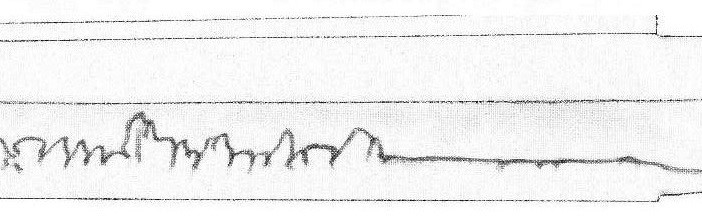

Judging the hamon and the bôshi are the third step in kantei, the final step which allows one – in the ideal case – to identify the smith or at least the school. The hamon and bôshi are quite individual factors. Of course, this result of the Japanese approach in making blades that leaves a visible hardening pattern was initially purely functional but soon, the variations and activities that occur along this hardening pattern and which developed from technical improvements left scope for individuality. Again, as this series is on kantei, I want to leave out the metallurgical and technical aspect of the hamon and want to focus on what is visible. First of all, we distinguish between if the hardening is straight or undulating and refer thus to the two main types of a suguha (直刃) and a midareba (乱刃) respectively. According to the actual outline of the hamon, the latter type, i.e. the midareba, is further subdivided into a notareba (湾れ刃・のたれ刃, large waves), gunomeba (互の目刃, larger roundish elements), chôjiba (丁子刃, smaller clove/tassel-shaped elements), or tôranba (濤瀾刃, surging waves). Apart from that, there is the so-called hitatsura (皆焼) where large areas of the blade are hardened. A hitatsura can be based on a notareba, gunomeba, or even a chôjiba, so this term does not refer to a specific hamon outline. All these main and sub types are further differentiated and named according to their interpretation and these differentiations/names will be described later.

