata are: Kyô-mono like the Awataguchi (粟田口) school (Kuniyoshi [国吉], Kunitsuna [国綱], Yoshimitsu [吉光]); the Rai (来) school (Kuniyuki [国行], Niji Kunitoshi [二字国俊]); the Ayanokôji (綾小路) school (Sadatoshi [定利], Sadaie [定家]); for Yamato certain Senju´in-based smiths (Rikiô [力王], Sadashige [定重]); very early Sôshû smiths like Shintôgo Kunimitsu (新藤五国光), Shintôgo Kunihiro (国広), Daishinbô (大進坊); the Fukuoka-Ichimonji school (Yoshifusa [吉房], Sukezane [助真], Suketsuna [助綱], Norifusa [則房], Munetada [宗忠], Yoshimochi [吉用], Yoshimoto [吉元]); the Ko-Osafune (古長船) school (Mitsutada [光忠], Nagamitsu [長光], Junkei [順慶], Kagehide [景秀], Sanenaga [真長]); other Bizen-mono like Saburô Kunimune (三郎国宗) or Hatakeda Moriie (畠田守家); the Katayama-Ichimonji school (Norifusa [則房]); the Chû-Aoe (中青江) school (Suketsugu [助次], Shigetsugu [重次], Sadatsugu [貞次], Moritsugu [守次]); and the latest Ko-Kyûshû smiths like Sairen (西蓮) or Naminohira Yukiyasu (行安) or Yasuyuki (安行). And representative smiths for making tachi in the “other,” the massive ikubi-kissaki-style sugata were for example Niji-Kunitoshi, Osafune Mitsutada, or several Ichimonji smiths.

Before we continue with the Kamakura period it must be pointed out that classifying Kamakura-period sugata is not as easy as it seems. One problem is the pure lack of extant unshortened blades and another problem, which is connected to problem number one, is that basically only those blades are extant in an unaltered condition which were made by noted smiths for a high-ranking clientel. Also we have to distinguish between war swords (hyôjô no tachi, 兵仗太刀) and ceremonial swords (gijô no tachi, 儀仗太刀) and this differentiation is as important as the realization that we are facing just the tip of the iceberg. To visualize the complexity of these problems: Blades from that time can be made to be worn as ceremonial sword by courtiers (kuge), as war sword for courtiers (nodachi, 野太刀, not to be confused with the overlong field swords of the same name), as war sword of the military aristocracy (buke), as treasure sword for both buke or kuge, or as war sword for the common warriors. The blades of all these swords show more or less subtle differences according to their use. Though we have to recognize that all we have is a small window through which we can peek into the Kamakura-era sword world and we have to be careful when it comes to sugata from that time. To learn more about the difficulties when it comes to classifying Kamakura-period sword shapes, please read the blog post I wrote a while ago.

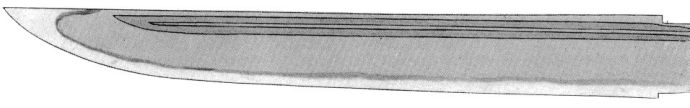

Picture 5: mid-Kamakura period tachi (from left to right): kokuhô, mei “Yoshihira” (吉平), nagasa 73.8 cm kokuhô, mei “Kunimune” (国宗), Bizen-Saburô, nagasa 72.7 cm, sori 2.4 cm jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Kuniyuki” (国行), Rai, nagasa 69.6 cm, sori 2.7 cm kokuhô, mei “Yoshifusa” (吉房), Ichimonji, nagasa 81.4 cm, sori 3.0 cm

*

1.11 Late Kamakura and early Nanbokuchô period (1288-1336)

Tachi continuously increase in size and length towards the end of the Kamakura and early Nanbokuchô period but what is now most conspicious is the increase in kissaki size and the giving-up of the koshizori in favor of a toriizori. Apart from that, the kasane starts to get thinner and the abundance of niku disappears again. Tachi-sugata from that time are large and magnificent but yet not exaggerated or strikingly oversized.

