Looking for certain references regarding Taikei Naotane (大慶直胤, 1779–1857) for an upcoming article, I came across two unrelated blades with kind of interesting inscriptions, which I thought I may share with my readers.

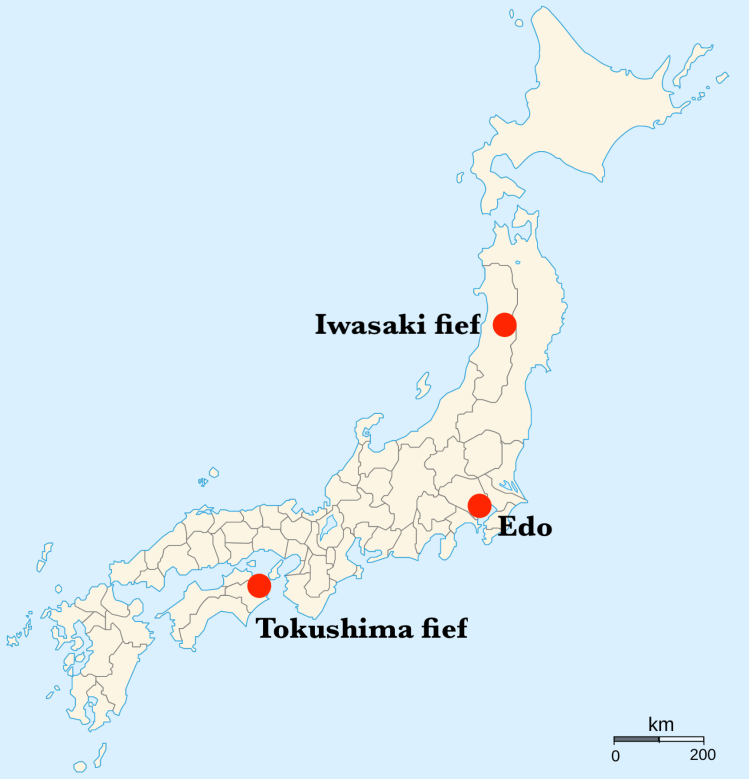

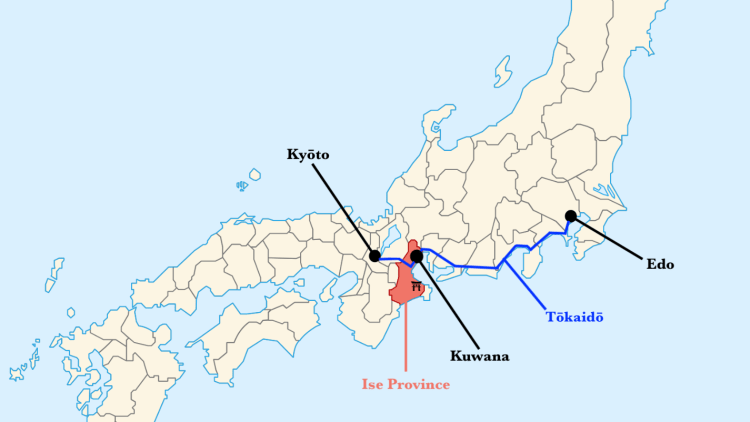

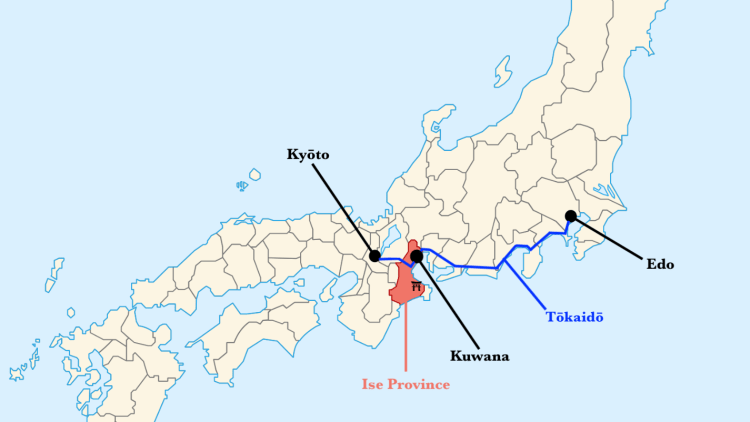

With this article, we find ourselves in Kuwana (桑名) at the end of the Edo period, a town and its surrounding feudal domain of the same name located in Ise province (present-day Mie Prefecture). So, as always, I would like to start with a historical detour before we arrive at the blades in question.