*

3.1 Nie and nioi

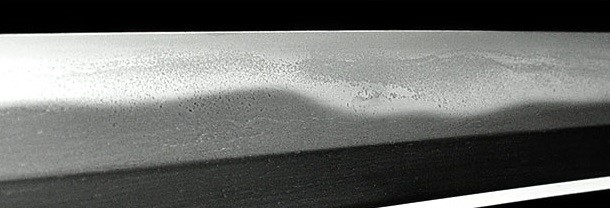

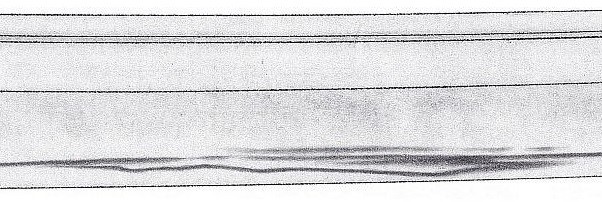

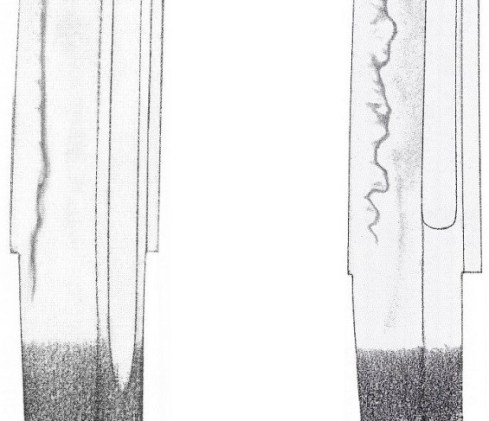

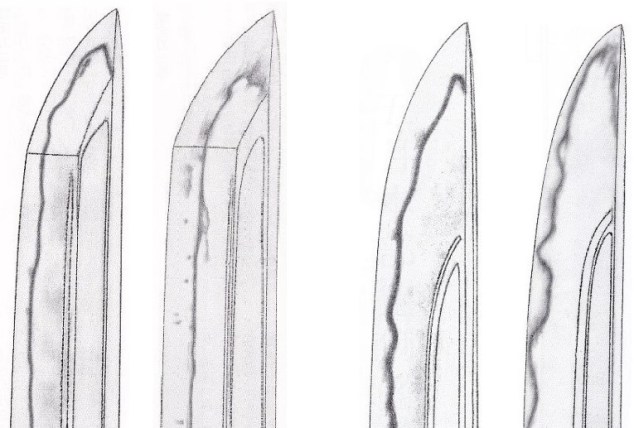

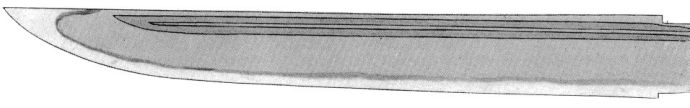

I would like to start with another, quite important factor that must be taken into account, and that is the question of hardening, or to be precise, the question of what crystalline effect is left visible due to the hardening. Here too, we distinguish between two main types, nie (沸) and nioi (匂), which are identical from a metallurgical point of view (both being of martensite) but differ in terms of visible effect. In other words, a swordsmith can harden a blade in a way that leaves larger, i.e. visible martensite crystals, nie, or in a way where the martensite crystals are so fine that no individual particles can be made out, nioi. Of course, there is also an intermediate condition which is referred to as ko-nie (小沸). And if the visible, that means the nie crystals are large and rough, we speak of ara-nie (荒沸) (see picture below), or if there are really obvious patches of large nie also the term kazunoko-nie (鯑沸・数の子沸, lit “herring roe nie”) exists but which is mostly reserved to describe the visible nie activities of Satsuma-shintô smiths. And irregular accumulations of nie are called mura-nie (叢沸) whereas ara-nie and mura-nie as well as in some cases also kazunoko-nie might not be intended by the smith and testify to poor craftsmanship. Incidentally, there is also the term hadaka-nie (裸沸, lit. “naked nie”) which describes single, isolated and mostly dark and somewhat larger nie, a feature that is usually associated with Suishinshi Masahide (水心子正秀). Back to nie and nioi in general. To distinguish between these two basic kinds of hardening, the terms nie-deki (沸出来) and nioi-deki (匂出来), or nie-hon-i (沸本位) and nioi-hon-i (匂本位), respectively have become standardized vocabulary. Please note that the term “ko-nie-deki” is not much in use at all.

ara-nie

Next I want to focus on the border of the hamon, i.e. the area where the hardened edge (yakiba, 焼刃) ends and the unhardened ji (地) begins. This border is called habuchi (刃縁) or nioiguchi (匂口) regardless of if the hardening is in nioi or in nie-deki. Well, to be precise, habuchi is the more neutral term for the border of the hardened edge whereas the term nioiguchi was born from the fact that there are always nioi at the border of a hamon, i.e. there is no such thing that the hamon goes over to the ji with nie only. Or in other words, there might be plenty of nie but they are always embedded into nioi along the habuchi, thus the term nioiguchi. With this we arrive at how to address the amount of nie/nioi and the condition of the nioiguchi. Plenty of nie are usually described as nie-atsushi (沸厚し) or nie-fukai/fukashi (沸深い・沸深し), although the former is more used to refer to the presence of ji-nie. Please note that the term nie-atsushi means literally “thick nie” but it refers just to the amount and not to the size of the nie crystals. And thick nioi, what automatically means a wide or deep nioiguchi, are referred to as nioi-fukai/nioi-fukashi (匂深い・匂深し). The opposite of a wide nioiguchi is a tight nioiguchi for which the term nioi-shimaru (匂い締まる) is used. Apart from that, the nioiguchi can be bright (akarui, 明るい) and clear (saeru, 冴える) or be dull/hazy or subdued (shizumu, 沈む) or look soft (yawarakai, 柔らかい) or weak (yowai, 弱い) respectively. The brightness of the habuchi or nioiguchi alone can be a good indicator for the school or smith, for example the early Osafune mainline smiths like Nagamitsu (長光) and Kagemitsu (景光) or the Kanbun-shintô smith Kotetsu (虎徹) are known for hardening a very bright nioiguchi. And the other way round, a subdued nioiguchi might either point towards a rural school or smiths who stuck to an early, classical workmanship, e.g. earlier Kyûshû and Hokkoku smiths. A noticeably wide nioiguchi speaks for shintô in general, or for Ôsaka-shintô and Hizen in particular. But again, characteristic approaches in how the nioiguchi is interpreted will be pointed out in the later chapters. Not to forget, don’t mix up the nioiguchi with the hadori polish! That means you have to look at the blade under a proper light condition so that the actual border of the yakiba shows itself and you not only look at the (cosmetic) course of where the hadori was applied.

