With a focus on Sôtatsu, Kôetsu, and Myôju

When I was in DC over the Thanksgiving weekend, it goes without saying that I visited the ongoing Sôtatsu: Making Waves exhibition at the Freer and Sackler Galleries. Outstanding works of art from a time in Japanese history which I like very much, especially as my favorite tsuba maker and one of my most favorite Japanese artists were active then, Umetada Myôju (埋忠明寿) and Hon’ami Kôetsu (本阿弥光悦). Back home, I was once again going through some of my earlier drafts to remember how they all, i.e. Sôtatsu, Kôetsu, and Myôju were connected and whilst I was bringing together and restructured half-finished articles, I thought I better post the result on my site rather than leaving it, again, hidden somewhere on my HD. In this sense, I would like to proceed by introducing each of the artists for himself and working out their relation at the end of each corresponding section. But first of all, I would like to introduce an artwork from the exhibition which impressed me the most, and which is not even by Sôtatsu himself (it is from his studio).

It has the brief title Trees and is a pair of six-panel folding screens that depicts a variety of evergreen trees lined up across a gold-foil ground, to quote from the catalog. One of the screens is filled with trees whilst of the other more than half is left empty, leaving just the golden ground as decorative element. The trees are interpreted in a very realistic manner and even if the emphasis is on presenting the widest variety of evergreens, they go so perfectly together as if you are standing in front of a forest that naturally grew that way. You just have to see it in person, that means from the distance it was meant to be appreciated, namely in a dimly lit room with the gold acting as intensifier for each and every light source and being so to speak a true successor of the grandeur of the Momoyama era (the screens are dated to the Kan’ei era [1624-1644] by the way). That means, the decorative effect is kept but the realistic interpretation already goes in a different direction, away from the bold interpretations of the Momoyama era. For a better understanding of the art, and of paintings of the Momoyama era in particular, you must not only focus on what was going on at that time but you also have to look back. In the Kamakura period, painting had been very much influenced (and commissioned) by the clergy, or had been narrative, but the China-orientation of the Ashikaga-bakufu during the Muromachi period created a boom in secular paintings depicting just landscapes, the four seasons, trees or flowers for example, all of that primarily drawn from trigger words of Chinese legends. In the course of this development, painters eventually started to go “fully secular” towards the end of the Muromachi period. For example, screens with not just legendary Chinese but with concrete Japanese sites appeared that were made for not more and not less than admiring domestic beauties of nature. Of course, the effect of many of these paintings was intensified with the help of Japanese sentiments, i.e. a solitary pine on a rock was not just a beautiful pine but alluded to loneliness. You get the picture. This impressionistic approach runs like a continuous thread through all of Japan’s high art anyway, first by formulated scenes from the classics, later merely by allusions.

Then the chaos of the Sengoku era was ended by Nobunaga and his successor Hideyoshi and a phase of prosperity and extraordinary amount of construction took place. That means, when Nobunaga finally ended all the mess that was going on due to the power vacuum left by a weakening to virtually non-existing Ashikaga-bakufu (and local hegemons getting stronger and stronger, trying to come into power) and Hideyoshi continuing his policies, people, especially in Kyôto, felt that this might be peace after all. I mean, Hideyoshi’s campaigns to unify the country were still going on until 1590 but that concerned first and foremost the more remote regions like Kyûshû and Kantô. At the same time, the mentioned local hegemons constructed enormous castles and residences to underline their status, capability and wealth, and this is especially true for Hideyoshi and his projects in and around Kyôto. In addition, Nobunaga and Hideyoshi have sponsored renovations and reconstructions of countless palace and religious facilities to get as an exchange court titles and lands. And all this lead to a unprecedented number of patrons who were more diverse than ever before. Now not only the bakufu employed artists like that of the Kanô and Tosa Schools were thriving but independent artists were able to get a foot in the door and that more or less just on the basis of their talent (and the ability to sell oneself of course).

Chinese Lions, Kanô Eitoku, Imperial Household Collection, Late 1580s

Landscape with the Sun and Moon, jûyô-bunkazai, unknown artist, mid-16th century, Kongôji (Ôsaka Prefecture)

It has to be mentioned that the course was basically dictated. That is, all the golden screens and paintings with their prima facie easy-to-grasp ornamentation were born to a certain extent out of the need to create artworks that are visually perceptible and appreciable from a certain distance for the ever growing rooms and halls. One of the greatest trendsetters was, of course, an established, prestigious painter from one of the main lines, Kanô Eitoku (狩野永徳, 1543-1590), who had the honor of working directly for Nobunaga and Hideyoshi. But even Eitoku, see picture above, referred to extant interpretations like for example to the early Muromachi period Landscape with the Sun and Moon screens from the Ôsaka Kongô-ji that already introduces some gold (see bottom picture above, and don’t compare the two screens directly, just their aesthetical concept). So as indicated, the ornamental path was kind of laid out, i.e. the Momoyama artists did not start to paint in that ornate way out of the blue, but it was the unique background of peaceful and thriving Momoyama-era Kyôto that created such a highly fascinating momentum in Japanese art history. And this does not only apply to paintings but also two sword fittings. One of the first (and probably the most famous) of the new and independent, that means non-bakufu employed painters, was Hasegawa Tôhaku (長谷川等伯, 1539-1610). Tôhaku was a professional painter from Noto province who moved to Kyôto to study under the Kanô School and when his contemporary Eitoku died in 1590, he found himself as official painter for Hideyoshi. His most representative “Momoyama Kanô-style” work is shown below. Well, many many books have been written on each of these artists and aspects and I tried to break down the background of the Momoyama era (visual) art world as much as possible for the introduction to this humble article.

Maple, kokuhô, Hasegawa Tôhaku, 1592/93, Chishaku’in (Kyôto)

*

Tawaraya Sôtatsu

And with this we arrive at Tawaraya Sôtatsu. Surprisingly little is known on the person Sôtatsu for an artist of his influence (three of his works are designated as kokuhô for example). First of all, we don’t know when he was born and when he died but as his son and successor Sôsetsu (宗雪) was granted with the honorary Buddhist title of Hokkyô in Kan’ei 19 (1642), a title that had been granted before to his father, it is assumed that Sôtatsu had either died shortly before or retired and died shortly later as Sôsetsu moved for good to Kanazawa the following year. The first time Sôtatsu appears in written history is when he was repairing famous late Heian sutra scrolls for Fukushima Masanori (福島正則, 1561-1624) in Keichô seven (1602). Masanori was at that time the daimyô of the Hiroshima fief of Aki province and the scrolls, that were preserved in the local Itsukushima-jinja, so to speak under his jurisdiction. So Masanori paid for the repair work but did not go to Kyôto himself to pick a fan painter (more on that soon) to work on “his” treasured scrolls. It was the Kanô school painter Kaihô Yûshô (海北友松, 1533-1615) and favorite of Hideyoshi and Emperor Go-Yôzei (後陽成天皇, 1571-1617) who had travelled to the Itsukushima-jinja in 1598 to study the famous scrolls. So it was him who “convinced” Masanori to have them repaired and it is safe to assume that it was him too who suggested a capable artist to go with for this project. Anyway, we know that Sôtatsu ran the Tawaraya (俵屋) at that time, a painting shop that – unlike the large, bakufu and court serving Kanô studio – focused on ready-made objects. The Tawaraya, Sôtatsu’s family name was Nonomura (野々村) by the way, was first and foremost a fan shop but also sold smaller art objects like hanging scrolls and poetry sheets. Back then, quite an importance was attached to fans. They were a fashion accessory that not only demonstrated style but to a certain extent also social status and the very mood at that day. They were also perfect gifts as their decorations often bear subtle messages, transported through visual quotations from classical literature, narratives of war, and romance, to use again words from the catalog to the Sôtatsu exhibition. With the Tawaraya’s customer base in mind, i.e. the local machishû (町衆), the Kyôto upper class to put it simply, it is understandable that artistic objectives were set very high. I mean, these customers were well-versed in art and the classics and to not hold up to ridicule among their circles, they were only going for the best of the best. We don’t know much about the ventures of Sôtatsu in the first two decade of the 17th century but we do know from records that at the latest by Genna two (1616), Emperor Go-Mizunoo (後水尾天皇, 1596-1680) was aware of the work produced by the Tawaraya. Also we know that Sôtatsu had became a very close friend of courtier, poet, and painter Karasumaru Mitsuhiro (烏丸光広, 1579-1638) by then and it is assumed that it was Mitsuhiro who provided all the good connections. It is unclear when Sôtatsu had fully arrived in court circles but usually the Genna era (1614-1625) is quoted in this respect. In 1630, he received the aforementioned honorary title of Hokkyô, a great and unusual honor for an “outsider” artist like him and by then, he had virtually became a court painter, carrying out commissions for the highest of the highest clientele.

*

Hon’ami Kôetsu

Kôetsu (see picture above) was born in Eiroku one (1558) into the prestigious Hon’ami family of sword appraisers and sword polishers to the bakufu. The Hon’ami lineage into which Kôetsu was born, the Kôji (光二) lineage, was primarily working for the wealthy Kaga Maeda family, receiving impressive 200 koku per year. Kôetsu however, the second generation of the relative young Kôji lineage, did not focus that much on swords but turned out to be an allround artist and besides calligraphy, he was a passionate potter, a lacquer artist, publicist, and follower of the tea ceremony, mastering each of these arts entirely. By the way, it is assumed that he had passed on all his professional sword obligations to his adopted son-in-law Kôsa (光瑳, 1574-1637) who succeeded as third generation Kôji-Hon’ami. When it comes to painting, there is the theory that Kôetsu has been a student of the aforementioned Kaihô Yûshô and that it was the latter who introduced him to Sôtatsu. Like it is the case with Sôtatsu, Kôetsu’s exact connections remain to a certain part unknown but what we do know is that he was independent by nature, and a versatile genius with an unfailing sense of taste. So whilst Kôetsu was strengthening his cultural and business relations in Kyôto in the decade after Sekigahara, Ieyas was about wiping out the remaining important members and abiders of the Toyotomi clan. And when he finally did so by capturing Ôsaka Castle in 1615, he offered Kôetsu an official position in the bakufu for 300 koku per year, 100 koku more than the Maeda were paying him. But Kôetsu declined with thanks as he avoided going to Edo by all means as the new and hardly developed capital was then totally uninteresting for an artist like him. As “compensation,” Ieyasu granted him a plot of land, Tagamanine (鷹峯), located on the northern outskirts of Kyôto and on the northeastern slopes of Mt. Daimonji (about 5 miles from present-day Kyôto Station). Well, there are now two approaches to explain this gift: One says that it was really a gift of Ieyasu, the lands of yielded later decent 176 koku per year and had tax exempt status. But the other one says it was more like an exile to keep Kôetsu out of Kyôto politics because Ieyasu did not fully trust him. One of Kôetsu’s close friends namely, tea master and warrior Furuta Oribe (古田織部, 1544-1615), had just been forced to commit seppuku because of his alleged loyalty to the Toyotomi so everyone with whatsoever ties to this family was treated by Ieyasu with suspicion. Anyway, Kôetsu turned Takagamine into an artist community with a relative strong religious touch, housing more than 200 residents and also agricultural fields. Incidentally, the records differ on the size of Takagamine and either list 30 or 25 ha for the entire plot. Invited to live there and provided with a house were for example Kôetsu’s paper and brush makers, makie artists, members of his own family and of the Hon’ami main line, and the wealthy draper Ogata Sôhaku (尾形宗伯, 1570-1637) who had excellent relations to the Imperial family and who also was Kôetsu’s nephew. Sôhaku’s father Dôhaku (道伯) was married to Kôetsu’s older sister and his grandson Kôrin (光琳, 1658-1716) went down in history as name giver of the Rinpa School (琳派) of painting. Sôtatsu’s collaboration basically took place before the establishment of Takagamine but some of the last joint artworks date 1615 or shortly after. Recent studies strongly suggest that both artists must have worked simulatenously in a session or at least very closely together on these artworks, the famous scrolls with the gold and silver paintings (by Sôtatsu) and poems (by Kôetsu). (I have used one of them, the Crane Scroll, which is pre-1615 by the way, as cover for my book on the Hon’ami family.) Incidentally, we find on the map of the allocations of the houses in Takagamine the name of the weaver Hasuike Tsuneari (蓮池常有) of whom some assume that he was somehow related to Sôtatsu. Reason for this assumption is that Sôsetsu’s successor of the Tawaraya, Sôsetsu (相説), was from the Kitagawa family (喜多川) and the Kitagawa were a branch of the Hasuike.

Takagamine as seen in the Miyako Meisho Ezu (都名所絵図, 1780)

*

Umetada Myôju

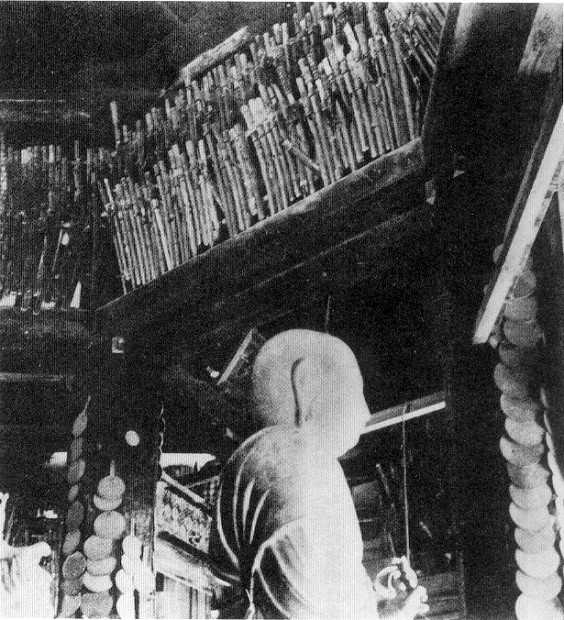

Myôju was born in the same year as Kôetsu, Eiroku one (1558), and his family too was working on a hereditary basis for the bakufu. The Umetada were not only swordsmiths but also made certain sword fittings and were also responsible for arranging koshirae. That means, the Umetada received the blade from the smith, or in the case of an old blade from the customer, and the tsuba and the other sword fittings from the tsuba and sword fittings maker respectively, for instance from other prestigious bakufu-employed lineage like the Gotô (as far as sword fittings like mitokoromono are concerned). In a next step, the Umetada first equipped the blade with a new habaki as the habaki has to be tailor-made to the blade and as a proper saya can not be made before the blade has a tailor-made habaki. The tsuba was adjusted to the blade either by punches around, or by inserting soft-metal pieces on top and bottom of the nakago-ana. The wood and lacquer work and the hilt wrapping and so on was commissioned to family members or sub-contracting craftsmen and the Umetada family had, depending on the specification of the customer, more or less artistic freedom in arranging the koshirae. And then there were two important task which connected the Umetada to the Hon’ami family. One was the shortening of blades, and the other one was to inlay (in gold or silver) the attribution of a sword the Hon’ami had forwarded them on its tang. We know from records that the Umetada family also dealt with swords, or bought up “hidden treasures” to submit them to the Hon’ami for authentication and attribution – the kinzôgan-mei carried out in the own workshop of course – to sell them later for five times the purchase price for example. So the two families were pretty closely linked. But back to Myôju. We don’t know for sure when and how he came in touch with Kôetsu but we can try to guess what was going on. Myôju started his career as a swordsmith and the earliest extant dated swords are from Keichô two (1597), from a time when he signed with “Muneyoshi” (宗吉). He was already 40 years old at that time. Also we learn from a signed sword by one of his master students, Hizen Tadayoshi (肥前忠吉), that when Tadayoshi came to Kyôto to learn from the Umetada in Keichô one (1596), still Myôju’s father Myôkin (明欽) was the head of the family. The name change to “Myôju” took place two years later, in Keichô three (1598), and it is assumed that this was the time when he took over the forge. But then something odd happens, that is, a gap of almost ten years from which no swords are known. The next known dated blade after the Keichô three one is from Keichô twelve (1607). I mean, there was Sekigahara going on just two years after his succession as Umetada head and there was thus surely a need for newly made swords. Well, it is possible that he was forced to produce in masses for a certain time and to deliver the majority of these blades unsigned as it was customary for fulfillments of bakufu orders. But after everything had calmed down, we are still facing a gap of at least five or six years and this phase of “unproductiveness” seems rather odd for a master swordsmith like him. Now we know that he handed over the management of the Umetada forge and workshop to his younger brother Jusai (寿斎) some time during the Keichô era (1596-1615) and everything points towards that he did so to have more time to cultivate his contacts with the then Kyôto art world. At this point it has to be mentioned that there are outstanding tsuba extant by Myôju that really take up the unique style of the Momoyama era (see picture below) and thus we may assume that he gave up the forge right after Sekigahara to focus for several years on developing a very special kind of tsuba. It has to be mentioned that Myôju was also a great engraver (horimono-shi) and that he trained several craftsmen in this art who turned out to become masters themselves. In other words, Myôju was well versed in working with steel and soft metal, in performing gold inlays, and he knew how to guide a chisel.

tsuba with oak motif, jûyô-bunkazai, mei “Umetada Myôju,” Momoyama era, brass with a slightly raised shakudô hira-zôgan ornamentation and ko-sukashi, owned by the Hôeidô Corporation

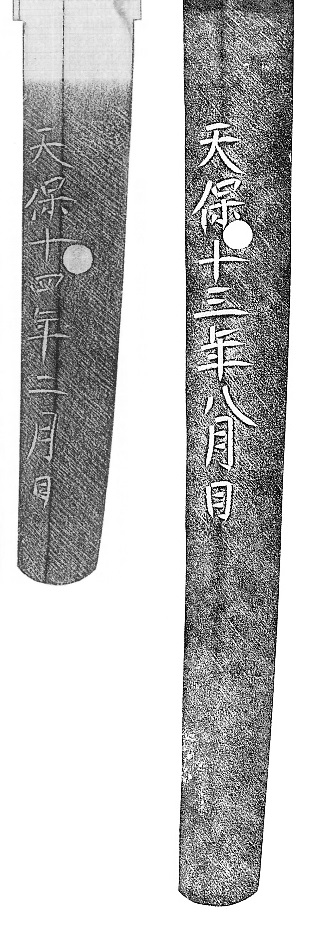

Now how does Myôju go in line with Takagamine? Well, Kôetsu and Myôju knew each other pretty well, that is from their related jobs and from the fact that they both lived in Kyôto and moved in the local machishû circles. And by the way, the Hon’ami residence was just across the Horikawa-dôri from the Nishijin district where the Umetada workshop was located, i.e. just a stone’s throw away. It is unclear if Myôju made all of his Momoyama-style tsuba in the “ten year break” from sword forging or if he made them at the side until the end of his career. The year after the break, i.e. 1608, must have been a busy one as far as sword forging is concerned as about one third of all known dated blade goes back to that year. Also we know that his training of horimono-shi concentrated on the later years of the Genna era (1615-1624). Apart from that, he never gave up sword forging because there exists a blade, a ken, that was made just two months before his death, which was in Kan’ei eight (1631) by the way (Kôetsu died six years later in Kan’ei 14, 1637).

A very interesting entry is found on an extant map of Takagamine that mentions all the house owners of the community. Therein we find a certain “Umetada Dô’an” (埋忠道安) who lived in the town house directly opposite from the residence of Kôetsu (see detail below). Now the name Dô’an does not appear in any of the Umetada genealogies but experts assume that it is either an otherwise unknown pseudonym of Myôju or that a very close family member of Myôju lived in that house. The former approach, i.e. Dô’an being a pseudonym of Myôju, is explained by the religious orientation of Takagamine. We know that Kôetsu was a faithful Nichiren (Hokke) follower and that he also acted as a spiritual leader of the artist community. At that time, “Dô” (道) was a popular character to form one’s Hokke name from and it is possible that Dô’an was the lay name of Myôju that he used in Takagamine after Kôetsu had “convinced” him to follow the religious orientation of the community when residing in Takagamine.

Detail of the Takagamine map: (1) Residence of Kôetsu, (2) townhouse of Dô’an, please note that the name is quoted as “Mumetada Dô’an” (むめたゝ道安).

*

What an exciting time the Momoyama era was for the Japanese art world! I want to deal with Takagamine in more detail at some time in the future and apart from that, I want to dedicate Umetada Myôju one day a book within my series that focuses on certain artists, i.e. in the style of my publications on Kanô Natsuo and Masamune.