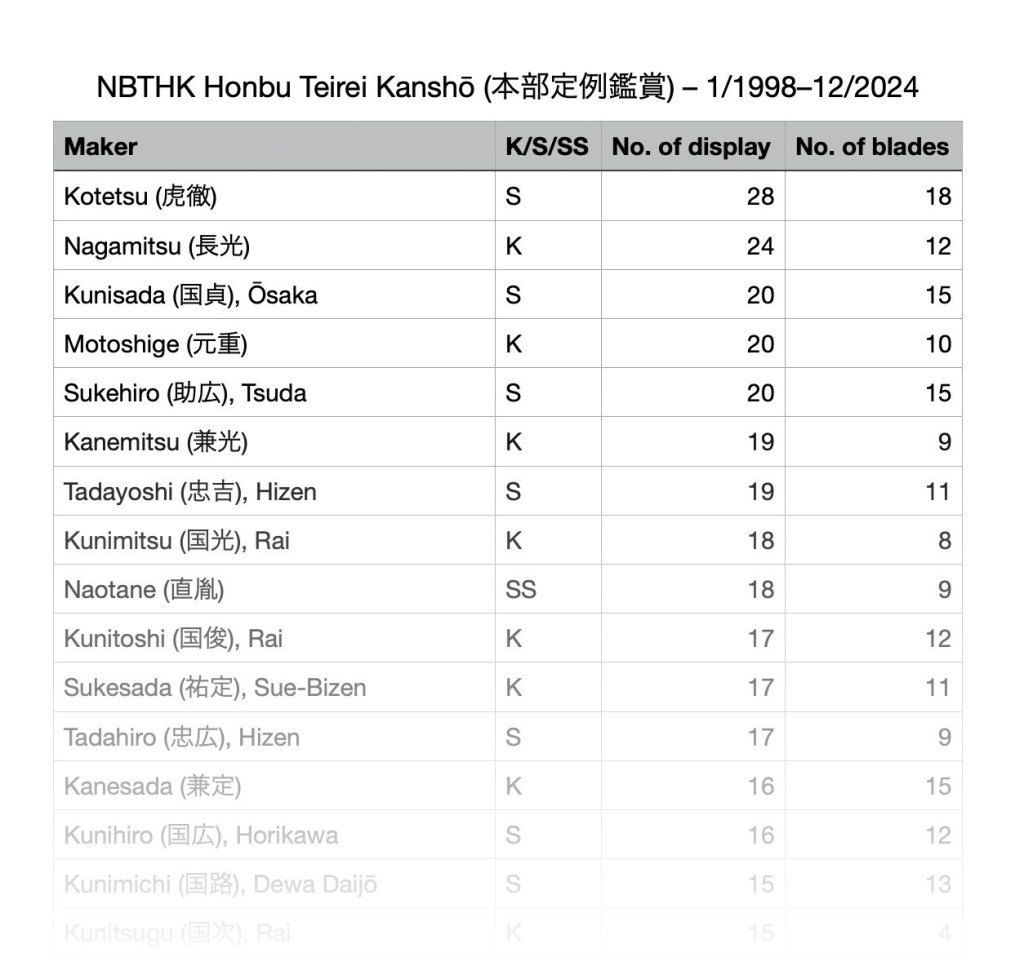

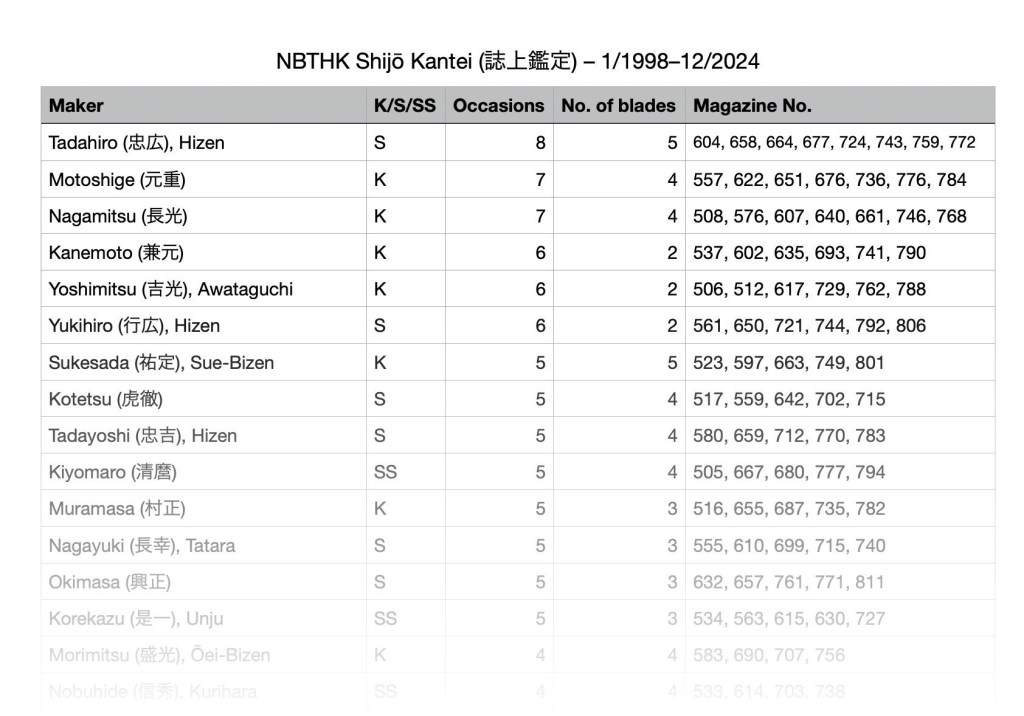

Now, when the names Kuwana and Ise province are dropped, most of you likely think of the famous Muromachi-period smith Muramasa (村正) and his Sengo (千子) School. This is understandable, as the region was not home to that many renowned masters before and after him, i.e., during the Shintō and Shinshintō eras, with basically one exception, but more on him in a second. We know that the Sengo School made it into the Edo period, and continued to produce some few blades locally until the mid-Edo, just about to when the Shinshintō era started. Apart from that, there was also a contemporary local group of smiths, who all shared the name Toshinaga (歳長), but as indicated, not that much was going on sword-wise in Kuwana in the early to mid-Edo period. The reason for why this was the case woud be a topic for another, a more specific article, but things changed in the later Shinshintō era and towards the end of the Edo period.

The indicated most famous and arguably by far best Kuwana smith of this time period was Koyama Munetsugu (固山宗次, born 1803, recorded until 1870). Munetsugu was born in the north, in Mutsu province, in the Shirakawa Domain (白河藩) that was ruled by the Matsudaira (松平) family. When the Bakufu relocated the Matsudaira from Mutsu to Kuwana in Bunsei six (文政, 1823), Munetsugu followed a few years after, but then worked for the Kuwana domain from Edo for the remainder of his career. However, this article is not about Koyama Munetsugu either.

As you can see in the map shown above, Kuwana was a station on the Tōkaidō main road that connected Kyōto and Edo, which means it was well visited by Samurai on their way to, or back from Edo in course of the sankin-kōtai system. In addition to that, Kuwana was also a hub for people making a pilgrimage to the Ise Shrine located in southern Ise province (see little shrine symbol in map), and housed the port to get to the Atsuta Shrine from the western part of the Tōkaidō. In short, and especially because of the presence of said seaport, Kuwana was a busy town with lots of travelers and transit traffic.

And now we slowly arrive at our actual topic. There was a production line going on in Kuwana at the end of the Edo period, which the one or other surely has heard of: Kuwana-uchi (桑名打ち), lit. “made in Kuwana” or “of Kuwana make.” Definitions of Kuwana-uchi vary slightly, but in a nutshell, they are mostly defined as due to the raising popularity of Bizen works in course of the fukkotō revival movement of the Shinshintō period, certain smiths of Kuwana created a quite massive production line of forgeries of them, ranking from Ōei-Bizen (応永備前) to Sue-Bizen (末備前), but usually not containing the old Kamakura or Nanbokuchō masters.

