It is said that the Awataguchi School goes back to a certain Kuniyori (国頼) but who was not a swordsmith, at least it is noted so in the old genealogies which add the supplement “hi-kaji” (非鍛冶, also read “kaji arazu”), lit. “no smith.” So his successor Kuniie (国家) – who is listed as “started to educate himself to become a swordsmith” or “the first [of the school] who carried out the profession of a swordsmith” – is regarded as de facto founder of the school what in turn renders Kuniyori the school’s “ancestor” if you want. Kuniie is also listed as being a “descendant of Yamato´s Kôfukuji (興福寺),” whatever that means, because no source goes into detail about what relationship Kuniie had to this temple. The Kotô Mei Zukushi Taizen states that Kuniyori was an armorer from Yamato and that his son Kuniie lived in Tanba (丹波), in the Soekami district (添上郡) of Yamato province which was an area that became a part of present-day Tenri (天理), Nara Prefecture. The Kôfukuji is about 10 km to the north of Tanba/Tenri. So not sure if these two traditions, i.e. being affiliated with the Kôfukuji and living/working in Tanba go hand in hand. I want to do some research on the jôji-hôshi (承仕法師) in the future, the so-called “monk craftsmen” or “monk workers” of a certain temple. Maybe I am able to come across something which helps us in this matter. The Kotô Mei Zukushi Taizen dates Kuniie around Tenshô (天承, 1131-1132) but the meikan date Kuniyori around Bunji (文治, 1185-1190) and Kuniie around Genryaku (元暦, 1184-1185), that means both towards the very end of the Heian period. As mentioned repeatedly in this blog, these dates have to be taken with a grain of salt, so even if Bunji was later than Genryaku, there is a certain grey area and the dates do not rule out at all that Kuniyori and Kuniie were father and son. Well, if it is true that Kuniie became a swordsmith with his move to Kyôto, we have no records that tell us who his master was. In addition, there are no blades of Kuniie extant which would allow us to draw some conclusions on the basis of workmanship. I would like to refer to the Japanese practice of tôri-ji (通字) or kei-ji (系字) at this point, the practice of a lineage or school of sharing a common character. When we assume that Kuniie was in Kyôto around Genryaku (元暦, 1184-1185), under whom could he have studied? Neither the Ayanokôji nor the Rai School had been established at that time. The Sanjô School seems a bit too early so maybe Gojô comes into question. Their latest known master, Kuninaga (国永), is traditionally dated around Tengi (天喜, 1053-1058) but as mentioned in the relevant chapter of this series, it is very likely that there were several generations Kuninaga active. So with the practice of tôri-ji in mind, we can speculate that Awataguchi Kuniie might had been a student of a later Kuninaga. But it is of course also possible that the very character for “Kuni” had already been shared in his lineage of armorers and Kuniie so to speak brought it with him from Nara and his use of “Kuni” has nothing to do with the lineage of Gojô Kuninaga. Anyway, I said at the beginning of this series that I don’t want to go too much into historic detail and focus on kantei. But I also said I will introduce some historic background if it is necessary for the understanding of a certain subject. And the establishment of the Awataguchi School is such a case because as mentioned in the following, Kuniie’s six sons and their successors turned out to be the greatest masters of their time. It is thus hard to accept that a school like the Awataguchi came out of nowhere. So either Kuniie was a later and skilled smith from the lineage of Gojô Kuninaga, or he was a skilled armorer who reacted to the then local demand for elegant swords for the aristocracy, studied under a local smith, and worked with his six sons very hard to establish a forge that should become the first point of contact when it comes to high-quality blades. Before I come to the first tangible Awataguchi masters, please take a look here to read about the origins of the Rai School, a post of mine from last year that deals with a famous blade of Kuniyori. So if this blade is authentic and a work of this Awataguchi Kuniyori, then either the armorer approach should be dismissed, or already Kuniyori had changed his profession after his move to Kyôto and not just his son Kuniie. Lastly, I don’t want to leave out what is written in the early Kamakura-period work Uji Shûi Monogatari (宇治拾遺物語). This collection of Japanese tales of unknown author bases on a no longer existing work with the title Uji Dainagon Monogatari (宇治大納言物語), written by Minamoto no Takakuni (源隆国, 1004-1077) who was the Dainagon counselor of Uji. The later Uji Shûi Monogatari writes in Volume 1, Chapter 15: “He entered Kyôto from the Awataguchi Entrance […] nearby where the Awataguchi smiths reside/live.” So it seems that smiths were working there at the latest by the end of the 11th century but what makes this entry even more interesting is that this chapters starts with the words: “This is another old story.” This is a strong indicator for the assumption that the Awataguchi School does not go back to an armorer who had moved there at the very end of the Heian period. It is of course theoretically possible that the Awataguchi School had been active there as Gojô offshoot and mere below the radar level since mid-Heian times and that it was revived by an outsider, i.e. by Kuniie, who brought as a skilled armorer from Nara (the then heartland of master armorers) new blood into the school.

