Now to the third of the Six Awataguchi Brothers, Kuniyasu (国安), who bore the first name “Tôsaburô” (藤三郎), the honorary title of Yamashiro no Kami (山城守), and who was goban-kaji smith of the fourth month. He is traditionally dated around Shôji (正治, 1199-1201), that means to the very end of the Heian and the beginning of the Kamakura period. Accordingly, we can see at him a shift towards wider and somewhat more magnificent blades. In short, he made elengant and slender but also relative wide and long tachi with a chû instead of a ko-kissaki, the former being close to works of his older brothers Kunitomo and Hisakuni. He also added relative often bôhi. In addition, we know blades with a fine jigane but much more with a rather standing-out itame that tends to nagare and even ô-hada in places. That is why Kuniyasu is known as forging the most standing-out jada of all Six Awataguchi Brothers. That all and the fact that we are facing slightly different signature stiles and relative many extant works has lead to a two generations theory in which the alleged second generation is dated around Kenchô (建長, 1249-1256). But it is well possible that there was just one Kuniyasu, in other words, he might had been active somewhat longer than some of his brothers and just reacted towards the end of his career to then trends in sword fashion. Incidentally, the Kotô Mei Zukushi says that the youngers of the six, Kunitsuna, died in Kenchô seven (建長, 1255) at the age of 93, what calculates his year of birth as Chôkan one (長寛, 1163). Also Kunitsuna, who moved later to Kamakura, made magnificent and powerful blades. So if we assume that the Six Brothers were born not that far apart, Kenchô seems perfectly fine as career end and there is no need for introducing a second generation Kuniyasu.

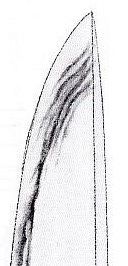

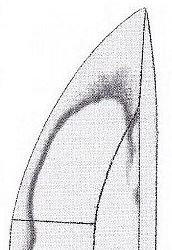

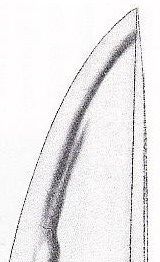

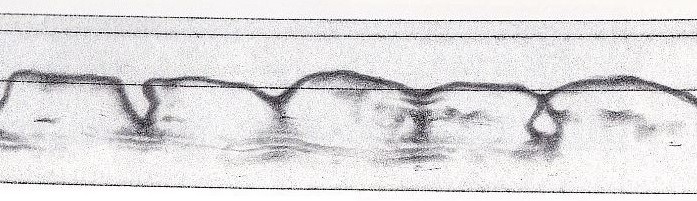

Picture 1: Characteristic features of Awataguchi Kuniyasu’s workmanship.

Apart from the above mentioned features, i.e. hada for Awataguchi-mono rather on the rough side and often bôhi, Kuniyasu hardened mostly a sugha-chô that is mixed with ko-midare, ko-chôji, and ko-gunome of which the individual elements are densely arranged and tend to appear in a connect manner, especially the ko-gunome. Besides of that, we see kinsuji and sunagashi (sometimes prominent) and small uchinoke-like elements atop of the yakigashira which are referred to as karimata (雁股, bifurcated arrowheads). These karimata were later adopted by Rai Kuniyuki (来国行) and became one of his characteristic features but they can also be seen on some swords of Ayanokôji Sadatoshi (綾小路定利). In addition, Kuniyasu’s nioiguchi is not as clar as at Hisakuni. That in turn means, you can mix up his works with that of Ayanokôji Sadatoshi as Sadatoshi too is known for applying groups of several ko-gunome and/or ko-chôji elements embedded into a rather subdued nioiguchi and accompanied by yubashiri and nijûba that create that peculiar “layered” appearance of the ha. Major difference between their works is the bôshi as Sadatoshi’s bôshi is noticeably more nie-laden and shows hakikake and nie-kuzure. Kuniyasu’s bôshi is more calm and appears as only slightly undulating sugu with a ko-maru-kaeri. However, some blades of Kuniyasu also show hakikake and a more wide kaeri, so some of his works are pretty close to Sadatoshi. But apart from that we can say that Kuniyasu’s entire ha is a little more calm than that of Ayanokôji Sadatoshi, that means we see a hint more ups and downs at blades of the latter. The more standing-out hada of Kuniyasu might also remind of Ko-Hôki Yasutsuna (安綱) but Yasutsuna’s blade are overall more rustic, i.e. they have a darker steel, a jifu-utsuri with antai (what gives the ha a rather “brindled” appearance), and ha-bie and hotsure that are interwoven into a conspicious ha-hada. As for Kuniyasu’s tangs, they mostly tend to kijimono, show katte-sagari yasurime, and a kurijiri. There are only niji-mei of Kuniyasu known which are signed with a kind of semi-cursive character for “yasu” with large curves for the vertical strokes, although we can see some differences (but which probably go all back to different phases in the career of a single smith). Please note that Ko-Bizen Kuniyasu signed in a similar manner (see picture 2). So watch out but Ko-Bizen Kuniyasu’s blades should be different in terms of hamon (more flamboyant) and sugata (he was active in the mid-Kamakura period).