Now, those Kuwana-uchi can range from very cheap and obvious fakes to sophisticated works and signatures that even fool experts. As a rule of thumb, Kuwana-uchi may be best detected through their too tightly forged jigane without much visible forging structure, that is, tending very much to muji, and their hamon with a too tight and “hard” looking nioiguchi featuring yakigashira that are frayed (kuzure) in places. That aside, we do not know for certain who produced those Kuwana-uchi. Some speculate that even Koyama Munetsugu was involved in his early years, whilst others focus on a group of Mishina (三品) School smiths that had relocated there from Kyōto (more on them shortly). Whoever made those forgeries, they certainly had a large team of supporting craftsmen around them as it is said that the production time was astonishingly short. Now, before we finally arrive at the blades in question that I wanted to introduce here, some thoughts on the logistics of Kuwana-uchi.

As mentioned, Kuwana was a large travel hub for Samurai, and it was often the case that a group had to spend several days there because of heavy rain obstructing the ferry and boat service. So, some speculate that some just bought a sword or two during their stay as they were cheap, maybe also one as a gift for someone in their hometown. As I have pointed out in one of my articles on Samurai income during the Edo period, however, most Samurai did not have the financial means to buy new swords whenever they wanted, let alone as gifts for someone. However, it is possible that people were saving money to buy one at one of their upcoming stays in Kuwana in a year or two, or three… As indicated, the sankin-kōtai system made it kind of predictable when that would be. Also, some speculate that sword buying in Kuwana likely took place in a much more planned manner. That is, higher ranking Samurai in charge of the fief’s arsenal or involved with military build-up policies may have ordered swords in large numbers whilst in Kuwana for them to be picked up by their men when they come through town the next time. The same goes for sword dealers all over the country. Incidentally, the anecdote exists that in case travelers were stuck in Kuwana for several days or so because of heavy rain as mentioned, the smiths could ramp up the production so that the blades would be ready whenever the weather cleared up…

