Awataguchi Hisakuni (久国) was the second son of Kuniie and thus the second oldest of the so-called “Six Awataguchi Brothers.” He is listed with the first name Tôjirô (藤次郎) what makes sense as “Jirô” means “second son.” So the “Fuji” from Fujiwara was combined with the fact that he was the second son and this approach was kept for all other sons of Kuniie who were named Tôsaburô, Tôshirô, Tôgorô, and Tôroku (the youngest went without the suffix rô). Just his first son Kunitomo is an exception as he was called Saemon, or if we follow the “Fuji” character integration approach, Tôzaemon, or Tôrinzaemon if we also integrate the alleged family name Hayashi. Anyway. Hisakuni had the honor to become the sword forging instructor of Emperor Gotoba and received for this the honorary title of Ôsumi Gonnokami (大隅権守) and an extra intracalary month was added to the monthly-based goban-kaji to include him in the list. In addition, Gotoba also conferred titles of the ancient courtly Smiths Office (kanuchi no tsukasa, 鍛冶司) upon smiths who worked for the goban-kaji project. For example, Hisakuni was made head of all Yamashiro smiths (Yamashiro Kokuchû Kaji Chôja, 山城国中鍛冶長者) and entrusted with Bizen-Ichimonji Nobufusa (延房) – who was the other sword forging instructor of Gotoba – with another courtly sword office, namely that of the Nihon Kaji Sôchô (日本鍛冶惣庁). Those titles and the fact that Gotoba had chosen him as teacher (it is said that he worked for eight years with the retired emperor) speaks for the great skill of Hisakuni and virtually all experts agree that Hisakuni was the best of all Awataguchi smiths. Incidentally, the Kotô Meizukushi Taizen states that he died in Kenpô four (建保, 1216) at the age of 67, that means he was three years younger than Kunitomo (if we believe in this data).

