According to tradition, Ryôkai (了戒) was a very early son of grand master Rai Kunitoshi (来国俊), born when Kunitoshi was only 17 years old. He entered priesthood at an early age of 16, taking the very name Ryôkai, but returned later to secular life to forge swords, allegedly not only with his father but also learning from Ayanokôji Sadatoshi (綾小路定利). As always, there are several traditions and theories going round. One says that he was actually a Nara smith who came to Kyôto to study with Kunitoshi. Another one suggests that he started a normal career as a swordsmith and entered priesthood only later in life, whilst sources who follow the approach that Niji Kunitoshi and Rai Kunitoshi were different smiths say that Ryôkai was the son of the former and thus the brother of Rai Kunitoshi. Well, when we take a look at the extant date signatures of Ryôkai, which start from Shôô three (正応, 1290), followed by date signatures from Einin (永仁, 1293-1299) and Kagen (嘉元, 1303-1306) to Enkyô two (延慶, 1309) as the latest, we learn that he was active at about the same time when Kunitoshi signed in sanji-mei. We know that Kunitoshi was born in 1240. So when we follow the tradition that Ryôkai was born when Kunitoshi was 17 years old, we arrive at Kôgen two (康元, 1256) as year of birth for Ryôkai (or at Shôka one [正嘉, 1257] if we follow the Western way of counting years). This date (Kôgen two) is also forwarded by the Kotô Meizukushi Taizen by the way, what means that not all of its data is far-fetched. This in turn means that he was 34 when he made the earliest extant dated blade from Shôô three (1290) what sounds very plausible. The Kotô Meizukushi Taizen also says that Ryôkai died in Shôkyô four at the age of 72 but the Shôkyô era (正慶, 1332-1334) only lasted for two years, and apart from that, if you count 72 from Kôgen two (1256), you arrive at 1328 (or 1327 according to the Japanese way), what in turn would correspond to Karyaku three. Taking into consideration that Ryôkai’s known date signatures end noticeably before those of Kunitoshi (of whom we know date signature up to 1321), I tend to think that he might have died before his father and indeed in the Karyaku era (嘉暦, 1326-1329). Or in other words, the Kotô Meizukushi Taizen might be right about his age at death but not about the year he died in.

Before we come to the workmanship of Ryôkai, I want to elaborate on his standing in the sword world, or on his ranking if you want. There are 5 blades of him that made it jûyô-bunkazai (3 tachi, 1 tantô), no kokuhô, about 90 jûyô, and 2 that passed tokubetsu-jûyô. In comparison, Rai Kunitoshi has 4 kokuhô, 17 jûyô-bunkazai, more than 200 jûyô, and about 30 tokubetsu-jûyô. But we have to bear in mind that (due to the fact that Kunitoshi was the grand master of a bustling workshop) there are in total more blades of Rai Kunitoshi extant than of Ryôkai, so these numbers are relative. An interesting aspect of Ryôkai’s ranking is gained by looking into contemporary records. For example, the Chûshin Mono (注進物), a report on sharp swords from the entire country compiled on request of the bakufu in Shôwa two (正和, 1313) which contains the name of 60 smiths, does list Ryôkai but not his father Rai Kunitoshi. Well, the emphasis of such early works remains to be seen as for example, the Chûshin Mono lists for Yamashiro also Sanjô Kokaji Munechika, Awataguchi Kuniyoshi, Awataguchi Hisakuni, Ayanokôji Sadatoshi, and kiku-gyosaku, and therefore I tend to interpret sources like that as mere guidelines for what kind of swords are “appropriate” to be owned by (and presented to) the contemporary high-society rather than referring to their effective sharpness. But just due to the fact of being on this list, you can get an idea of how high Ryôkai’s blades were regarded these days.

