Just a couple of weeks ago I was following a discussion on NMB but couldn’t find the time to participate, and when I was finishing the reformatting of the Keichô-shintô project the other day, this thread and the discussions we had on the topic of utsushimono at two of our NBTHK-EB meetings (in 2009 and in 2014) came back to my mind. So before I continue with the kantei series, I would take the liberty of forwarding my two cents on this topic.

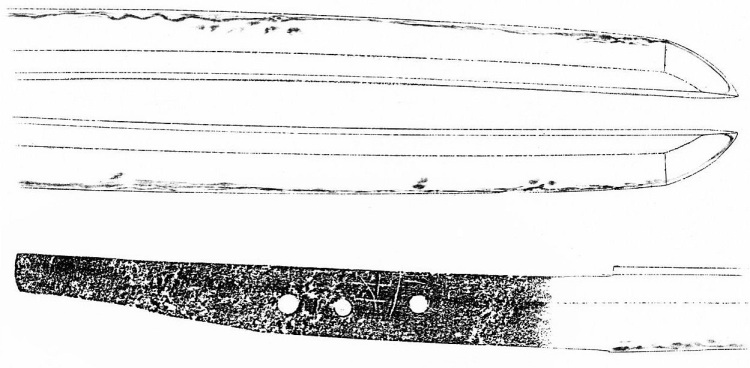

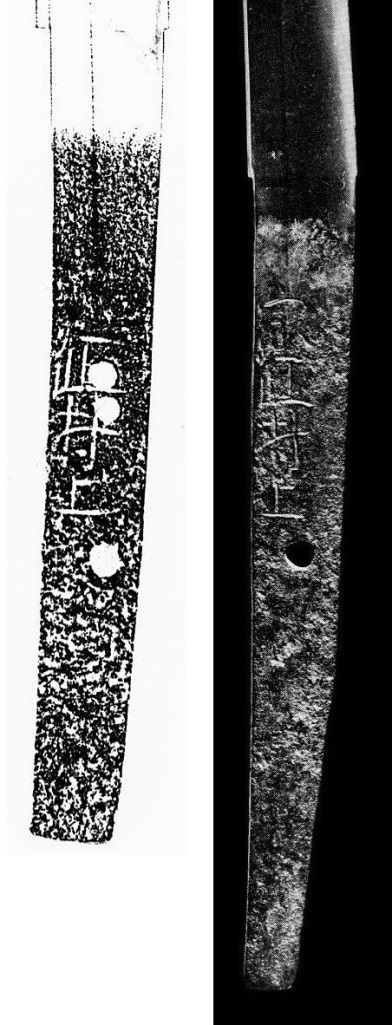

When talking about copies of blades, the term utsushimono (写し物) comes into play which means, well, “copy” but which can be used in a pretty broad sense. And that is the crux of the matter because when the term utsuhimono – or short utsushi (写し), e.g. as a suffix – is dropped, we need to differentiate. First of all, there is the “true copy,” that means a work that copies as faithfully as possible a concrete blade. For example the meibutsu Koryû-Kagemitsu (小竜景光) made by the Bizen smith Kagemitsu in the second year of Genkô (元享, 1322). Several smiths made copies of this blade, some of them on their own initiative but most because of being asked to do so by a customer. In my Tameshigiri book I introduced two Koryû-Kagemitsu-utsushi by the shinshintô smith Koyama Munetsugu (固山宗次). Interesting in this case is that Munetsugu made first, i.e. in Kôka four (弘化, 1847), a “reconstructed copy” of how the blade must have looked like initially (see picture 1 left). The Koryû-Kagemitsu has been shortened, although it still measures magnificent 80.6 cm in nagasa (see picture 1 center). Considerably later, i.e. in Bunkyû two (文久, 1862), Munetsugu made a 1:1 copy of the then condition of the meibutsu, and interesting this time, he also copied the signature of the original 1:1 and signed himself on the back of the tang (see picture 1 right). Please note that this does not come under the category of gimei as the smith added his name at least somewhere on the tang. But even if Munetsugu had not added his name on the back of the tang we would not see this blade as gimei. Meibutsu blades of the calibre of a Koryû-Kagemitsu can be compared to the Mona Lisa. So even if you make a perfect copy of the Mona Lisa, everybody knows that the original hangs in the Louvre and it is next to impossible to trick anyone buying it as original. Of course there were also schemes around meibutsu but they almost always evolved around a famous blade that was long believed to be lost but suddenly popped up somewhere, for sale of course. Details on the backgrounds of why and for whom Munetsugu made these copies can be found in my Tameshigiri book but it should be mentioned here that Munetsugu must have had the original in hand as the copy is indeed pretty close, that means much closer as you can make one just on the basis of oshigata drawings and plain measurements.