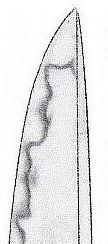

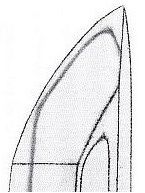

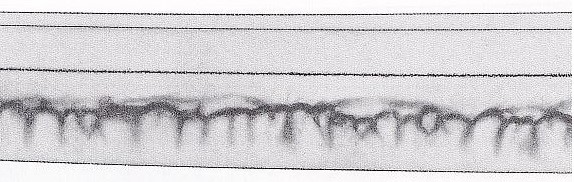

Picture 2: mei comparison, to the left Awataguchi Kuniyasu, the one to the right Ko-Bizen Kuniyasu

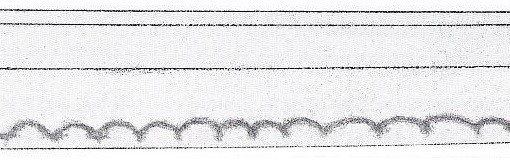

The blade shown in picture 3 was a former heirloom of the Mizuguchi family (溝口), the daimyô of the Shibata fief (新発田藩) of Echigo province, and is today designated as jûyô-bunkazai. It is a little on the wider side but is overall very elegant, shows funbari, and ends in a ko-kissaki. The kitae is a dense itame with plenty of ji-nie and the hamon is a ko-nie-laden ko-midare to suguha-chô along the upper area that is mixed with some prominent ko-chôji and that comes with a rather subdued nioiguchi. We also see some kinsuji and sunagashi and the bôshi is sugu with a ko-maru-kaeri.

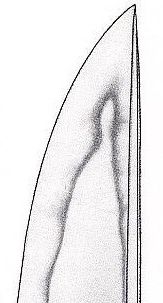

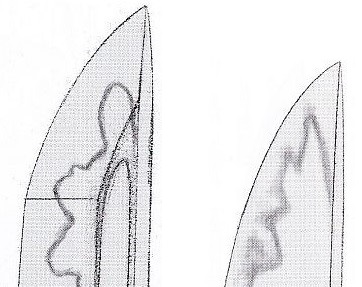

Picture 3: tachi, jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Kuniyasu” (国安), nagasa 79.3 cm, sori 2.9 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

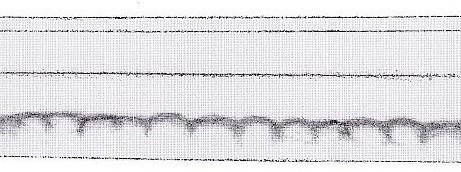

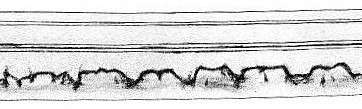

Next I want to introduce a tachi of Kuniyasu that is preserved in the Tôkyô National Museum but that has no whatsoever designation. It is again a little wide, has a deep koshizori with funbari, and a compact chû-kissaki and the kitae ist a rather standing-out ko-itame with ji-nie. The hamon is a ko-nie-laden ko-notare that is mixed with ko-midare, many ko-ashi and yô, kinsuji, and sunagashi and the bôshi is midare-komi with a ko-maru-kaeri. Please see here to get some impression of the steel of this blade and its overall perfect condition.