Representative schools and smiths for a late Kamakura to early Nanbokuchô period sugata are: Kyô-mono like the Rai (来) school (Kunimitsu [国光], Kunitsugu [国次], Mitsunake [光包], Ryôkai [了戒]); the Senju´in (千手院) school (Yoshihiro [義弘]), the Shikkake (尻懸) school (Norinaga [則長], Norihiro [則弘]); the Taima (当麻) school (Kuniyuki [国行], Kunikiyo [国清], Chô Aritoshi [長有俊]); the Hoshô (保昌) school (Sadamune [貞宗], Sadayoshi [貞吉]); the Tegai (手掻) school (Kanenaga [包永]); for the Sôshû tradition (Masamune [正宗], Yukimitsu [行光], Sadamune [貞宗], Shizu Saburô Kaneuji [志津三郎兼氏], Kinjû [金重], Gô Yoshihiro [郷義弘], Norishige [則重]); the Yoshioka-Ichimonji (吉岡一文字) school (Sukeyoshi [助吉], Sukemitsu [助光], Sukeyoshi [助義], Sukeshige [助茂]); the Iwato or Shôchû-Ichimonji (岩戸・正中一文字) school (Yoshiuji [吉氏], Yoshimori [吉守]); the Osafune school (Kagemitsu [景光], Chikakage [近景], 1st generation Kanemitsu [兼光]); the Hatakeda (畠田) school (Sanemori [真守], Morishige [守重]); the Un (雲類) group (Unshô [雲生], Unji [雲次]); other Bizen smiths like Kokubunji Sukekuni (国分寺助国) or Wake no Shô Shigesuke (和気庄重助); the Chû-Aoe school (Yoshitsugu [吉次], Tsuguyoshi [次吉], Nobutsugu [信次], Naotsugu [直次], Hidetsugu [秀次]); the Katayama-Ichimonji school (Sanetoshi [真利], Tsugunao [次直], Chikatsugu [近次]); and for Kyûshû for example Jitsu´a (実阿), Ô-Sa (大左), Sa Kunihiro (左国弘), the Enju (延寿) school (Kunisuke [国資], Kuninobu [国信], Kunitoki [国時], Kuniyoshi [国吉], Kuniyasu [国泰]), or for the Naminohira school Yasumitsu (安光).

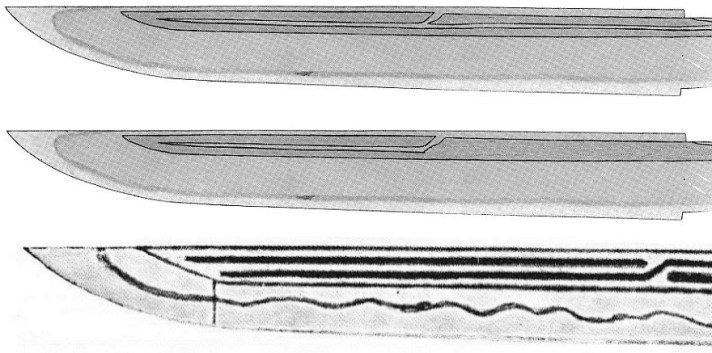

Picture 6: late Kamakura early Nanbokuchô period tachi (from left to right): jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Kunitoshi” (国俊), Rai, nagasa 75.5 cm, sori 2.4 cm kokuhô, mei “Kunitoshi” (国俊), Rai, nagasa 72.2 cm, sori 2.3 cm jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Sahyôe no Jô Fujiwara Kunitomo” (左兵衛尉藤原国友), Enju, dated Shôchû one (正中, 1324), nagasa 89.1 cm, sori 3.9 cm kokuhô, mei “Bizen no Kuni Yoshioka-jû Sakon Shôgen Ki no Sukemitsu” (備前国吉岡住左近将監紀助光), dated Genkô two (元享, 1322), nagasa 82.1 cm, sori 3.6 cm

*

1.12 Mid-Nanbokuchô period (1336-1375)

The mid-Nanbokuchô period marked the height of the length and overall size growth of the tachi. Blades from that time measure up to 90 cm and even some longer ôdachi with a nagasa of 120 cm were produced in considerable numbers. There is not much taper, a scarce niku, a thin kasane, a narrow shinogi-ji, a shallow toriizori, and an ô-kissaki with not much fukura. The vast majority of these oversized tachi have been shortened but the large kissaki, the thin kasane, and the wide mihaba identifies them, with some experience, rather easy as mid-Nanbokuchô even if they show the same, about 70~75 cm measuring nagasa of a tachi or katana. Please note that sometimes and due to later polishings and alterations, an ô-kissaki is not that large and elongated as you might think. Or in other words, certain mid-Nanbokuchô tachi are described with having an ô-kissaki but which is in fact only slightly larger than a chû-kissaki. Mid-Nanbokuchô tachi-sugata are described as “magnificent” or “exaggerated,” and in Japanese we find terms like gôsô (剛壮) or yûdai (雄大). And as the climax of this trend in size growth was reached in the eras Enbun (延文, 1356-1361) and Jôji (貞治, 1362-1368), the term Enbun-Jôji-sugata (延文・貞治姿) has become established to refer to oversized mid-Nanbokuchô blades.