In conclusion it must be said that apart from merely recognizing the nioiguchi to draw conclusions on a possible school or smith, there is also the point of view of technical and artistical skill and quality. That means, a bright and clear and first of all consistent nioiguchi is desirable and shows that the smith was adequately skilled. So if the nioiguchi varies considerably and “unnaturally” in width and/or brightness, it is a sign that the smith lacked skill and that you are not facing a work of one of the top masters. The same applies as indicated above to an irregular, unnatural presence of nie. In the following, I want to do it the same way as with the jigane/jihada, that means as we are on the topic of nioiguchi, I first introduce in alphabetical order all major hamon hataraki and conditions as most of them anyway focus along the habuchi, before going over to the different outlines/interpretations of the hamon.

*

3.2 Hataraki and conditions of the hamon

abu no me (虻の目) – Lit. “horsefly eyes.” Closely arranged, roundish yakigashira seen along certain gunome-midare interpretations of the 2nd generation Hizen Tadahiro (忠広). The area resembles a pair of compound eyes, thus the name.

ashi (足) – A thin line of nioi that runs across the hamon towards the cutting edge. Ashi were first introduced to straight hamon patterns to limit the maximum size of a lateral crack of the yakiba to the distance between two ashi. In other words, a crack usually does not exceed an ashi because it is of a somewhat softer steel structure than the yakiba. According to the interpretation of ashi, a distinction is made between: nezumi-ashi (鼠足, lit. “rat’s legs”), very small ashi; ko-ashi (小足), small ashi; naga-ashi (長足), long ashi; chôji-ashi (丁子足), chōji-shaped ashi; gunome-ashi (互の目足), gunome or zigzag-shaped ashi; nie-ashi (沸足), ashi composed of nie; saka-ashi (逆足), ashi slanting upwards (i.e. towards the kissaki); and Kyô-saka-ashi (京逆足), ashi slanting downwards (i.e. towards the nakago).

fushi (節) – Lit. “bamboo node(s).” Pointed knot-like breaks in a straight hamon. Often seen on blades by Mino smiths.

ginsuji (銀筋) – Basicaly the same as kinsuji but slightly duller in color, thus the name ginsuji (silver line/string). However, the differentation of kinsuji and ginsuji is not clear but in old sword publications, ginsuji are often associated with Kagemitsu (景光).

hakikake (掃掛け) – Lit. “sweeping.” Similar to sunagashi, but much shorter and thinner and spilling into the ji. Can appear along the habuchi of a hamon and/or in a bōshi.

hotsure (ほつれ・解れ) – Arrangement of nie which make the habuchi look like a frayed piece of cloth. Also called nie-hotsure (沸ほつれ・沸解れ).

ika no atama (烏賊の頭) – Lit. “squid heads.” Wide and noticeably protruding elements, sometimes even up to the shinogi, along flamboyant and slanting hamon interpretations of the Fukuoka-Ishidō smiths Koretsugu (是次) and Moritsugu (定次) that remind of the head of a squid, thus the name.

imozuru (芋蔓) – Lit. “potato vines.” Thick and conspicious inzuma appearing in the habuchi and hamon which are a very typical feature of Satsuma-shintō and Satsuma-shinshintō blades.

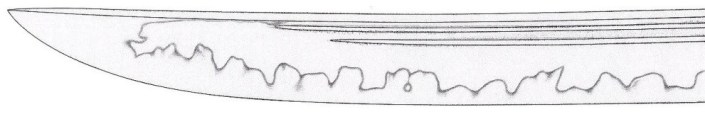

inazuma (稲妻) – Lit. “lightning.” Crooked kinsuji which resembles a bolt of lightning.

kani no te (蟹の手) – Lit. “crab hands.” Special gunome-midare inter-pretation with split yakigashira that protrude alternatingly to the left and right and which remind thus of crab claws. Please note that the term kani no te is used to refer to this feature when seen on Sue-Seki blades. In the case of Sue-Bizen works, the term kani no tsume (蟹の爪, lit. “crab claws”) has become established even if the same feature is described.

kinsuji (金筋) – Lit. “gold line.” A short, straight, brilliant black line of nie that appears inside the hamon, usually near the habuchi. If crooked, the term nazuma (稲妻) is applied.

koshi (腰) – The “hip” (koshi) of a hamon element. Raising part that follows the tani (谷), the “valley” of a hamon element, ending in the “head,” the yakigashira (焼頭).

koshiba (腰刃) – A singular or a few high rising temper element(s) in the habaki area. A koshiba is sometimes also referred to as Mino-yakidashi (美濃焼出し).