Picture 1: The Koryû-Kagemitsu and its two Koyama Munetsugu utsushi

I was already briefly talking about utsushimono in this post and like in the case above, the Fudô-Kuniyuki-utsushi of Nobukuni Shigekane (信国重包) can be considered as a “true copy.” That means even if the original meibutsu had to be retempered about 70 years before Shigekane got to work with it, his approach was still the attempt to copy as faithfully as possible a concrete blade. This brings us to the first “grey area.” Namely even supposing the Fudô-Kuniyuki had been missing at the time of Shigekane and all he had was good enough oshigata and descriptions, the result would still be considered as utsushimono as he copied, or tried to copy a concrete blade, although no longer existing. So the term utsushimono applies here too but it might not be paraphrased as “true copy.” In other words, the farther away the oshigata and descriptions from the original, the more we are entering the realms of a mere homage and eventually end up at a “free interpretation” of the Fudô-Kuniyuki if for example all that Shigekane had to work with was the order to “make me something like the famous but lost Rai blade” and the brief description that it had a this and that horimono and that it measured 1 shaku 9 sun 9 bu in nagasa. But of course also a smith (or his client) can specifically decide to make more like an homage, even if the original is still extant and could act as a model. An example for that are some of Echizen Yasutsugu’s (越前康継) copies of the meibutsu that were damaged by fire when Ôsaka Castle fell in 1615 and which he was ordered to retemper. So Yasutsugu made some “true copies” of these blades whilst he had the chance to study them hands on – or at least what was left of them in terms of steel, shape, and engravings – but he sometimes also copied just the sugata and horimono and added his own hamon. That means he did not even try to recreate the kind of hamon that the blades once might have shown. Again, they are still referred to as as utsushimono. By the way, I was talking about one of Yasutsugu’s “true copies” here.

Then there is the next category of “copies,” namely utsushi not of concrete blades but of styles of a smith or school. For example, if Koyama Munetsugu had made a blade that tries to reproduce the style of Kagemitsu, we would speak of a Kagemitsu-utsushi. Remember, the copy of the Koryû-Kagemitsu is not a Kagemitsu-utsushi but a Koryû-Kagemitsu-utushi. Many many blades were made over the centuries that try to copy the style of a certain school or master. I want to leave out the cultural backround but just one remark, it is common in East Asia for a craftsman to measure his own skill with that of a great master by trying to copy his works over and over again, not seldom over decades. Its just a learning and maturing process (artistically and spiritually) – learning through imitation – and does not mean that one uncreative. But lets get back to the topic. So if a smith tries for example to recreate a blade that is interpreted just like Osafune Kanemitsu (長船兼光) would have made a blade, it is referred to as Kanemitsu-utsushi, and if he tries to recreate a blade in the style of the Aoe School, it is referred to as Aoe-utsushi. And as borders between true copies and homages are fluid, there are other terms than utsushi or utsushimono which might nail the subtle differences better. For example nerau (狙う), “to aim at,” and narau (倣う・傚う), “to emulate, to imitate.” Incidentally, the term for learning, narau, has the same etymological origins (not going into detail on the sophisticated etymological differences of the characters for narau here). A little weaker form of saying “to aim at, to emulate, to imitate” is omowaseru (思わせる) which translates as “gives the impression of,” “has the appearance of” or “sth. reminds of sth.” For instance, a free interpretation that reminds of the style of Kanemitsu or of the Aoe School might be described as “Kanemitsu o omowaseru (兼光を思わせる)” or “Aoe-mono o omowaseru (青江物を思わせる)” respectively. It now depends on the writer, i.e. we see texts where such a free interpretation is still referred to as utsushi, but also such where it is stated that A tried to emulate B, that C aimed at D, and that a certain work reminds of X. So what its gonna be also depends on the context. Some smiths are known for focusing on concrete utsushi, for example Taikei Naotane (大慶直胤) who often copied or aimed at famous Osafune masters like Kanemitsu and Kagemitsu, whereas others rather reinterpreted certain things, for example Hankei (繁慶) and his working with the Sôshû tradition.