*

Now to the workmanship of Ryôkai. In general, it can be said that the sugata and jiba of his works, and that means both tachi and tantô, are pretty close to Rai Kunitoshi. However, many of his tachi are more on the slender side, showing a noticeable taper, a deep sori, and a smallish kissaki, and it is assumed that it is this trend towards a more classical elegance might be the reason for why some assumed he studied with Ayanokôji Sadatoshi. But at Sadatoshi’s slender tachi, the koshizori is more pronounced and straightens more out towards the tip. Apart from that, some of Ryôkai’s tachi show a somewhat higher shinogi (and partially also a higher iori-mune) what in turn might have been the reason for assuming a Yamato origin. This is further substantiated by the fact that Ryôkai’s jigane is basically the Rai-typical ko-itame but which tends to a certain extent to nagare and might even show masame here and there. In addition, we usually see shirake or a shirake-utsuri on his blades and not the nie-utsuri from Rai main line. Also his hamon is a hint more narrow and subdued and has a lesser emphasis on nie than that of Rai Kunitoshi. So we have here again the junction where you were following the Rai Kunitoshi road but then come across nagare-masame and shirake and have to fork to one of the Rai sidelines like Ryôkai or Enju. And then the hamon and bôshi should tell you, in the ideal case, if you took the right exit. But of course, sometimes it can be very had to tell if a blade is a Rai Kunitoshi, an early Rai Kunimitsu, or a Ryôkai.