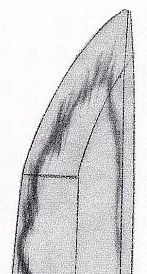

Picture 4: tachi, mei “Kuniyasu” (国安), nagasa 79.4 cm, sori 2.7 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

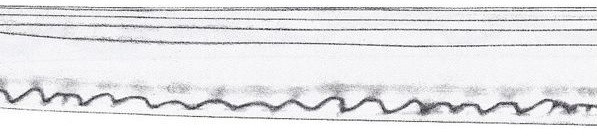

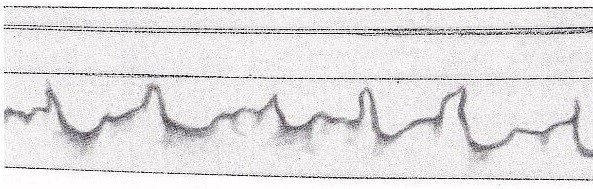

And as last work of Kuniyasu I want to introduce the jûyô-bijutsuhin tachi that was once owned by the Matsudaira branch (松平) which was in control of the Tsuyama fief (津山藩) of Mimasaka province and which is now preserved by the NBTHK. It is shows a standing-out itame mixed with mokume and nagare and also fine ji-nie, chikei, and a faint nie-utsuri appear. The hamon is a ko-nie-laden suguha-chô mixed with plenty of ko-ashi and yô, kinsuji, sunagashi, and discontinuous yubashiri and nijūba along the yakigashira that create the very “layered” apperance. The ha does not show conspicious ups and downs and its midare elements are densely arranged. The bôshi is sugu with a ko-maru-kaeri and please note that this blade bears futasuji-hi.

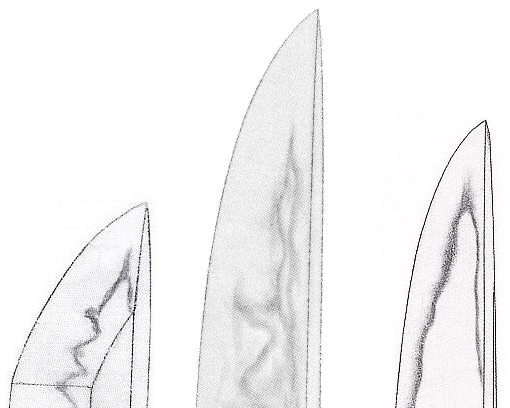

Picture 5: tachi, jûyô-bijutsuhin, mei “Kuniyasu” (国安), nagasa 71.4 cm, sori 2.7 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

*

Kuniie’s fourth son was Kunikiyo (国清). He bore the first name Tôshirô (藤四郎) and the Kotô Meizukushi Taizen says that he also signed with “Shirôbei” (四郎兵衛) and that he was around Genryaku (元暦, 1184-1185) 30 years old. As for Kunikiyo, we only have two authentic signed and a few ô-suriage mumei works attributed to him to work with. The jûyô-bunkazai tachi (picture 6) was once owned by the Satake (佐竹) family, the daimyô of Akita, and handed down within them as Awataguchi work since the early Edo period. The other signed work is a jûyô-bijutsuhin but which bears quite a differently chiselled mei. It was once owned by the pre-WWII collector Saitô Moichirô (斎藤茂一郎), who owned several bunkazai, bijutsuhin, and kokuhô, but Honma said that its provenance is unclear. However, he also says that despite of the differences in their mei, both blades are more classical than Rai works and he has no problem with seeing them as Awataguchi-mono. Honma was not sure if the blades go back to the same smith but for him, the differences in mei are too great to see them as just going back to different phases of a single smith’s career. And in this course he was also not sure which one was the fourth of the Six Awataguchi Brothers. Tanobe too remarks the somewhat “hesitatingly” chiselled mei of the jûyô-bijutsuhin but rather tends to think that we are facing signatures of two different active periods of a single smith. Incidentally, there was another Awataguchi Kunikiyo but he was a student of Kunitsuna and active too late (around Kôan [弘安, 1278-1288]) for attributing any of these blades to him.