That brings us back to the different approaches of the smiths and it must be mentioned at this point that an utsushi is not considered as a forgery. Also forgeries try to reproduce a certain style, or even a concrete blade, as faithfully as possible, but they then “claim” to be a work of that school or smith or to be that very blade. In short, different intention. Or in other words, it doesn’t have to be by a great master or a very close copy but if the buyer/owner knows that the blade was made as copy of or as an homage to a certain school or smith, everything is fine. Like indicated above, it was very common to approach a smith and order a blade with the requirement it should be in the style of Kanemitsu or of the Rai School for example. Did myself so about ten years ago when I commissioned master Matsuba Kunimasa (松葉國正) with making me a naginata-naoshi style wakizashi that bases, freely, on a certain Ko-Aoe blade. What about the historic aspect? It is safe to assume that copies and forgeries coexisted from earliest times onwards. That means, learning through imitation was there what creates copies/imitations and making money from selling someone something cheap as something more valueable is is as human as it gets. So swords are of course no exception. It is hard to say for pre-Nanbokuchô smiths but one of the earliest examples of copying/imitating/recreating – isolated from the works left from the mere learning-through-imitation process – is the Ôei-Bizen group. When the turmoils of the Nanbokuchô period were over the Ashikaga family reinstalled the post of shôgun back in Kyôto and the upper warrior class was again trying to catch up with the cultural world of the aristocracy, after having tried something new and different, something more martial and bold in Kamakura. This is very well reflected in the sword fashions when the Bizen tradition, which was predominating during Kamakura times, was given up in the Nanbokuchô era in favor of the wild Sôshû tradition, which was given up again with the relocation of the bakufu to Kyôto in favor of the Bizen tradition. That means we see a significant backwards orientation at Ôei-Bizen as the group made blades in reminiscence of their great Kamakura predecessors. Another example for early utsushi are the numerous Rai or Yamashiro copies of the Sue-Seki smiths. My theory on the success of these copies is as follows: By that time, i.e. later Muromachi, sword forging in Yamashiro, that means Kyôto, was with entering the 1500s virtually non-existing and it is assumed that one reason for that was the massive “urban exodus” of the local smiths with the outbreak of the Ônin War. But unlike the changing fashions for long swords, classical koshigatana were always in demand. The koshigatana market had been predominated by the Yamashiro smiths as they equipped the warrior elite from the start with their fine daggers. Thus the peak of highest-quality tantô production is in the Kamakura period. The larger hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi that became increasingly in use with the Nanbokuchô period were a hint more utilitarian than the koshigatana, or at least more utilitarian than the “status symbol koshigatana” that were worn with formal costumes. So by the late Muromachi period, there were no Yamashiro masters at whom one could place an order for a classical koshigatana, i.e. a medium-sized tantô with harmonious proportions, a fine hada, and an elegant sugaha hamon. And thus warriors were approaching the then Seki masters who made them classical and high-quality koshigatana but which were much more affordable than looking for the real thing, i.e. trying to buy an Awataguchi or Rai original which always had been expensive. The Momoyama era experienced a “rediscovery” of the great early Sôshû masters and details on that like the upper warrior classes “need” for owning certain masters and the effect on then sword fashion can be found in my recent Masters of Keicho-Shinto and my Masamune book. But this much is to say: Sôshû was the order of the day and virtually every master or aspiring master was making Sôshû copies or a stab at the Sôshû tradition at that time.