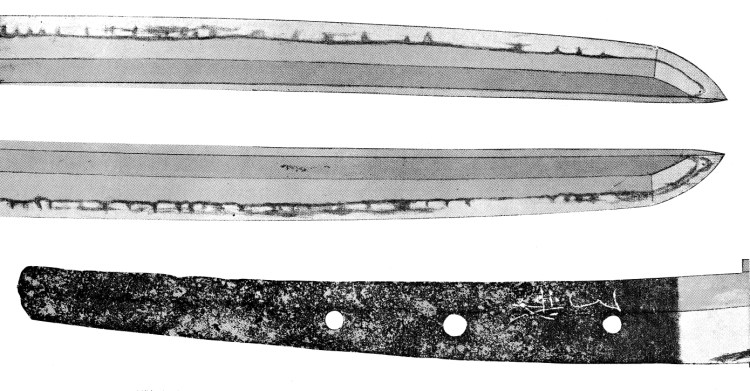

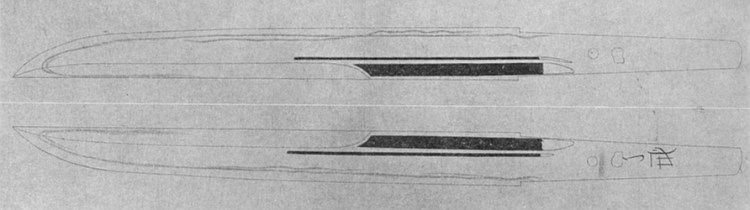

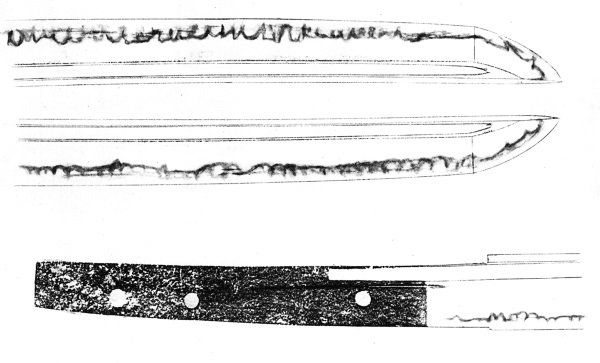

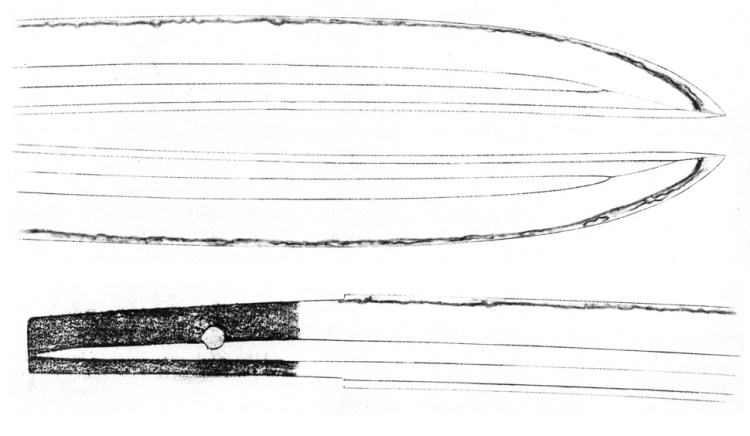

One of his most representative works is the signed tachi that is preserved in the Tôkyô National Museum but which does not hold any status (see picture 1). It is ubu and in this case, the sori tends more to koshizori, also running into a pretty curved kijimomo-style nakago. We see funbari and a ko-kissaki and the kitae is a dense ko-itame that features masame, shirake, and some jifu. The hamon is a suguha in ko-nie-deki that is mixed with ko-midare, ko-chôji, and ko-ashi and the nioiguchi is rather subdued. The bôshi is a midare-komi with a ko-maru-kaeri.

Picture 1: tachi, mei “Ryôkai” (了戒), nagasa 79.98 cm, sori 2.7 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

