And again back to tsuba. The insecure Muromachi period played much into the hands of austere trends, a development that was picked up by Zen and the tea culture. As mentioned, Zen Buddhism was quasi tailor-made for the spirit of the warrior class. Well, practicing Zen was a rather solitary thing but with the tea, which of course also had its strong solitary connotations, the educated warriors had a good way to express and share their taste. The end of the Muromachi period thus “perfected” aesthetic ideals that had already been there, for example the so often quoted ideal of wabi (侘) and sabi (寂). Entire libraries can been filled with books and attempted explanations of this phenomenon and I am not going to ruminate them. What we have to know is that concepts like wabi and sabi had existed before but with somewhat more negative connotations. With the Muromachi period, they were kind of slightly “redefined” and no longer referred just to loneliness of living remote from society, just to name one definition, as now also natural objects and human creations could show, or better “possess” wabi and sabi. The aesthetic of wabi and sabi, and please forgive me in not splitting up these terms here as this would go too far, is an aesthetic of rustic simplicity, of something that was created by chance or nature (or looks as if created by chance or nature), of something that suggests wear. In psychological terms, appreciating wabi and sabi means to accept the transience of life, the fact that not everything can be controlled by human, the passing of time. So wabi and sabi are quite “Zen-ish” aesthetical concepts which, once understood and internalized, gives one much joy in appreciating transient moments and, if you want, simple life.

Of course it took a while until tsuba were reflecting this development and wabi-sabi and tea influences on sword guards might not be seen before the mid-Muromachi period. I have already pointed out that the changes in warfare, society, and rule left their marks on swords and sword fittings. Now it was time to leave behind the sheer practical forms with their naive designs and bring the element “fashion” into tsuba. The simple sukashi that had represented in tentative and unobtrusive manner just patterns from every-day life or maybe religion made place for artistically arranged designs. This development went hand in hand with another one, namely gradually from mere craftsmen like shirogane-shi (白金師・銀師) or tachi-kanagu-shi (太刀金具師) to such that understood themselves as artists, although the first fruits of this change were not to be ripe until the end of the Muromachi period. Representative are the great masters Nobuie (信家) and especially Kaneie (金家) who was the first to introduce real picturesque motifs for tsuba. Pictures 6, 7, and 8 show this development in a highly simplified form.

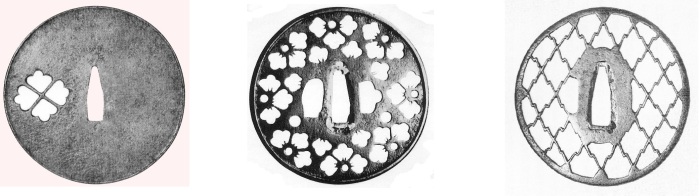

Picture 6: From ko (小) to ki (生) to ji (地) sukashi.

Picture 7: From Ônin to (two) Heianjô to Kaneie.

Picture 8: From tachi-kanagu-shi to Ko-Mino to Ko-Kinkô to Umetada

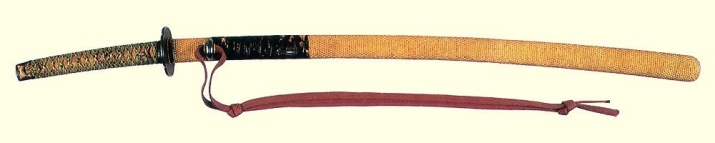

Before entering the Momoyama period, uchigatana were basically mounted in an unobtrusive manner, that means black-laquer saya with the hilt covered in black lacquered same and wrapped in leather and with an iron ji-sukashi-tsuba. This elegant style was the forerunner of the subsequent Tenshô-koshirae (天正拵) (see picture 9), a special mounting that has its name from the Tenshô era (天正, 1573-1592) and which has to be seen as a countertrend to the loud koshirae of the Momoyama period. The Tenshô-koshirae in turn paved the way for the highly tea-oriented Higo-koshirae (肥後拵). Again, the Higo-koshirae was a for a while local trend of its own which followed the basic rules of then high-class uchigatana sword mountings of high ranking warriors but interpreting them according to tea aesthetics (see picture 10). And when I am talking of “basic rules” of that time, I mean that the often quoted flamboyant Momoyama-koshirae are actually not that far away from Tenshô or Higo-koshirae. Just the color scheme is considerably louder (see picture 11).