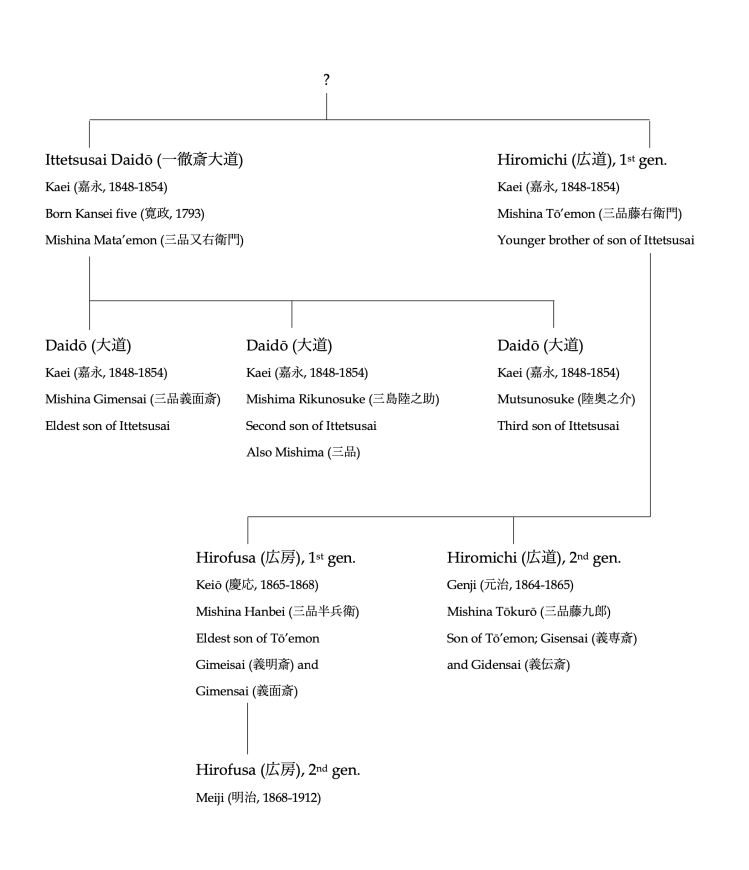

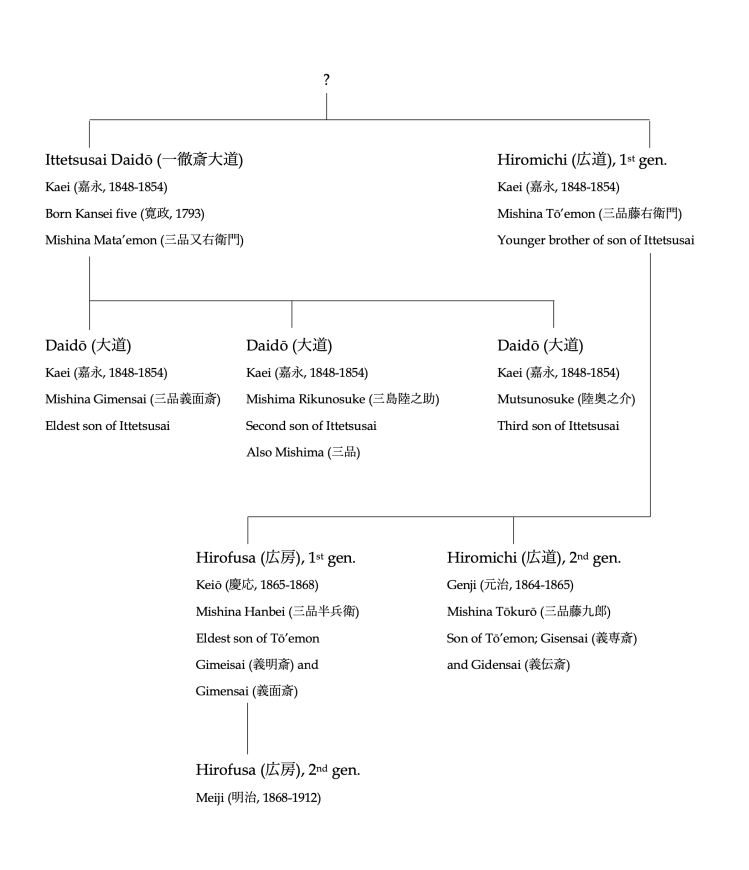

Anyway, back to the aforementioned Mishina group. We experience a certain gap in local sword making between the phasing out of the Shintō groups around Meiwa (明和, 1764–1772) and the arrival of Mishina Mata’emon (三品又右衛門), who signed with the name Daidō (大道) and who used the gō Ittetsusai (一徹斎). I have not been able to find yet exactly when and why Daidō moved from Kyōto to Ise, and it appears that he did not even live in Kuwana, but in Shiroko (白子), which is located about 27 km (17 miles) to the south of Kuwana. This Daidō claimed to be the successor of the famous Momoyama-era Mutsu no Kami Daidō (陸奥守大道) in ninth generation, which may be true or not, but which may also be an allusion to Mutsu no Kami Daidō having claimed that he had been the successor of Shizu Saburō Kaneuji (志津三郎兼氏) in ninth generation as well. Daidō had three sons (or possibly just two as the second and third son, Rikunosuke and Mutsunosuke, respectively, may have been the same person), who all signed with the name Daidō as well. Apart from that, he had a younger brother, Hiromichi (広道), who is also listed as his son. Hiromichi, real name Mishina Tō’emon (三品藤右衛⾨), had two sons, Mishina Hanbei (三品半兵衛) the eldest, who signed with the name Hirofusa (広房), and Mishina Tōkurō (三品藤九郎), who succeeded as second generation Hiromichi. And also Hirofusa had a son, the second generation Hirofusa, whose real name is unknown. For a better understanding, see the genealogy below.

