I would like to add a few introductory words before we start with the Sanjô school. First of all and speaking of the gokaden in my last post, the Japanese swordsmiths school are usually introduced via the aforementioned goki-shichidô system. That means even if the gokaden are so dominant when it comes to kotô times, the swordsmiths schools are usually not introduced in the gokaden order Yamashiro → Yamato → Bizen → Sôshû → Mino → Rest of the Sword World but, either starting with Yamashiro or Yamato, worked off province by province for each goki-shichidô entity. So Bizen comes way after Yamashiro and Yamato as the system first goes eastwards from the Kinai region, then north, and then quasi comes back and goes west and down to Kyûshû. You might imagine this system as a clock, with Kinai in its center and a shichidô circuit as its hand, starting with the Tôkaidô and working-off anti-clockwise the Tôsandô, Hokurikudô, San’indô, San’yôdô, Nankaidô, and Saikaidô, i.e. Kyûshû (see picture below). Well, some publications don’t stick strictly to this clock-system and might introduce the Hokurikudô schools before those along the Tôsandô but going anti-clockwise is how the order of school introduction basically works. Also there is no rule with which of the two major Kinai-based traditions, i.e. Yamashiro and Yamato, to start. Some use a chronological approach and say Yamato is the oldest tradition and start so with the Yamato schools but there is actually not that a big time difference between the emergence of the earliest Yamashiro (i.e. Kyôto-based) and Yamato (i.e. Nara-based) schools. The historical and geographical backgrounds for the development of each of the first indigeneous schools of sword making (e.g. Yamashiro, Yamato, Ko-Hôki, Môgusa, Ko-Kyûshû) are sophisticated topics on their own and should be omitted here. Anyway, like you already noticed, I want to start with Yamashiro. Oh, and a last note before we start: I will present the blades here for a better readbility of the posts and due to reasons of space in a horizontal manner. This was quite a difficult decision as I break away from the standard rule to present blades vertically to get an instant feel for the sugata and proportions but the blog posts will just become too lengthy and too confusing with all the scrolling. But everyone is free to download the pics and rotate them. I apologize for the extra work.