Picture 9: Tenshô-koshirae

Picture 10: Higo-koshirae

Picture 11: Momoyama-koshirae

So the tsuba of late Muromachi and Momoyama times followed basically either aesthetics of just design (ji-sukashi-tsuba), of more or less simple and refined picturesque interpretations (Ko-Shôami, Shôami, or Kaneie), or of wabi-sabi, whereas of course also in-between, cross-referencing, and hard-to-classify guards existed. I want once more refer to Nobuie-tsuba. These tsuba are made in a highly sophisticated and totally controlled manner but to appear to have natural shapes and a subtle, intentionally rustic, sometimes even archaic, but always very natural surface, terms that perfectly match with the aforementioned brief description of wabi-sabi. The same applies of course to Higo-tsuba which form an artistic world of their own. Another category or rather school of tsuba that emerged in the Momoyama period and which was quite a novelty is Umetada-tsuba. Umetada Myôju (埋忠明寿) was namely the first to transfer the bold but elegant and sometimes even a little bit impressionistic painting style to tsuba that had emerged in the Momoyama period around the artists Hon´ami Kôetsu (本阿弥光悦, 1558-1667) and Tawara Sôtatsu (俵屋宗達).

Picture 12: Nobuie-tsuba, two Higo-tsuba, Umetada-tsuba

Well, things started to change when Tokugawa Ieyasu came to power. As mentioned earlier, the Momoyama Culture is usually declared over when he elemininated the last remaining member of the Toyotomi family at the Siege of Ôsaka in 1615. The stabilization of the bakufu and the taking shape of Edo can be dated around Keian (慶安, 1648-1652) to Kanbun (寛文, 1661-1673) but Edo had a problem: No influential persons from art and culture had settled in the new capital yet. They refused to leave Kyôto, for example Hon´ami Kôetsu, Umetada Myôju, and the Gotô family, what eventually ended in forced displacements and “offers” which came close to blackmail. Apart from that, the Tokugawa-bakufu issued a series of laws and decrees which pretty well defined every aspect of a bushi´s life. It was precisely regulated which sword style had to be worn with which dress and which koshirae a samurai had to wear when attending Edo Castle for example. As we know, the Shogunate introduced in the former half of the 17th century the sankin-kôtai (参勤交代) system through wich each daimyô had to maintain a residence and household in Edo. With this and countless newly created administrative posts and functions in the new capital, the majority of the warrior class had arranged itself quite fast with Edo. And since they had a “head start” of several decades to do their own thing there, new fashions and aesthetic concepts developed locally. Apart from carpenters, roofers, blacksmiths and all forces needed to create the new center of Japan, Edo was until the mid 17th century only something for the venturesome craftsman and artist and for those who fastly reacted to the new trends there and adapted themselves. That means waiting too long could mean missing the train. A group of artists which did everything right was those of the early Akasaka (赤坂) masters. They put up their tents in Edo quite fast and, supposedly coming from Kyôto, produced as fast according to the new style in demand. This style had still its roots in tea aesthetics but gave them a new connotation, reflecting the then situation of the warrior class: Being proudly the now no longer challenged rulers of the country but at the same time “stuck” in a rigid administrative and hierarchical system. The tea ceremony was of course uninterruptedly practiced but it got a more mannerly touch. And this “being caught” feeling combined with a more and more practical, bureaucratic interpretation of the warrior ideals, and the upcoming of a no longer intellectually inferior merchant and later also bourgeois class resulted in the expression of a new aesthetic ideal that is known as iki (いき・粋). Well, iki is no less complex than wabi-sabi but basically it can be circumscribed as sophistication but always mixed with sontaneity, a pinch of romanticism, elegance and smartness by trying not to be complicated and coquettish. Thus iki is sometimes compared to Western dandyism of the early 19th century. For example, if a samurai or chônin didn´t master iki, he came across as artificial and arrogant as their Western counterparts that earned the dandyism a poor reputation.