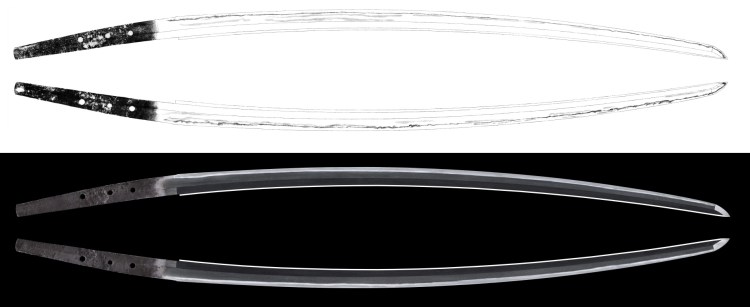

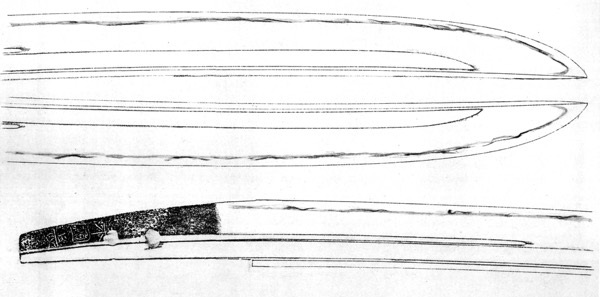

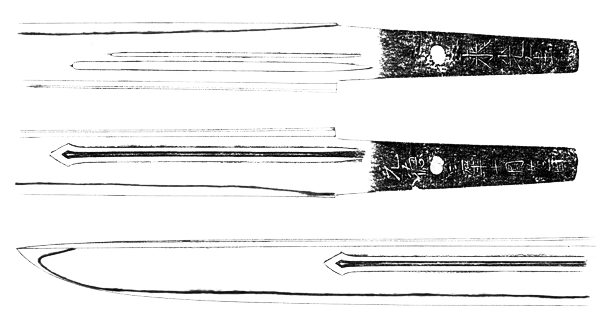

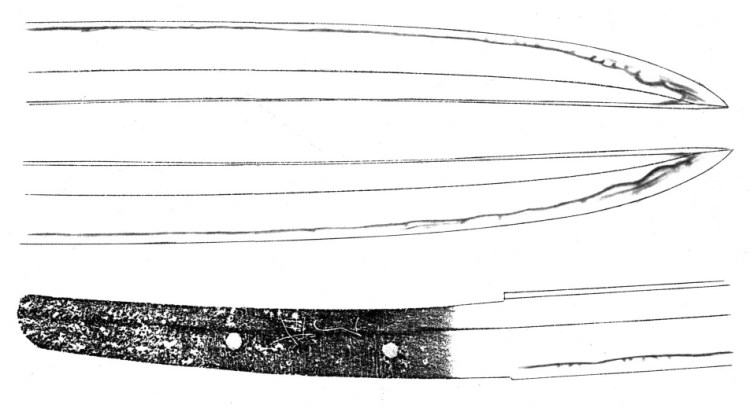

Also very representative is the jûyô tachi that is shown in picture 2. It is ubu too and preserves like the previous blade its long nagasa of 80.3 cm. It tapers, shows funbari and its jigane is an itame that is mixed with masame-nagare and that shows ji-nie and shirake. The hamon is a chû-suguha in ko-nie-deki which tends a little to shallow notare and that is mixed with ko-midare, yô, some kinsuji, and many ko-ashi. The nioiguchi is rather tight and subdued and the bôshi is a slightly undulating sugu with a ko-maru-kaeri whereas the ura side features hakikake. Thus with the rather wide ha with its abundance of hataraki and the quality of the jiba place this work pretty close to Rai Kunitoshi. By the way, this blade was one of those that were submitted to (and passed) the very first jûyô-shinsa in 1958. It was once a heirloom of the Hisamatsu-Matsudaira (久松松平) family, the daimyô of the Iyo-Matsuyama (伊予松山藩) fief.

Picture 2: jûyô, tachi, mei “Ryôkai” (了戒), nagasa 80.3 cm, sori 3.0 cm, motohaba 3.0 cm, sakihaba 1.65 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

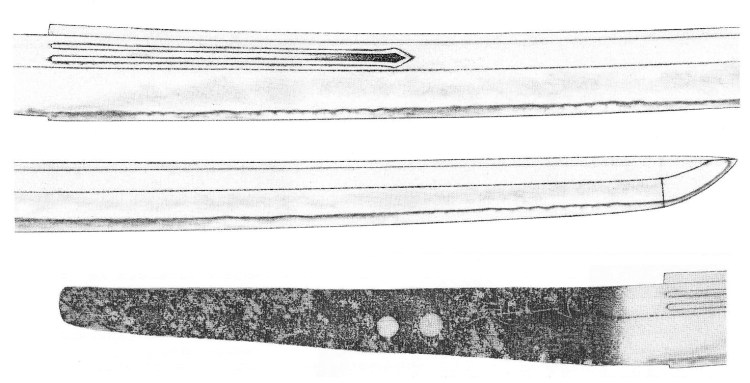

Another signed tachi of Ryôkai that is almost ubu is shown in picture 3. The blade was shortened to 71.0 cm but keeps its rather deep sori (which tends again somewhat to koshizori). We still see a hint of funbari, a noticeable taper, and a ko-kissaki. The jigane is an itame with a conspicuous amount of masame and features ji-nie and a shirake-utsuri. The hamon is a gentle suguha in ko-nie-deki with a little shallow notare and is mixed with ko-gunome and some faint nijûba in places. The bôshi is sugu to notare-komi with a ko-maru-kaeri.

Picture 3: jûyô, tachi, mei “Ryôkai” (了戒), nagasa 71.0 cm, sori 2.3 cm, motohaba 2.7 cm, sakihaba 1.4 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