And then came the shintô era of sword making which brought a lot of changes. The continuous peace, urbanization, accumulation of wealth for a higher number of individuals, and the conservative formation of an upper bourgeoisie had the effect that swordsmiths saw themselves more than ever as artists rather than as craftsmen. As a result, faithfully imitating certain predecessing masters or styles was no longer enough. Kotô blades are pretty much form follows function coupled with a special sense of aesthetics, i.e. simply put, the aesthetics of nativeness or natural simplicity. The great Ôsaka-shintô, Edo-shintô and early Hizen masters (just to name a few) developed with their strong creative power certain concepts, that means they started to separated the individual aesthetics of a blade like the sugata, jigane, hamon, and bôshi, just to rearrange them according to their overall idea of a sword blade. And utsushimono were no exception. Still “true copies” were made but we see more and more idealized reinterpretations of certain styles. In other words, these shintô masters reflected what constituted for example the Yamashiro tradition or for which the Yamashiro tradition was recognized for and banned these very elements onto canvas, in their case onto a sword blade. To stay with the example Yamashiro, the Yamashiro tradition is first of all famous for a densely forged, uniform jigane and a highly elegant suguha or suguha-chô. Accordingly, the great shintô masters focused on these elements and highlighted them at their own discretion. This changed again with shinshintô times as the shinshintô masters so to speak had to – after almost a decade of lean spell and a decrease in demand for swords and a decline craftsmanship – “reinvent” the whole wheel and were first of all aiming again at the kotô models. Rephrased, they first had to “learn” again through imitation before they were able to go over to free reinterpretations (which are by the way hardly seen in shinshintô anyway). Using the example of car makers and the Jaguar E-Type, the shinshintô masters were making as faithful as possible Jaguar E-Type retros whilst the shintô masters took everything for what that icon of a car stands for and created something new that might only remind of the original at a glance, or that can only be recognized as being Jaguar E-Type inspired when you have a decent undertanding of classic cars. But if the master was a great master, you can see what his inspiration was, how he skillfully highlighted certain elements, and how he really conveyed the aesthetics of the E-Type, oh pardon me, the Yamashiro tradition. But if a master was not that good, you might get what he was aiming at but the result is in the worst case a “Yamashiro grotesque.” Just like the thin line between an outstanding and a “too much” concept car.

Perfect timing, Aoi Art just put an interesting piece on sale. Link here (and picture below). It is a copy of a copy, that means Kasama Ikkansai Shigetsugu (笠間一貫斎繁継, 1886-1965) copied a blade by Taikei Naotane (大慶直胤, 1778-1857) which the latter had modelled, rather freely if you compare it to the three originals introduced in my Masamune book, on one of the Hôchô-Masamune. Like Koyama Munetsugu, Shigetsugu also copied the signature “Mo Hôchô-Masamune Naotane + kaô” (模包丁正宗直胤) of Naotane’s copy (or rather homage). Shigetsugu himself signed on the ura side, interestingly with “Ikkansai kore o tsukuru” (一貫斎造之), i.e. just with his gô and omitting his smith name (blade got papered to Shigetsugu by the way, so it is none of the other numerous Ikkansai smiths).

Leaving aside the art aspect, making a convincing and “true copy,” for example making a Koryû-Kagemitsu-utsushi, requires quite a high level of skill. Imagine how perfectly you have to master the craft to know how to arrange, fold, and forge your initial steel bundle and harden the blade to get in the end the exact same kinsuji at the exact same spot as on the original. You can do a lot with tsuchioki but in general, there are no tricks or shortcuts. That means you can’t “draw” a kinsuji onto a blade. It is just amazing how some smiths did this!