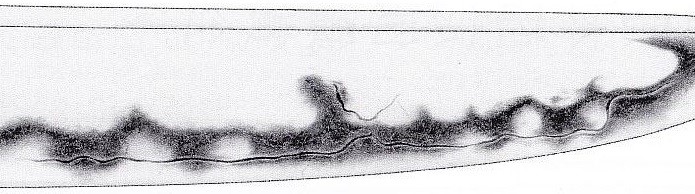

kuichigai-ba (喰違い刃) – Area of a hamon where the habuchi splits with the upper habuchi running over a noticeable distance more or less parallel and with a gap to the lower habuchi.

kuwagata-ba (鍬形刃) – Hamon interpretation of for example the Yamashiro smith Nobukuni (信国) where two yakigashira protrude in a long manner to the left and to the right into the ji, remotely resembling the kuwagata crest on a samurai helmet.

kuzure (崩れ) – Crumbling, deformed part of a nie-based hamon, usually seen at a midareba. Also referred to as nie-kuzure (沸崩れ) or yaki-kuzure (焼き崩れ).

muneyaki (棟焼き) – Hardened areas along the back of a blade.

nie-sake (沸裂け) – Lit. “torn nie. ” Bright, black nie along a hamon which make the habuchi look like as if has been torn apart. This feature is similar to kuichigai-ba but shorter and more frayed.

nie-suji (沸筋) – Lines of nie running parallel to the hamon.

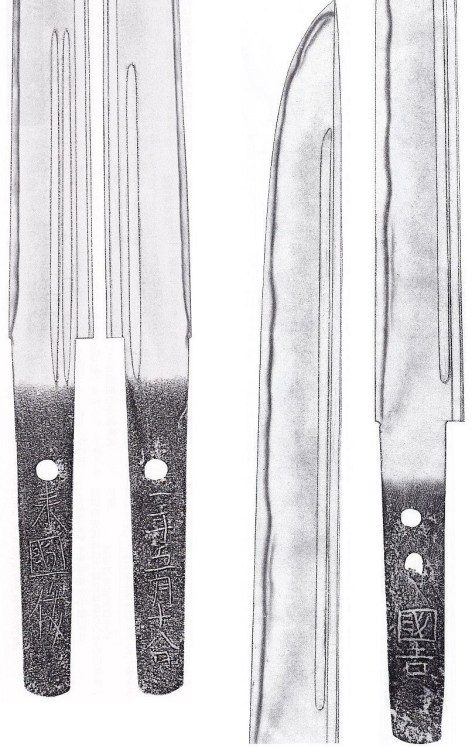

nijūba (二重刃) – Lit. “double ha.” A second habuchi line, consisting of nie or nioi, drawn parallel to the main habuchi.

sanjūba (三重刃) – Lit. “triple ha.” A habuchi with two additional habuchi lines, consisting of nie or nioi, drawn parallel to the main habuchi.

sunagashi (砂流し) – Lit. “stream of sand” or “flowing sand.” Accumulation of nie that resembles the marks left behind by a broom speeping over sand. Sunagashi usually appear inside the hamon and near and parallel to the habuchi.

tobiyaki (飛焼き) – Lit. “flying hardening (elements).” Hardened spots in the ji which are not connected to the hamon.

uchinoke (打除け) – A short nijūba directly over the habuchi that resembles a crescent moon. Usually seen on suguha-based hamon and/or blades forged in masame, e.g. on works of the Yamato Tegai school (手掻).