*

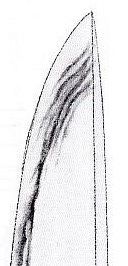

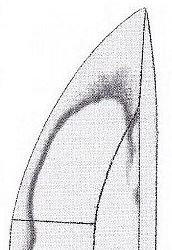

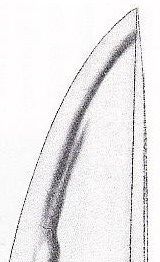

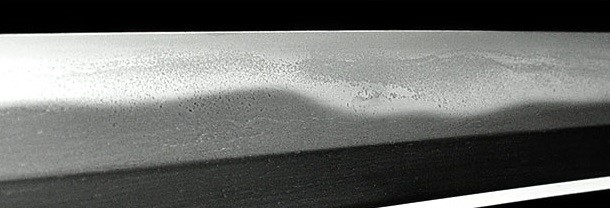

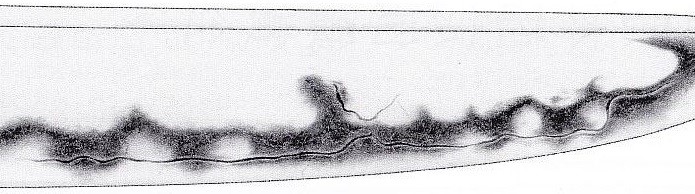

The Sanjô school was founded by Munechika (宗近), nickname Kokaji (小鍛冶), who is traditionally dated around Ei´en (永延, 987-989), what means he worked at about a time when Kyôto had been the new imperial capital for two centuries and roughly 250~300 years after the youngest swords in the Shôsô’in Repository had been made. So Munechika’s works are considered to be one the earliest extant specimen of a fully developed nihontô, what is a single-edged and curved blade in (as far as long swords are concerned) shinogi-zukuri, and standing in front of for example the meibutsu Mikazuki-Munechika (三日月宗近), it really looks its age (see picture 1). I say “standing in front of” on purpose because chances to study a Munechika hands on or come across one in the wild are virtually zero. All known blades are either in temple possession, imperial treasures (gyobutsu, 御物), or preserved in the Tôkyô National Museum. But the ancient, highly dignified, and graceful look of the Mikazuki-Munechika does not only go back to its age as for example Ko-Hôki and Ko-Bizen blades that date back to around the same time are so to speak more “substantial,” although being still pretty elegant at the same time. The highly dignified and graceful look of the Mikazuki-Munechika has to be seen in its contemporary cultural context as experts agree that it was most likely not made as a war sword. Of course it also has lost some substance due to the polishes that were necessary over ten! centuries but it never had been massive in the first place. At the time it was made, the good old Heian culture was at its peak. The famous Pillow Book and Tale of Genji were written when Munechika was active and the court was full of refined aristocrats for whom swords were merely symbols of their rank and obligatory accessories. Apart from one major disturbance, the rebellion led by Taira no Masakado (平将門) in 939/40, the imperial capital was quite peaceful up to the time of Munechika and although the first dark clouds were gathering over the aristocracy, there was yet no sign that the just briefly forming military class was ever becoming so strong that it takes over the entire country. It goes without saying that most of the then swordsmiths were indeed producing weapons but the largest customer base for Munechika and his contemporary Kyôto-based colleagues was the aristocracy. Accordingly and apart from the graceful sugata, a blade not only had to be masterly crafted but also had to be refined and beautiful as everything rural, rustic, and uncouth was usually frowned upon in noble circles. So Munechika’s blades show basically a soft looking and beautiful jigane with a fine ko-mokume in combination with a relative narrow suguha-based hamon that is hardened in ko-nie-deki. There are actually quite many hataraki like nijûba, sanjûba, uchinoke, ko-ashi, yô, yubashiri, kuichigaiba, muneyaki, inazuma, kinsuji, ji-nie, and chikei and the suguha is livened up by ko-midare and even subtle ko-chôji elements. Also the hada varies in density and shows here and there larger structures but all these hataraki and features are very natural, unaffected, and unsophisticated and put pointly, his blades make the overall impression of being works of one from a group of the earliest outstanding smiths that had just mastered their craft but for whom it was yet not time to experiment with forging and hardening techniques from an artistic point of view. Or in other words, Munechika would not even come up with the idea of hardening a flamboyant ôbusa-chôji even if he was probably technically capable of doing so. Munechika and his colleagues put on the clay coat how they knew it will work for the hardening process, maybe with some accentuations here and there, but the principal job in creating the hamon was left to the metallurgical – back then “magical” – interplay between steel and heat treatment. Incidentally, there is the tradition that Munechika was a court noble himself who started to forge swords as a pastime in his residence along Kyôto’s Sanjô. It turned out that he was very talented and soon took orders from his noble colleagues and even from the emperor, but just as it is the case with Masamune, there are so many legends and plays around Munechika that we do not longer know which tradition has a core of truth and which one is just pure fiction.

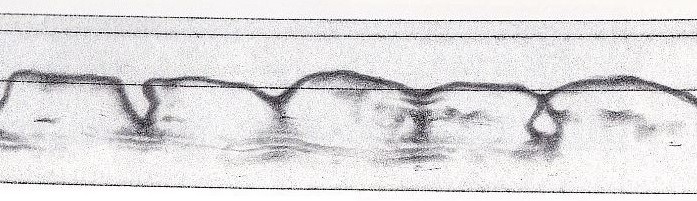

Picture 1: kokuhô, tachi, mei: Sanjô (三条), meibutsu Mikazuki-Munechika, nagasa 80.0 cm, sori 2.7 cm, motohaba 2.9 cm, sakihaba 1.4 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune [Tôkyô National Museum]

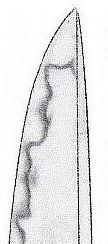

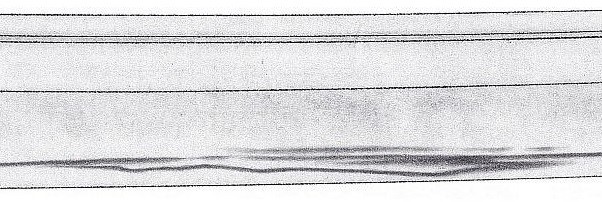

Picture 2: jûyô-bunkazai, tachi, mei: Mune… saku (宗◯作) (Den Munechika), nagasa 78.8 cm, sori 3.2 cm, motohaba 2.8 cm, sakihaba 1.5 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune [Wakasahiko-jinja, Fukui Prefecture]