Representative schools and smiths for a mid-Nanbokuchô period sugata are: For Kyôto the Hasebe (長谷部) school (Kunishige [国重], Kuninobu [国信], Kunihira [国平]); the early Nobukuni (信国) smiths; the later Rai smiths (Tomokuni [倫国], Kunizane [国真]); Daruma Shigemitsu (達磨重光); for Yamato the Tegai (手掻) school (Kanetsugu [包次]); the Hoshô (保昌) school (Sadakiyo [貞清], Sadayuki [貞行]); for Sôshû masters like Hiromitsu (広光), Akihiro (秋広), and Hiromasa (広正); for Mino the Sôshû-influenced Naoe Shizu (直江志津) school (2nd generation Kaneuji [兼氏], Kanetsugu [兼次], Kanetomo [兼友], Kanenobu [兼信], 2nd generation Kinjû [金重], Kaneyuki [金行], Tametsugu [為継]); the Sôden-Bizen (相伝備前) school (2nd generation Kanemitsu [兼光], Tomomitsu [倫光], Masamitsu [政光], Motomitsu [基光], Yoshimitsu [義光], Motoshige [元重], Chôgi [長義], Yoshikage [義景]); the Ômiya (大宮) school (Morikage [盛景], Sukemori [助盛], Morokage [師景]); the Un (雲類) group (2nd generation Unji [雲次], Unjû [雲重]); the Chû-Aoe (中青江) school (Tsuguyoshi [次吉], Tsugunao [次直], Moritsugu [守次], later generations Sadatsugu [貞次]); the Ko-Mihara (古三原) school (Masaie [正家], Masahiro [正広], Masamitsu [正光]); the Uda (宇多) school (Kunimitsu [国光], Kunimune [国宗], Kunifusa [国房]); Kashû Sanekage (真景); the Sekishû-Naotsuna (石州直綱) school (Naotsuna [直綱], Sadatsuna [貞綱]); Hôjôji Kunimitsu (法城寺国光); the Niô (二王) school (Kiyotsuna [清綱], Kiyosada [清貞]); for Kyûshû the Sa (左) school (Yasuyoshi [安吉], Yoshisada [吉貞], Kunihiro [国弘], Hiroyuki [弘行],); Tosa Yoshimitsu (土佐吉光).

Also we must not forget that up to the mid-Nanbokuchô period there were some smiths who worked in two blade shapes, that is to say on the one hand in a tachi-sugata that followed the style of their times, and on the other hand in a classical slender tachi-sugata which remind of the late Heian or early Kamakura period. Representative for these “reminiscence of classic tachi-sugata” were Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊), Rai Kunimitsu (来国光), Ryôkai (了戒), for the Osafune school Nagamitsu (長光), Kagemitsu (景光), Sanenaga (真長), and the 1st generation Kanemitsu (兼光), Kanro Toshinaga (甘呂俊長), and certain Enju smiths like Kunimura (国村) or Kunitomo (国友).

Picture 7: mid-Nanbokuchô period tachi (from left to right): kokuhô, mei “Bishû Osafune Tomomitsu” (備州長船倫光), dated Jôji five (1366), nagasa 126.0 cm, sori 5.8 cm jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Bizen no Kuni Osafune-jû Yoshikage” (備前国長船住義景), suriage, nagasa 74.4 cm, sori 0.9 cm kokuhô, mei “Senju´in Nagayoshi” (千手院長吉), dated Jôji five (1336), nagasa 135.7 cm jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Kaneuji” (兼氏), suriage, nagasa 66.7 cm

*

1.13 Late Nanbokuchô and early Muromachi period (1375-1428)

The late Nanbokuchô period brought a turning away from the exaggerated mid-Nanbokuchô blade shapes. That means tachi still have a rather long nagasa and a shallow toriizori but the kasane increases a bit, the blades taper again, and the tip returns to a chû-kissaki. And towards the end of the Ôei era (応永, 1394-1428) we are back at classical Kamakura-period tachi but now interpreted with a hint of a sakizori and a somewhat shorter nagasa. Well, it is difficult to recognize this sakizori as it is really just a hint but at an ubu blade from that time, you might just “feel” a somewhat different toriizori, i.e. with its deepest point slightly more towards the tip than usual.

Representative schools and smiths for a late Nanbokuchô and early Muromachi period sugata are: For Kyô-mono the the Sanjô (三条) school (Yoshinori [吉則]), the later Nobukuni (信国) masters; for Bizen the Kozori (小反) and Yoshii (吉井) school and for early Muromachi the Ôei-Bizen (応永備前) school (Morimitsu [盛光], Yasumitsu [康光]); for Mino the Akasaka-Senju´in (赤坂千手院) school; the Fujishima (藤島) school; the Uda (宇多) school.

Picture 8: late Nanbokuchô and early Muromachi period tachi (from left to right): jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Bishû Osafune Morimitsu” (備州長船盛光), dated Ôei 23 (1416), nagasa 76.1 cm, sori 1.1 cm mei “Bishû Osafune Tsuguyuki” (備州長船次行), Kozori, suriage, nagasa 78.4 cm, sori 2.3 cm