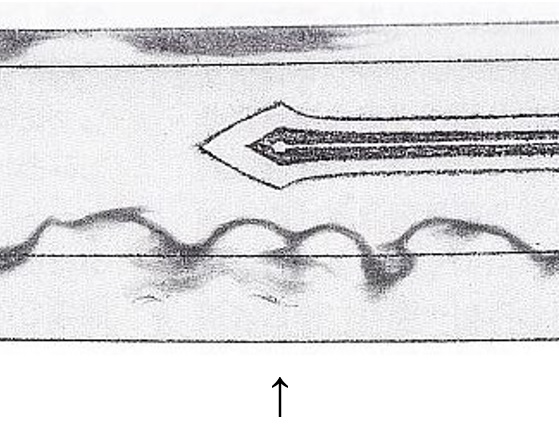

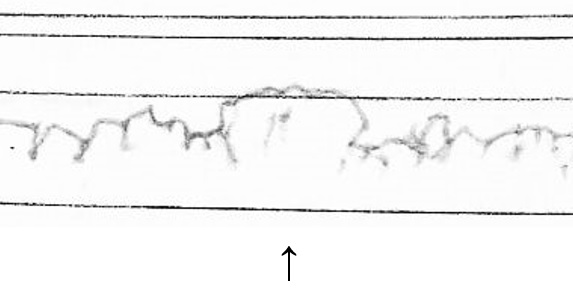

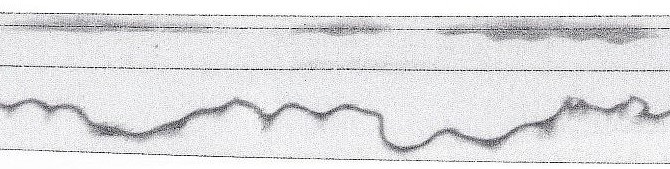

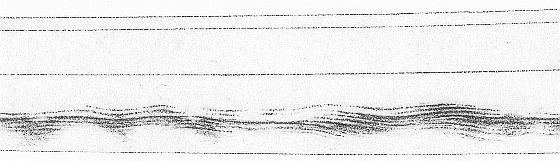

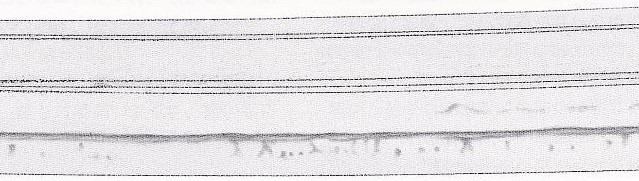

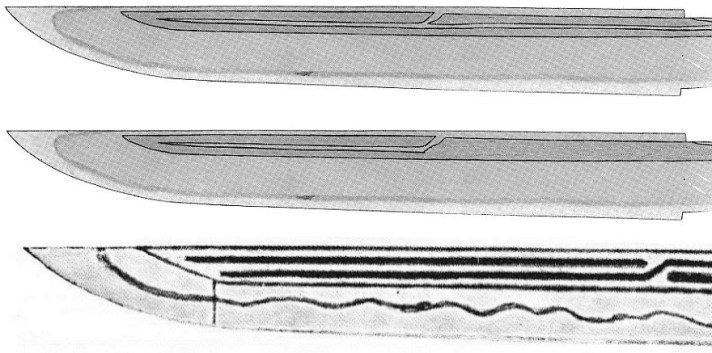

yakidashi (焼出し) – The beginning of a hamon around the ha-machi. At unshortened blades, the hamon usually runs a little bit into the tang. There are different interpretations of this starting of the hamon and we basically distinguish between the following forms: sugu-yakidashi (直刃焼出し), straight start which turns after a more or less short distance into the “actual” hamon; Ōsaka-yakidashi (大坂焼出し) (see picture below top), also starts straight or as gentle notare but the yakiba widens smoothly to turn into the “actual” hamon; Kyō-yakidashi (京焼出し) (see picture below bottom), the yakiba starts in suguha but turns then rather abruptly into the “actual” hamon; Mino-yakidashi (美濃焼出し), the yakiba starts with a koshi-ba (see koshi-ba); Satsuma-yakidashi (薩摩焼出し), term to refers to Satsuma-shintō blades where the hamon starts like at most kotō blades right away as midareba.

yakikomi (焼込み) – Prominent single hamon element right over the ha-machi or yokote.

yaki-otoshi (焼落し) – Lit. “fallen/dropped hardening.” Term to describe when a hamon does not start around the ha-machi but more or less noticeably later on the blade. It is often seen on very early blades and on blades that have been retempered.

yō (葉) – Lit. “leaf.” Ashi that is separate from the habuchi and that appears scattered inside the hamon. In past-Muromachi times, also the term nioi-kuzure (匂い崩れ) was used to describe this effect.