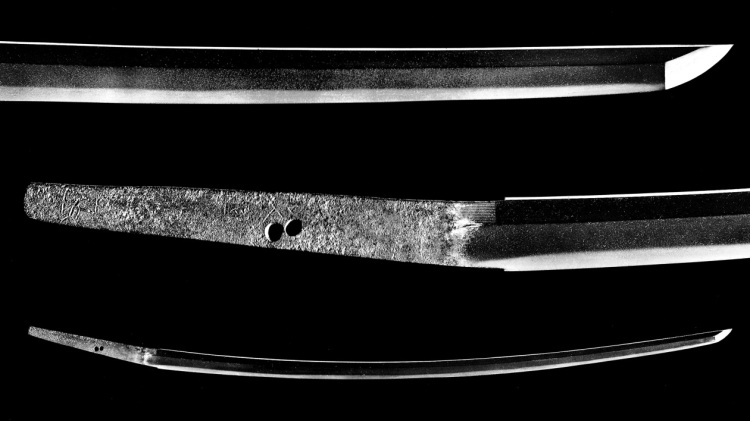

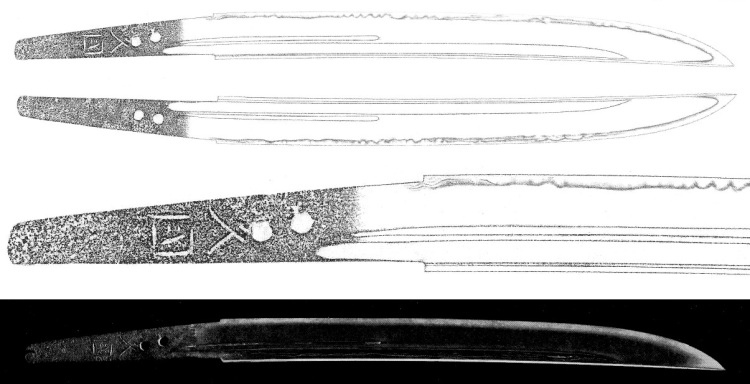

Fortunately, there are relative many works of Hisakuni extant, both tachi and tantô. Like Kunitomo, and due to the local and chronological context, he made highly elegant and slender tachi with a deep koshizori that bends down towards the tip, funbari, and a ko-kissaki that might tend to a little chû. His jigane is of unrivalled quality and also the hamon is perfectly hardened. The fineness and density of his steel is referred to as tataki-tsume (たたきつめ) in old sword publications what means about “as dense as a stamped-down clay floor.” The most famous and best work of him is the kokuhô (picture 1) that was once a heirloom of the Matsudaira (松平) branch which ruled the Saijô fief (西条藩) of Iyo province. It shows a very dense ko-itame whose abundance of ji-nie tends towards nie-utsuri and which appears altogether as nashiji-hada. The hamon is a suguha-chô in ko-nie-deki that is mixed with ko-midare, ko-chôji, ko-gunome, plenty of ko-ashi, some uchinoke, kinsuji and sunagashi in places, and brightly glittering ha-nie. The nioiguchi is very clear and the bôshi is a shallow notare-komi with a short kaeri (almost entirely yakitsume on the ura) with hakikake. The tang is ubu, although its end was altered as the seen on the first and third Kunitomo picture, shows a kurijiri, sujikai-yasurime, and two mekugi-ana. The niji-mei is chiselled right next to the mekugi-ana and it has to be pointed out that this is the thinnest signature known by Hisakuni. Also interesting is that the tang bears at the very end a kaô (picture 2) but which does not go back to the smith. It was added later, probably on behalf of a later owner of the sword.

Picture 1: tachi, kokuhô, mei “Hisakuni + kaô” (久国), nagasa 80.4 cm, sori 3.0 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

Picture 2: Detail of the kaô

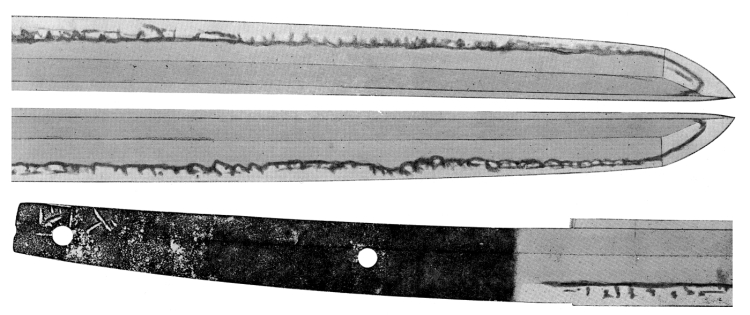

Next I want to introduce the Hisakuni tachi from the Imperial Collection (picture 3). It is suriage and shows a dense ko-itame with plenty of ji-nie and chikei and a suguha that tends to ko-notare and that is mixed with ko-midare, plenty of ashi and yô, and some kinsuji. The bôshi is sugu with a hint of midare and shows a ko-maru-kaeri with nijûba on the omote side. Please note that the signature is noticeably thicker chiselled than that of the kokuhô, what is the more common signature style of Hisakuni (actually, only the kokuhô was signed with that a thin chisel but Tanobe assumes that all known mei go back to the hand of a single smith).

Picture 3: tachi, gyobutsu, mei “Hisakuni” (久国), nagasa 66.7 cm, sori 1.5 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