KuwanaGenealogy (PDF)

Now, this entire local Mishina sub-group under Hiromichi was located in Kuwana, and because they were fairly skilled smiths – and because of Hirofusa using the gō Gimeisai (義明斎), which some interpret as a pun and a reference to counterfeit signatures (gimei, 偽銘) – the tradition exists that it was them who were producing said Kuwana-uchi, or were at least in an overseeing function of their production. The latter could also be conceivable from the point of view of the Mishina family having acted as an official liaison between the Imperial court and swordsmiths regarding the granting of honorary titles. In other words, the Mishina were very business savvy in terms of swords, so they could have ventured out to initiate the Kuwana-uchi… (also maybe of interest is the last paragraph of this article I posted in 2016).

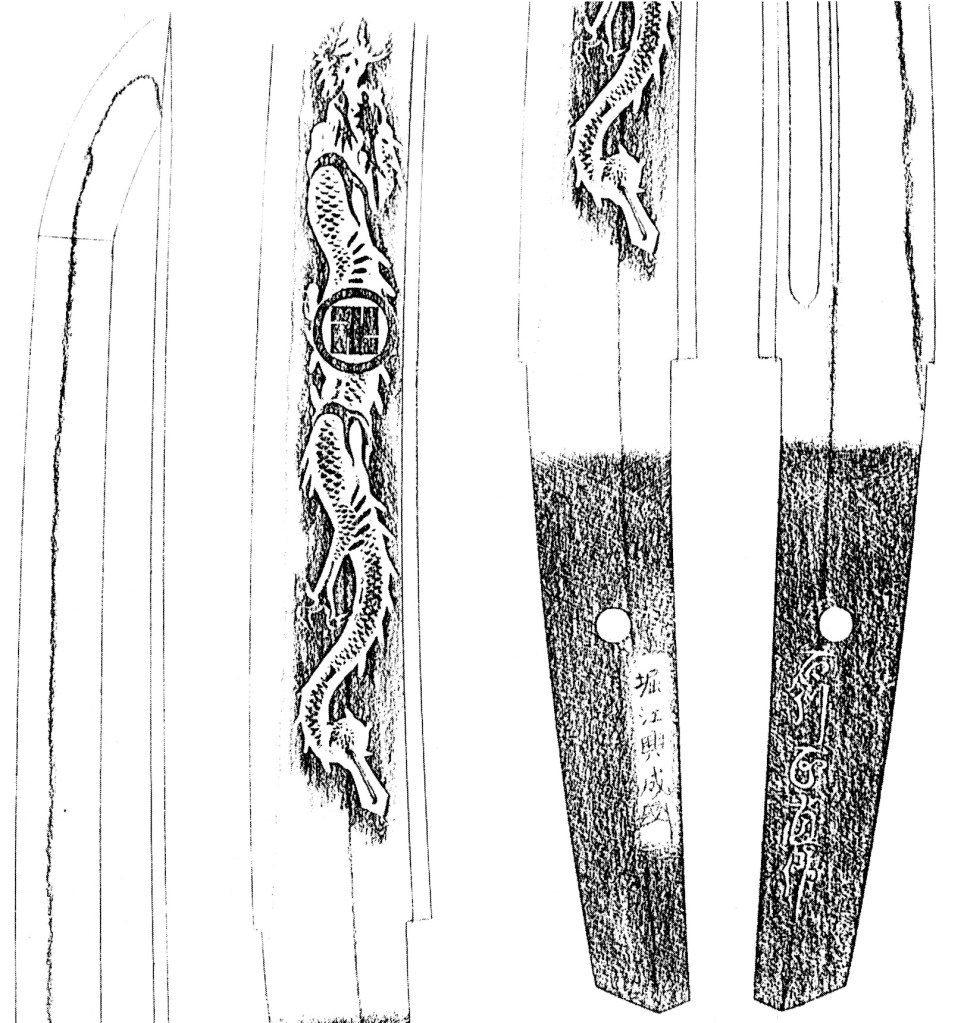

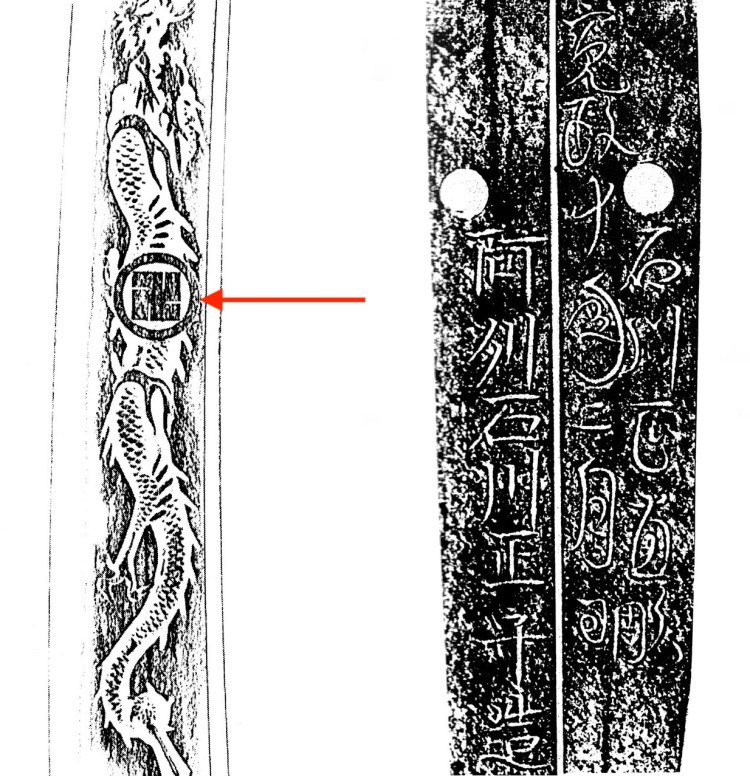

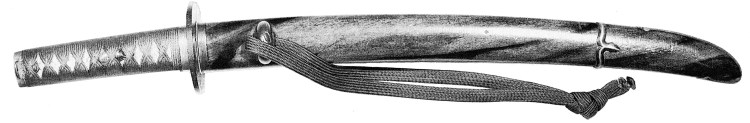

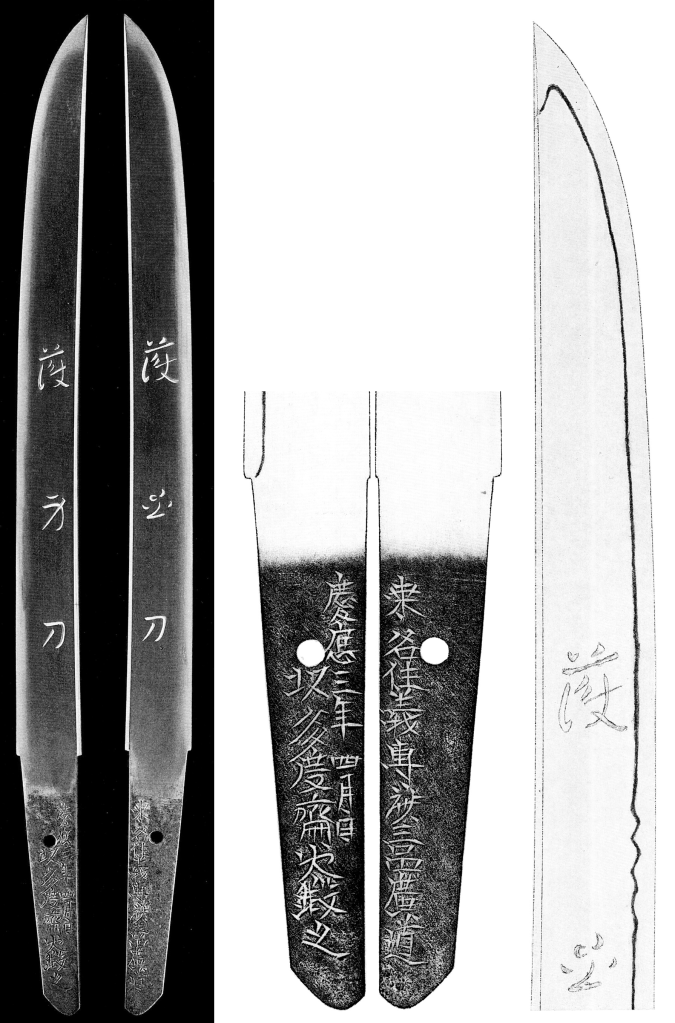

All that said, and after a long read, I would like to introduce two non-Kuwana-uchi blades that were produced by Mishina Hiromichi and Hirofusa under their own name, of course, with a focus on their signatures. The one by Hiromichi, a hira-zukuri ko-wakizashi (Picture 1) is signed:

桑名住義専斎三品広道・慶応三年四月日、以多度斎火鍛之

Kuwana-jū Gisensai Mishina Hiromichi – Keiō sannen shigatsu hi, Tado no imubi o motte kore o kitaeru.

“Forged by Gisensai Mishina Hiromichi, resident of Kuwana, on a day of the fourth month of Keiō three (1867) by using ‘pure fire’ from Tado.”

Picture 1: Nagasa 33.8 cm, sori 0.3 cm, motohaba 3.0 cm.