Picture 13: From Muromachi to Momoyama era ji-sukashi to Ko-Akasaka to later Akasaka-tsuba.

Everything was peaceful and fine with the Edo period and the first real difficulties faced by the bakufu arose during the Kyôhô period (享保, 1716-1736). At the end of the 17th century, the coin reserves of the bakufu were running short, because the major gold and silver mines were exhausted. Added to that, there was a short period of abundance during the Genroku period (元禄, 1688-1704) caused by unusually high prices for rice, and steady prices for consumer goods. This was the administrative outcome of the preceding periods, and it left the daimyô with a new taste for the finer things of life which they didn´t want to give up. At the same time, some merchants started to play in the same financial league of a daimyô or were even wealthier. This brought some noticeable changes for tsuba. The formal arts, like paintings by the Kanô school (狩野) or the classical interpretations of sword fittings by the Gotô family were left to the warrior class. The educated urban class discovered the fresh and unconventional Chinese “literati paintings” (bunjinga, 文人画) of the Southern Schools (nanshûga [南宗画] or short nanga [南画]) which had already been in the China a counter trend to the “professional painters” of the Northern Schools (hokushūga, 北宗画). This also brought in the rise of the machibori artists (町彫, “carvings of the townsmen”), a counter trend to the so far dominating iebori (家彫, lit. “hourse carvings”) of the Gotô school. Pioneers of the machibori trend were the artists of the Yokoya school (横谷) which hard freed themselves from their Gotô masters. This trend breathed new life into the world of sword fittings, not only in terms of motifs but also in terms of interpretation, combination of colours, and raw materials, and quite many of the great machibori masters were influenced by contemporary painters. Despite the general decline in quantity and quality of swords and sword fittings in the course of the post-Genroku financial difficulties, the machibori stimulus didn´t die down and reached another peak in the bakumatsu period and the transition to the Meiji era. Well, at the same time, the insecure bakumatsu period brought also a jolt towards practicability and simplicity and “back to good old values.” Thus some artists revived Muromachi period styles like of Nobuie. And with the opening of the country, the difficulties for craftsmen who worked in the sphere of the Japanese sword, new markets had to be tapped. One such market was the orientation towards a well funded Western clientel, but this market needed some adjustments as the greater part of customers couldn´t make a head or tail of wabi-sabi aesthetics. In this sense, most craftsmen working for the foreign market focussed on what was in demand, and that was a neat, picturesque, and floral ornamentation with the certain kitchy Japanese touch.

Picture 14: From Goto (left) to the new machibori trend (right two).

Picture 15: A machibori peak and the backwards orientation of the bakumatsu era.

Well, books can be written on each of these aspects but my aim was to provide an easy to understand historic overview of the development and changes of different Japanese aesthetics and their influence on tsuba as these “dots” are mostly not connected in relevant literature.

Many thanks for this, Markus. It is great to see a scholar actually connecting tsuba development to larger cultural contexts. This has long been a “complaint” of mine, as I think studying/appreciating tsuba outside of these larger contexts not only make little sense, but it will invariably lead to questionable conclusions/understandings. In particular, I am very happy to see you connect tsuba to Tea. For me, studying late-Muromachi and Momoyama Period iron tsuba without also studying/understanding Tea and its aesthetics is a pointless exercise. Thanks again.

Steve

Beautifully crafted articles