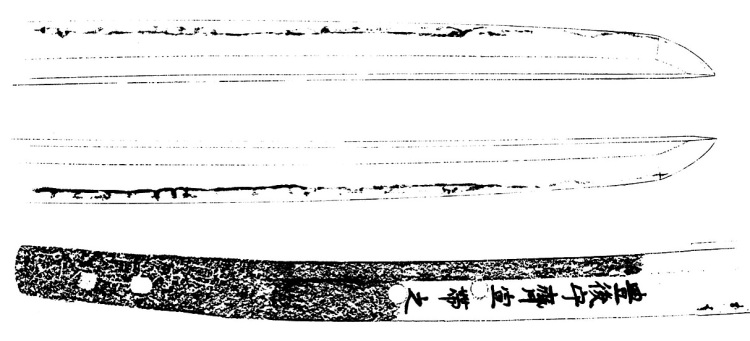

When it comes to long swords of Hisakuni, also the jûyô-bunkazai from the former collection of the Akimoto family (秋元) has to be mentioned (picture 4) as it is regarded as his “second best” work. The tang was shortened like the gyobutsu just as much as to preserve the mei, which was added with the same thick chisel. The kitae is a very densely forged ko-itame with plenty of ji-nie and also an irregular jifu-utsuri with some antai appears. The hamon is a nie-laden suguha that tends to ko-notare and that is mixed with ko-chôji, ko-midare, kinsuji, sunagashi, ha-nie, and seven some ara-nie in places. And with the hakikake in the bôshi and the jifu-utsuri we might say that Hisakuni gave this blade on top of its elegance a hint of power. Please note that like at the gyobutsu, the undulating area of the hamon focuses on the monouchi.

Picture 4: tachi, jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Hisakuni” (久国), nagasa 78.5 cm, sori 1.6 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

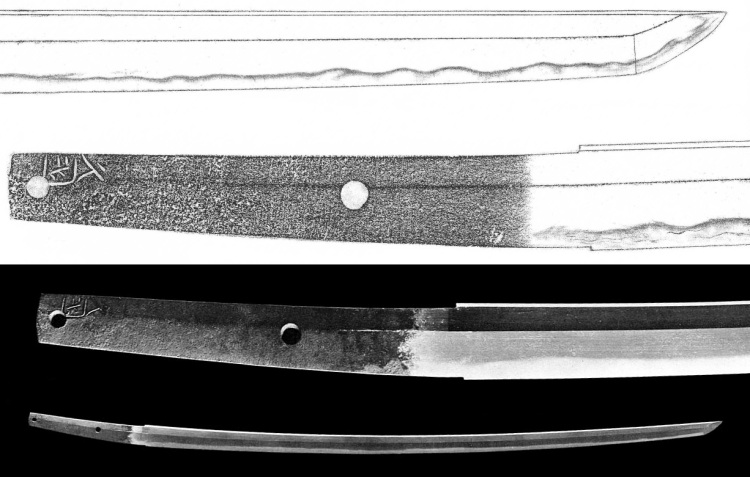

Picture 5: tachi, tokubetsu-jûyô, mei “Hisakuni” (久国), nagasa 74.4 cm, sori 2.0 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, dense itame with a hint masame and plenty of fine ji-nie, the hamon is a suguha-chô in ko-nie-deki with a little shallow notare and is mixed with ko-gunome, ko-midare, ko-ashi, yô, and fine sunagashi, the bôshi is a rather wide sugu-chô with a ko-maru-kaeri, the tang is completely ubu, has a kurijiri, katte-sagari yasurime, and comes in a kijimono-gata, again, we have here the common thickly chiselled mei of Hisakuni

*

Now to Hisakuni’s tantô. The majority of them is small dimensioned and has an uchizori that shows a hint of takenoko (i.e. can appear as more pronounced uchizori). By the way, Hisakuni is often quoted when it comes to the earliest extant fine tantô. And then there is the wide, long, slightly curved, and almost Nanbokuchô-esque jûyô-bijutsuhin tantô of Hisakuni that is the odd one out. But the signature and deki of the jiba is a total match with the other works of Hisakuni and experts agree that this is just one of the more rare dagger interpretations that were occasionally ordered at that time. Well, the blade shows a ko-nie-laden suguha-chô that is mixed with connected ko-gunome, yubashiri that create nijûba and kuichigaiba in places, and some kinsuji and sunagashi. The bôshi is sugu with a rather long running-back ko-maru-kaeri. On both sides a bôhi with a shorter soebi at the base is engraved.