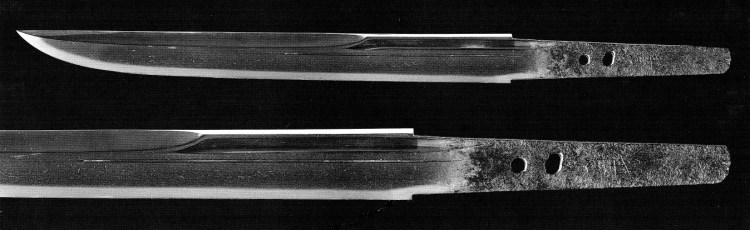

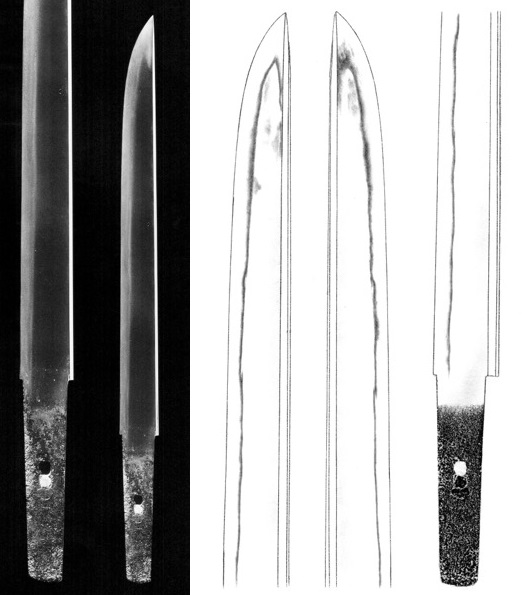

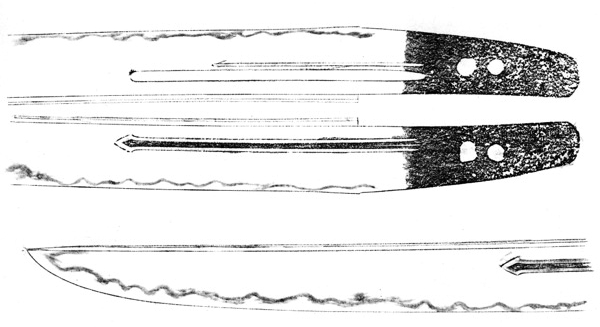

The tachi in picture 4 is one of Ryôkai’s highly classical, calm, and unobtrusive interpretations. It is ubu and signed, slender, has a rather deep koshizori, tapers noticeably, shows funbari, a high shinogi, and a ko-kissaki. The kitae is a densely forged but also somewhat standing-out ko-itame that is mixed with nagare-masame, some ô-hada, and jifu. In addition, ji-nie and a shirake-utsuri appear. The hamon is a suguha in ko-nie-deki that is mixed with a little ko-gunome, ko-midare, ko-ashi, yô, and some fine kinsuji and sunagashi. The nioiguchi and the entire ha are more subdued. The bôshi is a narrow sugu with a brief ko-maru-kaeri. On the omote side we see a suken at the base and there are several tachi of Ryôkai known that bear such a short suken or koshibi at the base.

Picture 4: jûyô, tachi, mei “Ryôkai” (了戒), nagasa 75.65 cm, sori 2.8 cm, motohaba 2.85 cm, sakihaba 1.5 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

*

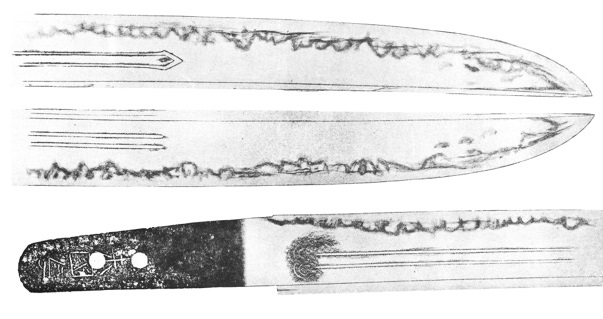

Now we come to his tantô, the most famous of course the meibutsu Akita-Ryôkai (秋田了戒) which is designated as a jûyô-bunkazai (and was even holding the status of kokuhô for a while, i.e. until many designations were reassessed by the Agency for Cultural Affairs after WWII). The name of the meibutsu goes back to the fact that it was once work by Akita Sanesue (秋田実季, 1576-1660) who held the title of Akita Jônosuke (秋田城之介). Later it became an heirloom of the Kaga Maeda family. There are several tantô extant by Ryôkai which are interpreted in kanmuri-otoshi-zukuri. The jigane is an itame that is mixed with masame and that shows ji-nie and some shirake-utsuri. The hamon is a suguha in ko-nie-deki with a tight nioiguchi and nijûba and the bôshi is rather pointed and features a rather wide and long running-back kaeri, also with nijûba.