*

Kunitomo (国友) is the earliest Awataguchi smith of whom we have extant blades to work with (leaving aside the aforementioned Kuniyori tantô). He is traditionally dated around Kenkyû (建久, 1190-1199) and was the oldest son of Kuniie. The Kotô Mei Zukushi Taizen states that he died in Kenpô one (建保, 1213) at the age of 67. Again, this information has to be taken with a grain of salt because as stated in my Masamune book, the publication gives for each and very smith his year of birth and death, a data that was not known to earlier authors and just pops up in the Kotô Mei Zukushi Taizen that was published for the first time in Kansei four (寛政, 1792). Just wanted to address that at this point because when I am referring to dates forwarded by the Kotô Mei Zukushi Taizen in the future, I am not going to remind of their doubtfulness. So Kunitomo was summoned by the retired Emperor Gotoba (後鳥羽天皇, 1180-1239, r. 1184-1198) for his so-called goban-kaji (御番鍛冶) project and appears on the initial goban-kaji list as smith for the sixth month, and again on the list that features 24 smiths, on that one for the first month. By the way, also his son Norikuni (則国), his younger brother Kuniyasu (国安), and his nephew Kagekuni (景国) appear on goban-kaji lists and his younger brother Hisakuni (久国), Kagekuni’s father, had the honor to act as personal sword forging instructor of Gotoba. It is also said that Kunitomo’s father Kuniie was given the honorary post of supervisor of all goban-kaji. And this is why I think it is rather unlikely that an outsider came to Kyôto where he founded from scratch a school of sword makers whose smiths were considered right from the start as best of the best.

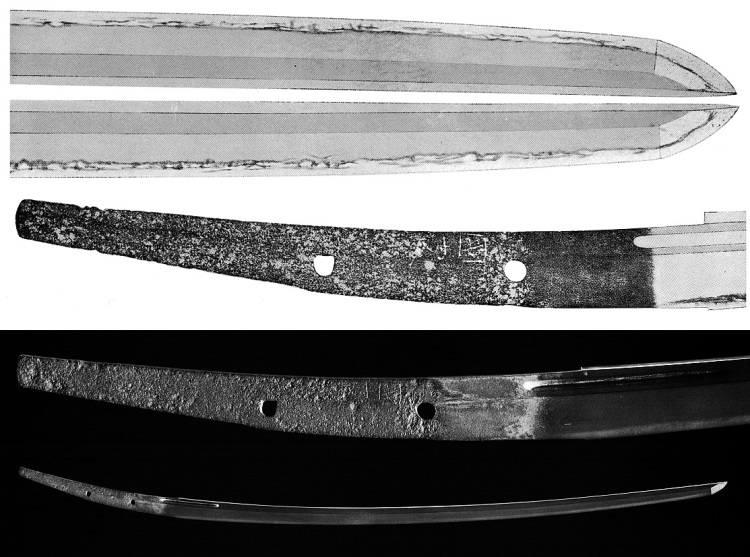

Extant works of Kunitomo are extremely rare and can be counted on one hand. The most famous one is the jûyô-bunkazai tachi that is preserved in the Atsuta-jingû (picture 1). It has a highly elegant and slender tachi-sugata with a deep koshizori that bends down towards the tip, much funbari, and a ko-kissaki. The kitae is a very dense ko-itame with ji-nie and the hamon a ko-nie-laden suguha with ko-ashi. The bôshi is sugu and has a smallish ko-maru-kaeri but appears almost as yakitsume. The tang of this blade is completely ubu. It tapers noticeably, has sujikai-yasurime, a kurijiri, and the finely chiselled mei is placed above the mekugi-ana and towards the back of the tang.