Picture 6: tantô, jûyô-bijutsuhin, mei “Hisakuni” (久国), nagasa 29.4 cm, hira-zukuri, mitsu-mune

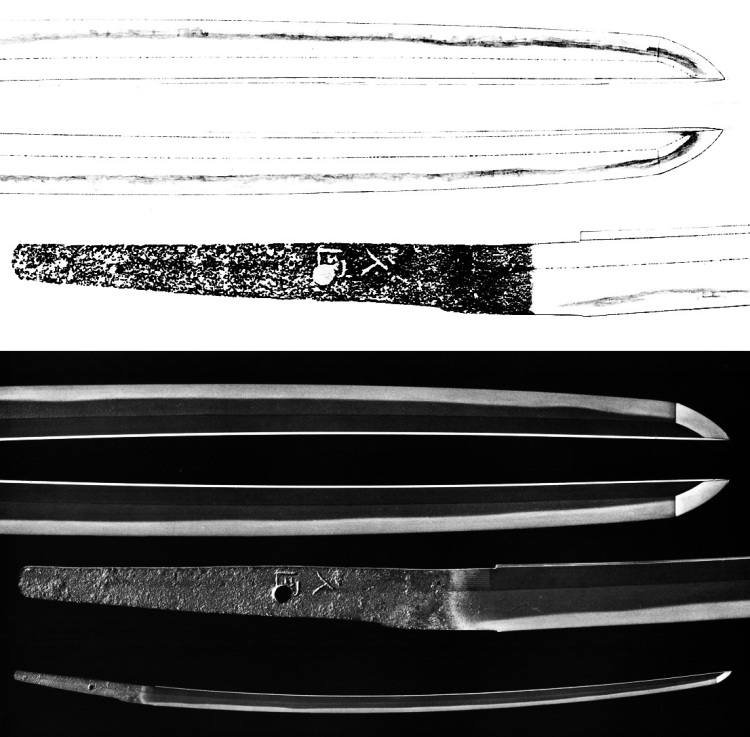

The most representative tantô of Hisakuni (and regarded by some as one of the finest of all Awataguchi tantô) is the jûyô-bunkazai that was owned liked the kokuhô by the Saijô-Matsudaira family (picture 7). It is slender, as mentioned small dimensioned, has a rather pronounced uchizori, and shows a very dense ko-itame with fine ji-nie that tends to form nie-utsuri. The hamon is a ko-nie-laden suguha-chô that is mixed with ko-midare, kinsuji, and sunagashi, and we have the same tendency towards nijûba and kuichigaiba as seen on the sunnobi-style jûyô-bijutsuhin. The bôshi is sugu with a little midare-komi and has a ko-maru-kaeri.

Picture 7: tantô, jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Hisakuni” (久国), nagasa 20.1 cm, uchizori, hira-zukuri, iori-mune

Picture 8, an heirloom of the Date (伊達) family, shows one of the more rare blades of Hisakuni that is signed with his first name. It is a slender jûyô-tantô that shows a very fine and densey forged ko-itame with ji-nie which appears as nashiji-hada. The hamon is a hoso-suguha in ko-nie-deki with a prominent yakikomi at the machi and with hotsure. The ha widens along the fukura and runs back with a ko-maru-kaeri. The omote side shows three bonji and the ura side a suken.

Picture 8: tantô, jûyô, mei “Tôjirô Hisakuni” (藤次郎久国), nagasa 22.4 cm, uchizori, hira-zukuri, iori-mune

There is also one tachi signed that way (picture 9), a jûyô that bears a kinzôgan-mei with the name of its former owner – Shimazu Narinobu (島津斉宣, 1774-1841), the ninth daimyô of the Satsuma fief – on its tang. It is slender, preserves despite of the suriage a deep sori, and shows an itame with some nagare and ji-nie. The hamon is a nie-laden suguha-chô mixed with chôji, ko-midare, sunagashi, kinsuji, and plenty of ha-nie. The bôshi is a thin sugu with a ko-maru-kaeri.

Picture 9: tachi, jûyô, mei “Tôjirô Hisakuni” (藤次郎久国) kinzôgan-mei “Bungo no Kami Narinobu kore o haku” (豊後守斉宣帯之), nagasa 68.4 cm, sori 2.2 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune