Whilst working on a longer article on Japanese sword exports to China during the Muromachi era, I found an interesting line in Táng Shùnzhi´s (唐順之, 1507-1560) Ode to the Japanese Sword (nihontô no uta, 日本刀歌) which lead me to further studies as I am waiting for a book to arrive from Japan to confirm certain parts of the article in question. Incidentally, we know several of such Odes to the Japanese Sword by Chinese authors, and the earliest is said to go back to the Song Dynasty Ōuyáng Xiū (欧陽脩, 1007-1072). Anyway, the line which attracted my attention was:

身上竜文雑藻荇

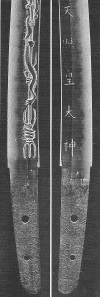

shinjô no ryûmon wa sôkô ni majiwaru “The dragon engraving on the blade is embedded in seaweed.”We know that Japan exported many swords to Ming China at the time of Táng Shùnzhi and most of them were made in the manufacturies of Osafune, and so I started to do some research on horimono from that time and region. First of all it has to be pointed out that contemporary records on swords made for export or the infamous „bundle swords“ hardly ever mention horimono, so most of the data we have goes back to actually extant pieces and some oshigata. The next thing that strikes is that elaborate and complex horimono on Osafune swords, i.e. not suken or bonji and the like, are very rarely found before the Meiô era (明応, 1492-1501) and concentrate on sword dated with the Bunki (文亀, 1501-1504) and Eishô eras (永正, 1504-1521). Just to recollect, the official and regulated trade (kangô-bôeki, 勘合貿易) with Ming China started in Ôei eleven (応永, 1404) and lasted in the mid 16th century when the system collapsed by independent contacts and trades of rich traders with Ming China and the Asian mainland as well as by the appearance of European competitors inthe East Asian waters. Also we observe that horimono in general and elaborate horimono like kurikara-ryû in particular are mostly found on Osafune blades which don´t mention the first name (zokumyô, 俗名) like „Yosôzaemon“ (与三左衛門), „Hikobei“ (彦兵衛) or „Genbei“ (源兵衛) and the like in their signatures. Of course there are some exceptions but experts agree that Osafune blades which mention the zokumyô in their signature are chûmon-uchi (注文打), i.e. made according to an order, whereat those just signed „Bizen no Kuni-jû Osafune“ (備前国住長船) followed by just the name of the smith, e.g. Sukesada (祐定), Kiyomitsu (清光), Tadamitsu (忠光), Katsumitsu (勝光) or Munemitsu (宗光), are by tendency rather kazuuchi-mono (数打物), mass produced swords, or so-called „tabagatana“ (束刀), „bundle swords“. One of the aforementioned exceptions for example is a blade by Yosôzaemon no Jô Sukesada dated Eishô 18 (永正, 1521) which shows a shin no kurikara on the omote and the characters „Kasuga Daimyôjin“ on the ura side (see picture 1).

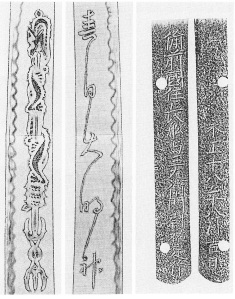

Picture 1: katana, mei: „Bizen no Kuni-jû Osafune Yosôzaemon no Jô Sukesada saku“ (備前国住長船与三左衛門尉祐定作) – „Eishô jûhachinen hachigatsu kichijitsu“ (永正十八年八月吉日, „on a lucky deay of the eighth month Eishô 18 [1521]“)

Let us stay with these names of deities for a while. I was able to find an article of Yokota Takao (横田孝雄) published in „Tôken-Bijutsu“ 493 (February 1998) in which he provides a quantitative survey on engraved names of deity on Sue-Bizen swords which goes as follows:

- Amaterasu Ômikami (天照皇大神): Katsumitsu, Munemitsu, Sukesada – The goddess of the sun and universe, the ancestor of all Japanese emperors, and the major deity in shintô.

- Hachiman Daibosatsu (八幡大菩薩): Katsumitsu, Munemitsu, Tadamitsu, Sukesada, Nagamitsu (永光) – The god of archery and war incorporating both elements from shintô and Buddhism.

- Namu Hachiman Daibosatsu (南無八幡大菩薩): Sukesada – Hail to Hachiman, the god of archery and war.

- Kasuga Daimyôjin (春日大明神): Sukesada – The numinous unit of the associated kami and buddhas/bodhisattvas of the Kasuga-Kôfukuji multiplex, Nara.

- Sumiyoshi Daimyôjin (住吉大明神): Katsumitsu, Sukesada – The collective of the four deities of the Sumiyoshi-jinja, Ôsaka, which were Sokotsutsu no Onomikoto (底筒男命), Nakatsutsu no Onomikoto (中筒男命), Uwatsutsu no Onomikoto (表筒男命) Okinagatarashihime no Mikoto (息長帯日).

- Kizuki Daimyôjin (杵築大明神): Sukesada – The collective of the deities worshipped in the Izumo-taisha (出雲大社), Izumo.

- Yaegaki Daimyôjin (八重垣大明神): Sukesada – The collective of the deities worshipped in the Yaegaki-jinja (八重垣神社), Izumo.

- Katte Daimyôjin (勝手大明神): Harumitsu (治光) – The collective of the deities worshipped in the Katte-jinja (勝手神社), Nara.

- Marishi Sonten (摩利支尊天): Katsumitsu, Munemitsu, Sukesada – Marici, the Deva or Bodhisattva associated with light and the sun, also supporting meditative practice to achieve a more heightened spiritual level. Bushi invoked Marishiten to achieve victory since Marici means „light“ or „mirage“, the female deity was invoked to escape the notice of one’s enemies.

- Marishiten no mikoto (摩利支天尊): Katsumitsu – A variant of Marici.

- Marishiten Bosatsu (摩利支天菩薩): Sukesada – Marici as Bodhisattva.

- Fudô Myôô (不動明王): Sukesada – Acala, a fierce guardian deity with a sword in the right hand which represents widsom and cutting through ignorance, and a lariat in the left hand with which he catches and binds up demons.

So with the mentioned observance in mind we can assume that elaborate horimono like dragons and the like were by tendency more applied to mass produced Osafune blades and that wealthy clients had, if at all, by tendency more simple horimono and/or the names of deities engraved. Unfortunately we hardly know any names of horimono-shi before the transition to the shintô era and the great carving masters coming from the school of Umetada Myôju (埋忠明寿). But we know a single name connected to Sue-Bizen horimono, namely those of „Matashirô“ (又四郎), the younger brother of Hei´emon no Jô Tadamitsu (平右衛門尉忠光) who was active around Eishô (永正, 1504-1521). This info goes back to a katana with the nagasa of 63,4 cm which is listed in my Index of Japanese Swordsmiths N-Z, p. 211, and which can be seen in picture 2. The mei reads: „Bizen no Kuni-jû Osafune Tadamitsu no ko Hei´emon no Jô kore o saku horimono otôto Matashirô saku“ (備前国住長船忠光子平右衛門尉作之彫物弟又四郎作, „work of Hei´emon no Jô son of Bizen Osafune Tadamitsu, horimono carved by his younger brother Matashirô“). The blade is dated „Eishô gannen hachigatsu-hi“ (永正元年八月日, „a day in the eighth month Eishô one [1504]“). Apart from this blade, the name of Matashirô only appears at one more blade (picture 3) which is signed: „Bizen no Kuni-jû Osafune Hei´emon no Jô Fujiwara Tadamitsu dô Matashirô kore o saku“ (備前国住長船平右衛門藤原忠光同又四郎作, „made by Hei´emon no Jô Fujiwara Tadamitsu and Matashirô from Osafune in Bizen province“), dated „Bunki ninen mizunoe-inu nigatsu kokonoka“ (文亀二年壬戌二月九日, „ninth day of the second month Bunki two [1502], year of the dog“). Well, it is assumed that this blade is not a joint work (gassaku, 合作) in the strict sense in terms of sword forging as we don´t know any (signed) blade made by a Matashirô Tadamitsu alone. So it is very likely that the blade in question is insofar a joint work as Hei´emon no Jô Tadamitsu forged it and his younger brother Matashirô engraved the horimono.

Picture 2: katana, mei: „Bizen no Kuni-jû Osafune Tadamitsu no ko Hei´emon no Jô kore o saku horimono otôto Matashirô saku“ (備前国住長船忠光子平右衛門尉作之彫物弟又四郎作) – „Eishô gannen hachigatsu-hi“ (永正元年八月日).

Picture 3: katana, mei: „Bizen no Kuni-jû Osafune Hei´emon no Jô Fujiwara Tadamitsu dô Matashirô kore o saku“ (備前国住長船平右衛門藤原忠光同又四郎作) – „Bunki ninen mizunoe-inu nigatsu kokonoka“ (文亀二年壬戌二月九日)

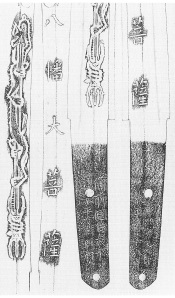

Picture 4: katana, mei: „Bizen no Kuni-jû Osafune Jirôzaemon no Jô Fujiwara Katsumitsu“ (備前国住長船次郎左衛門尉藤原勝光) – „Asakaze“ (朝風, „morning wind“, the nickname of the blade) – „Matsushita Masatoshi shoji“ (松下昌俊所持, „owned by Matsushita Masatoshi“)

Than there is a blade from the very same year and month, i.e. eighth month Eishô one, made by Jirôzaemon no Jô Katsumitsu (次郎左衛門尉勝光) (see picture 4) which shows almost identical horimono. Thus it is assumed that they too were engraved by Matashirô. And then there is a very similar kurikara-ryû found on a blade by Hei´emon Tadamitsu from the eight month Eishô one, but which was made when he stayed in Innoshô (院庄) in Mimasaka province as it is mentioned on the tang. Even when we take into consideration that the eight month might not point out the month the blade was actually made (as stated in one of my previous articles), it is still rather unlikely that Matashirô accompanied his brother to Mimasaka province and engraved at the same time horimono to blades of Jirôzaemon no Jô Katsumitsu. Because modern horimono-shi also say that even if you take into consideration the working conditions of that time, it still took probably a month or so to engrave such an elaborate kenmaki-ryû. So it is likely that Matashirô was the head of a specialized workshop which just did horimono and maybe various hi. And the craftsmen under his command surely used the sketches of the master and engraved them as faithfully as possible onto blades for which horimono were ordered.

So far this little excursus to the world of Sue-Bizen horimono and a lengthy article on the Japanese sword exports to Ming China will follow after receiving reference material from Japan.