Picture 5: jûyô-bunkazai, tantô, mei “Ryôkai” (了戒), nagasa 27.2 cm, muzori

An outstanding tantô of him can be seen in picture 6. It is tokubetsu-jûyô and is with the moderate dimensions, the uchizori, and the curved furisode-nakago quite classical. The jigane is a dense ko-itame with fine ji-nie and a shirake-utsuri and the hamon is a chû-suguha in ko-nie-deki with some ko-ashi, yô, and nijûba in places that features a tight nioiguchi. The bôshi is sugu with a rather wide ko-maru-kaeri. On the omote side we see a suken with on top of it a bonji and on the ura side gomabashi, both running with kaki-nagashi into the tang. The tang is ubu by the way, so the second mekugi-ana and the kaki-nagashi of the horimono do not speak for a suriage in this case. There is no nagare-masame or “weakness” in the jigane and so this tantô comes pretty close to Rai Kunitoshi.

Picture 6: tokubetsu-jûyô, tantô, mei “Ryôkai” (了戒), nagasa 24.9 cm, very little uchizori, motohaba 2.35 cm, hira-zukuri, mitsu-mune

As it will be addressed in the next chapter, the Ryôkai lineage also made some naginata and a shortened one, a naginata-naoshi wakizashi, can be seen in picture 7. It is relative wide and bears on both sides a central shinogi-hi, i.e. a groove that runs along the shinogi. The jigane is a dense ko-itame with some nagare and ji-nie and the hamon is a hoso-suguha in ko-nie-deki that is mixed with ko-gunome, kinsuji, and sunagashi. The bôshi runs out as yakitsume and taking into consideration the overall course of the ha, we learn that this was once a shizuka style naginata (more on that interpretation here).

Picture 7: jûyô, naginata-naoshi wakizashi, mumei, attributed to Ryôkai, nagasa 40.6 cm, sori 0.9 cm, motohaba 2.9 cm, iori-mune

Picture 7: jûyô, naginata-naoshi wakizashi, mumei, attributed to Ryôkai, nagasa 40.6 cm, sori 0.9 cm, motohaba 2.9 cm, iori-mune

But Ryôkai also made some more uncommon blade shapes, like for example the one in shôbu-zukuri seen in picture 8. Well, the blade has a nagasa of 68.2 cm and is classified, due to the position of the mei, as tachi but it might well be one of these longer uchigatana that come mostly in hira-zukuri that were made by some of the great Kamakura masters for a higher ranking clientele (like the Nakigitsune-Kuniyoshi, see here). The blade has a relative deep sori and shows a dense itame that is mixed with nagare in places and with ô-hada along the upper half of the omote side. In addition, ji-nie and a shirake-utsuri appear. The hamon is a suguha in ko-nie-dei that is mixed with some ko-ashi and fine sunagashi and kinsuji and that shows some ko-gunome along the monouchi. The bôshi is formed out of these ko-gunome elements and runs back with a short ko-maru-kaeri and some hakikake.

Picture 8: jûyô, tachi, mei “Ryôkai” (了戒), nagasa 68.2 cm, sori 1.8 cm, motohaba 2.7 cm, shôbu-zukuri, iori-mune

Picture 8: jûyô, tachi, mei “Ryôkai” (了戒), nagasa 68.2 cm, sori 1.8 cm, motohaba 2.7 cm, shôbu-zukuri, iori-mune