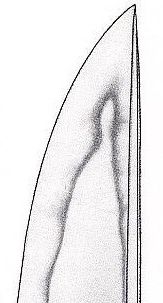

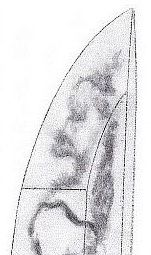

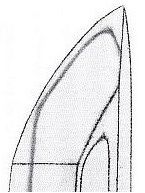

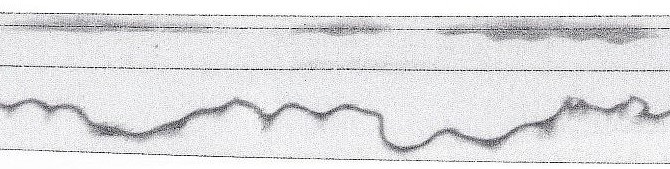

Picture 3: gyobutsu, tachi, mei: Munchika (宗近), nagasa 78.4 cm, sori 2.4 cm, motohaba 2.85 cm, sakihaba 1.5 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune [imperial treasure]

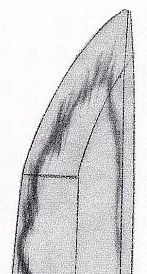

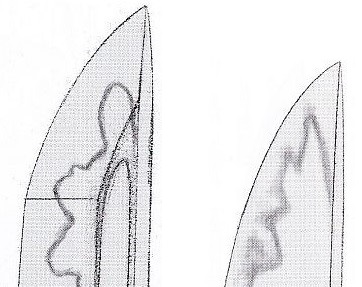

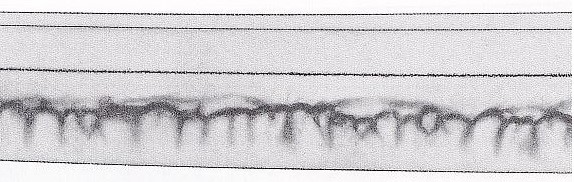

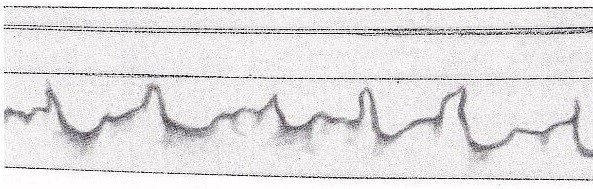

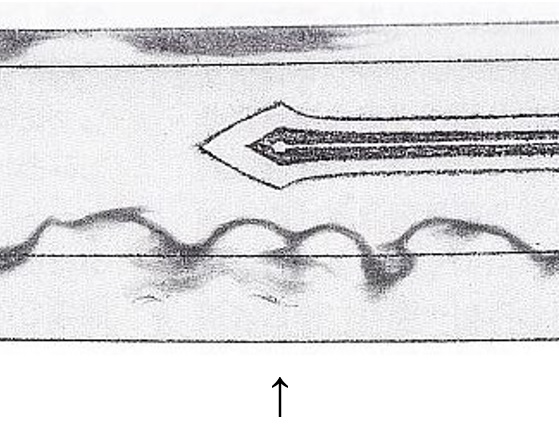

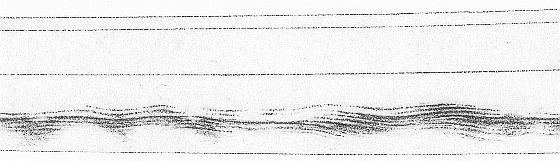

Picture 4: Characteristic features of Sanjô Munechika’s workmanship.