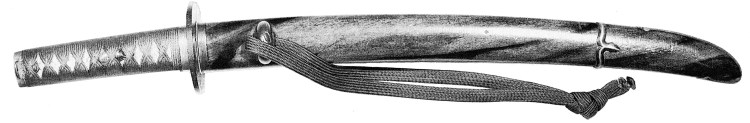

Picture 2: Koshirae of Hiromichi blade.

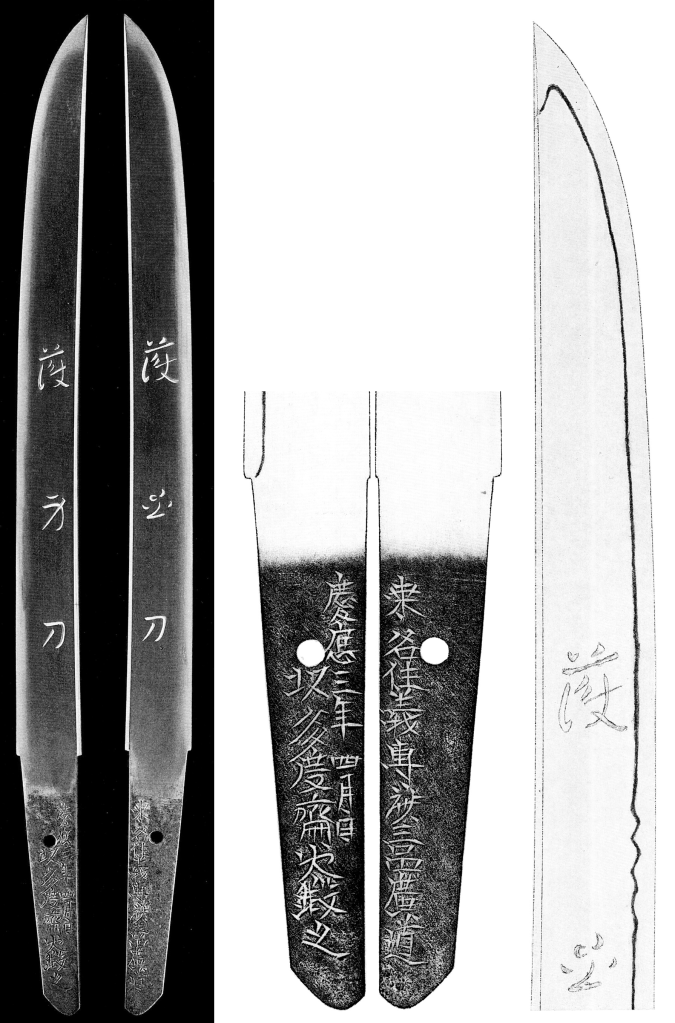

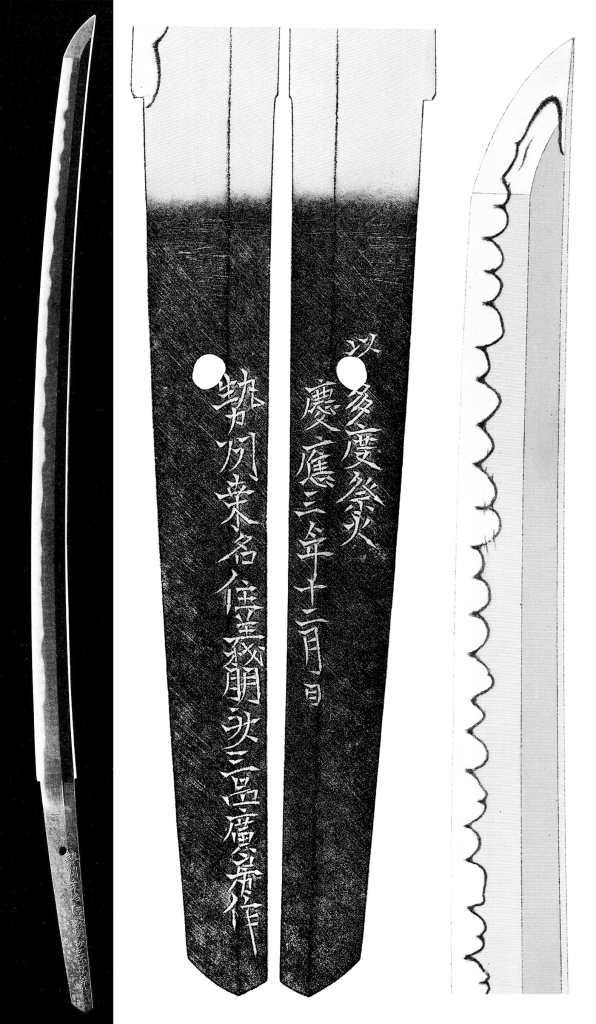

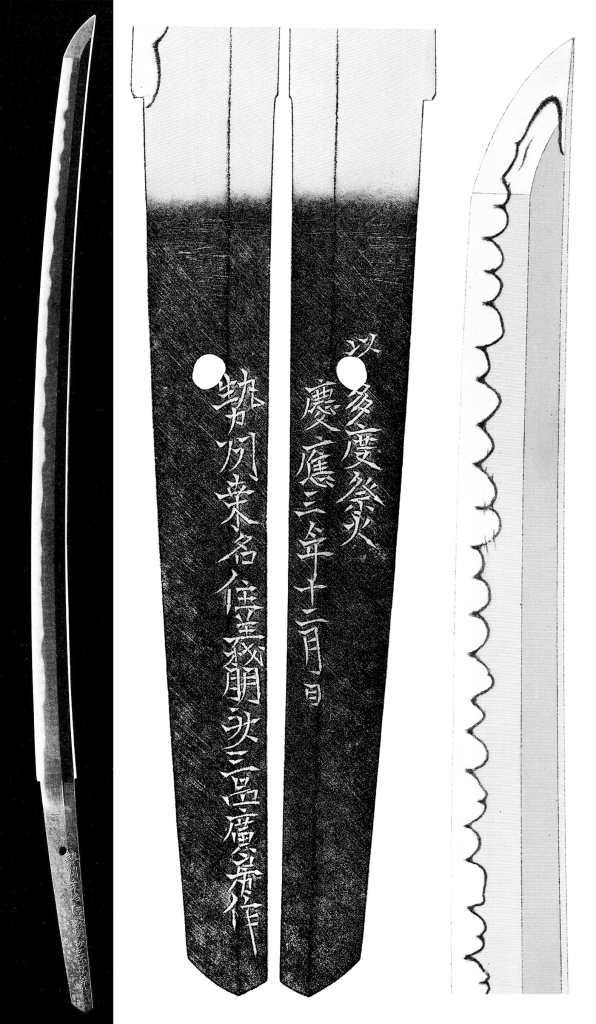

And the one by Hirofusa, a katana (Picture 3), is signed:

勢州桑名住義朋斎三品広房作・慶応三年十二月日、以多度祭火

Seishū Kuwana-jū Gimeisai Mishina Hirofusa saku – Keiō sannen jūnigatsu hi, Tado no matsuribi o motte.

“Made by Gimeisai Mishina Hirofusa, resident of Kuwana in Ise province, on a day of the twelfth month Keiō three (1867) by using ‘ritual fire’ from Tado.”

Picture 3: Nagasa 66.0 cm, sori 1.4 cm, motohaba 3.4 cm.

The supplements in the signatures of these two blades is actually what I wanted to show you. That said, I also wanted to provide some historic background regarding Kuwana and Kuwana-uchi and not just show two blades with brief info. As mentioned in several of my past articles, I have been become more interested in the historic/cultural aspect of Japanese swords over the last ten years than in minutiae of workmanships (itame here, mokume there, etc.).

Picture 4: Associated shrine of the Tado Shrine.

First, Tado in said signatures refers to the Tado Shrine (多度大社) located about 10 km (6 miles) north of downtown Kuwana. The Tado Shrine – allegedly founded in the fifth century CE and then rebuilt by Honda Tadakatsu (本多忠勝, 1548–1610) in 1602 after it had been burned down by Oda Nobunaga (織田信長, 1534–1582) in 1571 – is a Shintō shrine that consists of a main and an associated shrine, and the latter worships Amenoma Hitotsu no Kami (天目一箇神), the patron deity of ironworking and blacksmiths (Picture 