Picture 1: tachi, jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Kunitomo” (国友), nagasa 75.7 cm, sori 2.2 cm, shinogi-zukuri, mitsu-mune

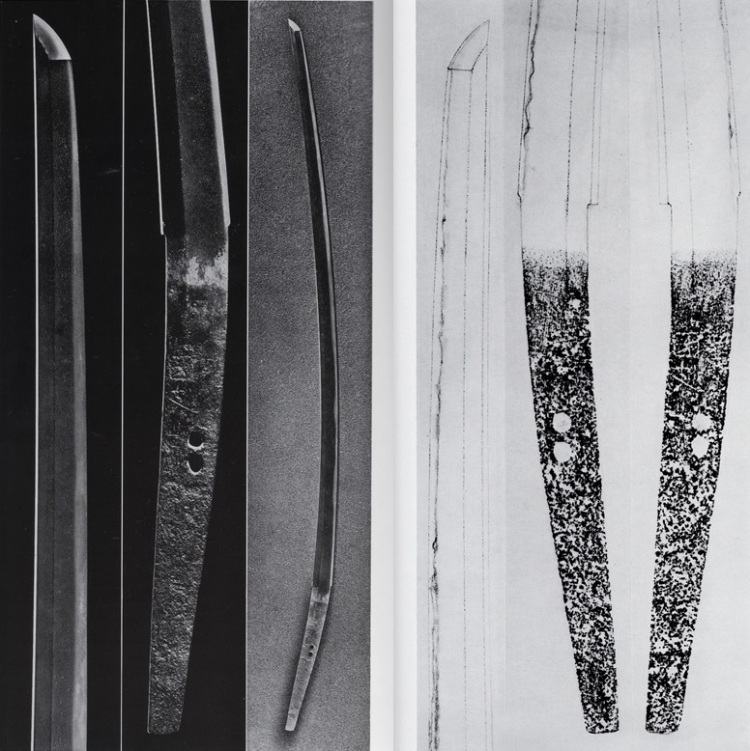

There is only one more signed tachi of Kunitomo known, or at least one more that is definitely attributable to Awataguchi Kunitomo. There is namely a tachi signed “Kunitomo tsukuru” (国友造) owned by the Kurokawa Institute of Ancient Cultures (picture 3) that differs in terms of deki and signature style and that Honma hesitates attributing it to the Awataguchi smith and says it might actually be a Ko-Bizen work but from about the same time of production. However, it goes as Awataguchi work its designation as jûyô-bijutsuhin. Anyway, the other definite signed tachi of Kunitomo is a tokubetsu-jûyô (picture 2) and very close to the tachi of the Atsuta-jingû. It shows the same elegant and slender tachi-sugata with funbari and a deep koshizori but has an iori instead of a mitsu-mune. Also it is a little machi-okuri, although its tang has the original kijimomo-style shape whereas at the Atsuta-jingû blade, the end of the tang seems to have been altered so that it does not have this conspicuous curve. The tokubetsu-jûyô has a very dense ko-itame that is mixed with some itame and nagare in places and that appears with the ji-nie and chikei altogether as nashiji-hada. The hamon is a ko-nie-laden suguha-chô that is mixed with ko-midare, ko-ashi, jô, kinsuji, and sunagashi. The nioiguchi is rather wide and like the Atsuta-jingû blade, the ha tends to urumi in places. The bôshi is sugu and has a smallish ko-maru-kaeri but appears almost as yakitsume. Also we see a hint of hakikake at the very tip. There is a small koshibi on the haki-omote side that runs due to the machi-okuri a little into the tang.