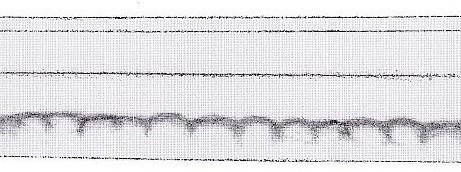

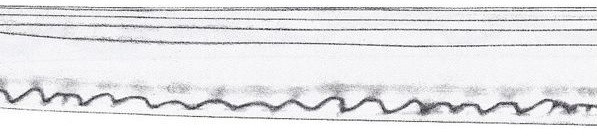

I have already described the characteristic features of Munechika’s workmanship above but want to point them out in detail in picture 4 on the basis of the oshigata introduced in picture 3. As you can see, there is a general trend towards more horizontal hataraki and towards a “multi-layered” hamon. Before we continue with other smiths of the Sanjô school, I want to deal with Munechika’s tang finish and signatures. The tangs of the Mikazuki-Munechika and of the gyobutsu are in kijimono-gata whereas the others are just tapering and slightly curved. Due to the age the yasurime are hardly discernible but some tangs of Munechika do show katte-sagari yasurime. If the tip of the tang is not chamfered as on the Mikazuki and the jûyô-bunkazai seen in picture 5, it is usually a shallow kurijiri. Munechika either signed with a fine and smallish chiselled niji-mei “Munechika” on the haki-omote, or with a somewhat larger dimensioned niji-mei “Sanjô” on the haki-ura side. (The jûyô-bunkazai seen in picture 2 was long thought to bear a niji-mei but traces of the character for “saku” can be seen between the top and the second, the ubu mekugi-ana. The later added upper mekugi-ana goes goes through the now no longer legible character for “chika.”) There is no definite answer so far that explains the question why he either signed with “Munechika” or “Sanjô” and why he switched between the haki-omote and haki-ura side. Also we will probably never able to tell for sure if there were two or even three generations with that name as some assume. Please note that there are actually many blades with the yoji-mei “Sanjô Munechika” going round but they are basically all ruled out as gimei. Well, and then there is the meibutsu Ebina-Kokaji on which I did a write-up a while ago here.

Picture 5: jûyô-bunkazai, tachi, mei: Sanjô (三条), nagasa 78.2 cm, sori 3.3 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune [Nangû-taisha, Gifu Prefecture]

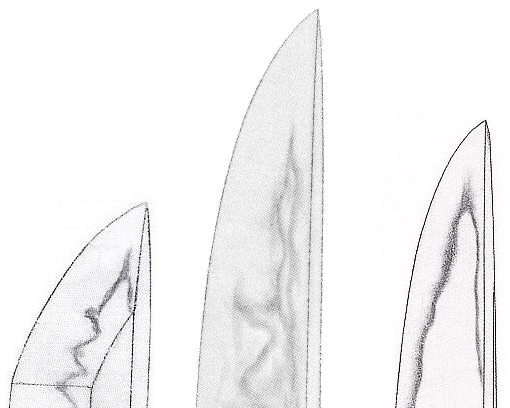

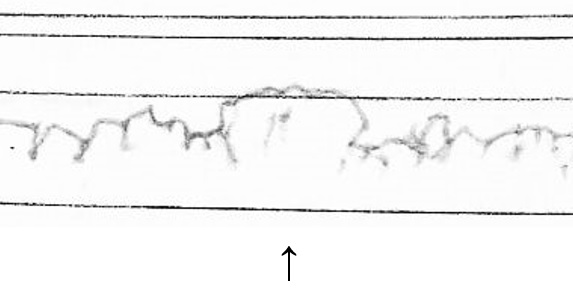

Picture 6: The signatures of Munechika. From left to right: Mikazuki-Munechika, jûyô-bunkazai of the Nangû-taisha, gyôbutsu, jûyô-bunkazai of the Wakasahiko-jinja

As this series is on kantei, I don’t want to just forward characteristics in workmanship and that’s it but in the case of these very early smiths it isn’t easy at all to give kantei tips as hardly any of their works are accessible anyway and as I so have to rely heavily on what is written in the references. Now Sanjô Munechika, Ko-Bizen Tomonari (古備前友成) and Ko-Hôki Yasutsuna (古備前友成) are often mentioned in the same breath when it comes to the founder generation of the nihontô that is known by name. First of all, Munechika’s and Tomonari’s workmanships are closer together than they are with the workmanship of Yasutsuna. Both Munechika and Tomonari forged a ko-mokume but that of Munechika is by trend somewhat finer whereas it stands more out at Tomonari. Also the ji-nie is more evenly distributed over the blade at Munechika than it is at Tomonari where we can also see some utsuri and jifu in turn. Yasutsuna then again mixed in some larger ô-hada structures and principally rather forged in itame than in ko-mokume. Also his ji-nie is more rough and visible than that of Munechika and Tomonari as his entire jiba is way more nie-laden than it is at the former two smiths. When it comes to the hamon, Tomonari’s ha tends more to nioi, i.e. the order goes Yasutsuna → Munechika → Tomonari in terms of the intensity of the nie. Munechika’s hamon appears with its majority of horizontal hataraki more “layered” whereas we see a hint more fully formed ko-chôji and ko-midare at Tomonari and not this “layer effect” and more sunagashi and hotsure at Yasutsuna which give his ha a somewhat more frayed appearance. Apart from that, Yasutsuna’s hamon usually starts with a prominent yaki-otoshi. But most obvious are the differences in sugata as Munechika’s blade are as mentioned very graceful and slender whereas those of Tomonari and Yasuchika are more magnificent and wide and show a way more pronounced koshizori than it is the case at Munechika.

*

In the next part I will continue with the sons and students of Munechika before we come to the Sanjô descendant, the Gojô school. I hope you like so far where this kantei series is going and the next post should follow in a little.