4). Second, imubi (斎火), also read imibi, means “Pure Fire” and refers to a, well, “pure fire,” which must be lit in a ritualistic manner by a Shintō priest only using a traditional hand drill (hikiri, 火鑽り) (Picture 5). Said imubi/imibu, referred to as matsuri-bi by Hirofusa, was used for certain Shintō rituals, for example, cooking offerings to the kami.

Picture 5: Shintō priest starting an imubi by using a hikiri.

So, after being lit, the “Pure Fire” was transported from the shrine down to the smith’s district (Kaji-machi, 鍛冶町) of Kuwana and to the Mishina workshop of Hiromichi and Hirofusa (which the entire sub-group likely shared), where it was used to ignite the fire in their forge to begin the sword making process. This all was likely done with the Samurai clients in mind, who wanted that little bit extra to their blades, of course for a certain extra fee… However, we also must not be too dismissive. This was an extremely tense time in Japanese history. The Tokugawa Shōgunate was literally just about to end (both blades are dated 1867), and with the developments that took place over the last one or two decades (Commodore Perry landing at Uraga, for example), uncertainty was the biggest dictate of the moment. Meaning, it is more than understandable that when you order a new blade during these times, you may also want some divine protection, and to conclude, the horimono on the Hiromichi ko-wakizashi also perfectly encapsule this moment: Goshin-tō (護身刀) on the obverse, and Gokoku-tō (護国刀) on the reverse, meaning “blade for self-defense” and “blade for defending the country,” respectively…