Picture 2: tachi, tokubetsu-jûyô, mei “Kunitomo” (国友), nagasa 74.3, sori 2.2 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

Picture 3: tachi, jûyô-bijutsuhin, mei “Kunitomo tsukuru” (国友造), nagasa 72.4 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, slender and elegant tachi-sugata with a deep koshizori, funbari, and a ko-kissaki, the kitae is an itame mixed with mokume and ji-nie and the hamon is a ko-nie-laden suguha-chô mixed with ko-midare and kinsuji. Well, who am I to question Honma but from the overall interpretation and sugata and especially from the finish of the tang and the position of the signature, it would pass very well as Awataguchi Kunitomo for me.

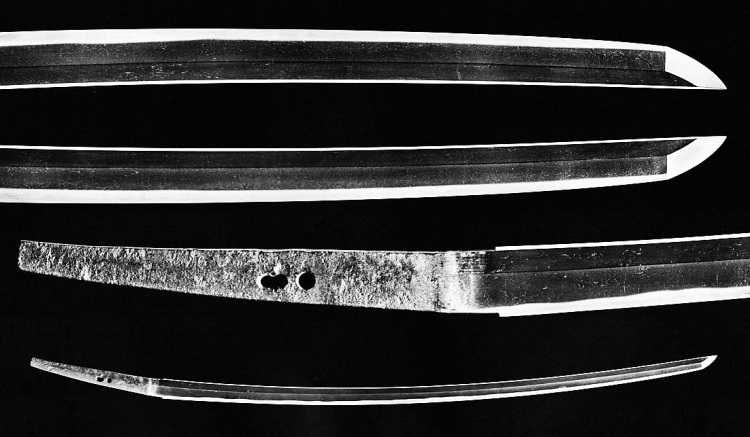

Picture 4: tachi, tokubetsu-jûyô, mumei, attributed to Awataguchi Kunitomo, nagasa 76.6 cm, sori 1.6 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, elegant and slender tachi-sugata with a deep koshizori, funbari, and a ko-kissaki, the kitame is a dense ko-itame mixed with some itame here and there, nagare, ji-nie, and chikei, the hamon is a ko-nie-laden ko-midare mixed with ko-gunome, ko-chôji, ashi, and plenty of kinsuji, the bôshi is sugu with a ko-maru-kaeri with hakikake and kinsuji

*

Honma also says that there are two tantô that bear the mei “Kunitomo” which are no Awataguchi works but whose signatures don’t give the impression of being gimei of Awataguchi Kunitomo either. In other words, they are most likely works of another Kunitomo who is not found in the meikan and whom Honma attributes on the basis of the workmanship to the Yamato tradition, probably Senju’in school (and somewhat later than Awataguchi Kunitomo). Also he says that there are blades going round that bear the niji-mei “Fujibayashi/Tôrin” (藤林). Kunitomo is listed with the name Fujibayashi Saemon (藤林左衛門), although the exact reading or interpretation of this name is unclear. Some read it as “Fuji Hayashi Saemon,” i.e. Hayashi as the family name, “Saemon” as the first name, and “Fuji” referring to the clan name Fujiwara (藤原). Another theory suggests that the entire name is completely read as one first name, i.e. as “Tôrinzaemon.” And the reading “Fujibayashi/Tôrin Saemon” follows the assumption that Kunitomo´s first name was Saemon and that he signed his family name Hayashi and Fuji for the clan name Fujiwara in a conbined version as “Fujibayashi” which can also be read “Tôrin.” Now Honma says that such a Fujibayashi/Tôrin signed tachi was once submitted for an old kichô-tôken shinsa. The blade indeed did look like an Awataguchi-mono but it did not pass because of the suspicious or rather very uncommon signature. And then there is the kanmuri-otoshi-zukuri, kikuchi-yari-style ken signed “Fujibayashi/Tôrin” that was once owned by Naruse Masanari (成瀬正成, 1567-1625), the first daimyô of the Inuyama fief of Owari province. Here too, no one dares to attribute the work to Awataguchi Kunitomo, even if old sword publications say that Kunitomo also signed with the niji-mei “Fujibayashi/Tôrin” and even depict drawings of tangs with this mei.

Hi Markus,

Picture 3 – nagasa is wrong, can’t be 7.4cm, I guess it is 74cm, but not sure

Thanks Jean, is corrected.