Anyway, the jûyô-bunkazai is elegant, has a rather shallow sori, funbari, and a ko-kissaki. The kitae is a dense ko-itame with fine and bright ji-nie and shows a faint but beautiful nie-utsuri. The hamon is a ko-chôji in ko-nie-deki that is mixed with ko-midare, ko-gunome, karimata-like elemements, small tobiyaki and yubashiri atop of the yakigashira in places, ashi, yô, sunagshi and kinsuji. The ha is quite complex and its elements are densely arranged and we can see a strong resemblane to works of Kuniyasu. Kunikiyo’s ha is just a little wider, the sori more shallow, and the shinogi-ji somewhat broader. Please note that Tanobe describes this blade at one place as having a deep koshizori but what is probably a mistake.

Picture 6: tachi, jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Kunikiyo” (国清), nagasa 79.4 cm, sori 2.2 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

Picture 7 shows a tachi of Kunikiyo that is tokubetsu-jûyô and attributed via “Den” to Awataguchi Kunikiyo. It has a deep koshizori that bends down towards the tip and shows a rather standing-out itame mixed with some nagare, plenty of ji-nie, and much chikei. The hamon is a nie-laden suguha-chô mixed with some notare, ko-midare, gunome, ashi, some yubashiri along the monouchi, kinsuji, and many fine sunagashi. The nioiguchi is bright and clear and the bôshi is sugu with a short maru-kaeri and nijûba. The tang is ô-suriage, shows a shallow kurijiri, and shallow katte-sagari yasurime. This blade was once a heirloom of the Sakai (酒井) family, the daimyô of the Himeji fief (姫路藩) of Harima province.

Picture 7: tachi, tokubetsu-jûyô, mumei “Den Awataguchi Kunikiyo” (伝粟田口国清), nagasa 69.8 cm, sori 2.6 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

*

Arikuni (有国) was the fifth son of Kuniie and his first name was Tôgorô (藤五郎). Unfortunately, there is only one signed blade known by him, a tachi (picture 8) that had been shortened to an uchigatana (per nagasa definition a wakizashi today) but whose signature was preserved via orikaeshi. It was once owned by a certain Nakasawa (中沢) from Nagoya but who offered it to the Ise Shrine. The blade remains despite of the suriage an elegant shape that still gives you an idea of the noble and refined original tachi-sugata. It shows a compact ko-kissaki with a hint of ikubi and a dense ko-itame that is mixed with some nagare and masame and that appears with its abundance ji-nie as nashiji-hada. The hamon is a hoso-suguha in ko-nie-deki and the bôshi has a ko-maru-kaeri. Please note that there was another Awataguchi Arikuni smith active from whom a blade dated Kagen two (嘉元, 1304) is extant. Some see him as a possible later generation of Kuniie’s son but the Kokon Meizukushi Taizen lists him in its genealogic section as son of Kunitsuna, although beneath of Kunitsuna’s alleged other son, Kunihiro (国弘), what means that he possibly could have been Kunitsuna’s grandson.

Picture 8: wakizashi, jûyô-bunkazai, orikaeshi-mei “Arikuni” (有国), nagasa 56.3 cm, sori 0.9 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

Next time I will introduce Kunitsuna (国綱), the sixth and youngest son of Kuniie, before we continue with the Awataguchi main line after Kunitomo and sons and students of the Six Brothers.