Rai Kunitoshi was succeeded by his son Kunimitsu (国光) who took over an already very much flourishing Rai School. Well, as so often when talking about such relative early smiths, there are several traditions extant, like that he was actually the younger brother, grandson, or mere a student of Kunitoshi but the widely accepted one is that he was straightforward his son. As for his active period, we know date signatures from Karyaku one (嘉暦, 1326) to Kan’ô two (観応, 1351) and the Kôsei Kotô Meikan introduces a dated blade from Shôwa two (正和, 1313). However, we can assume that he was mostly engaged assisting his father at that time, as daimei works from the first two decades of the 14th century show. Rai genealogies, historic documents, and certain blades (and signatures, more on this later) furthermore suggest that there was a second generation Kunimitsu, but we can’t say for sure when the shift of generations took place. The Kotô Meizukushi Taizen says that the first generation Kunimitsu was born in Bun’ei one (文永, 1264) and died Shôkyô four (正慶, 1335) at the age of 72 but odd here is that the Shôkyô era only counted brief two years. Maybe the author mixed up the then partially overlapping and double counting of nengô eras of the Nanbokuchô era. Anyway, the source also says that the second generation was active around Kôei (康永, 1342-1345) and this approach is also followed by several experts, e.g. Satô Kanzan. Tanobe sensei in turn thinks that the differences in workmanship and signature style of the later works dated with Jôwa (貞和, 1345-1350) and Kan´ô (観応, 1350-1352) might just go back to the advanced age of the master, i.e. that there was maybe just one generation Kunimitsu. But when we take into consideration that his greatest masterworks are dated somewhere around Karyaku (嘉暦, 1326-1329) and Gentoku (元徳, 1329-1331) and assume on the basis of that he had achieved full artistic maturity at that time, it really seems as if the blades made 20~25 years later go back to the hand of a successor. So, to recap: I think that Kunimitsu took over the Rai School pretty soon after the third year of Gen’ô (元応, 1321) as this is the last known dated blade of his father who was then already 82 years old. In case he was the biological son of Kunitoshi, he was already a fully trained master smith at the height of his career at the time he became the newly appointed head of the forge (remember, Kunitoshi was born in 1240). Thus he was able to continue without interruption to satisfy the exquisite customer base of Kunitoshi, therefore the masterwork output right after his succession. In other words, there was no “experimental” post-succession phase which gradually leads to artistic maturity, no, Kunimitsu took the reins being already an undisputed Rai grandmaster. He also ranks about equal to his father Kunitoshi when it comes to designations by the Agency of Cultural Affairs and the NBTHK, 26 in terms of the former (3 kokuhô and 23 jûyô-bunkazai), and slightly over 200 (about 180 jûyô and more than 20 tokubetsu-jûyô) in terms of the latter category.

Now to Kunimitsu’s workmanship, beginning again with long swords. Kunimitsu did make some classical and slender tachi with a ko or rather a smallish chû-kissaki but the majority shows a more or less elongated chû-kissaki and a mihaba that does not taper that much and as stated in some of the previous posts of this kantei series, I am a sugata guy and this is for me a key element in distinguishing him from Kunitoshi. In short, his tachi are just overall more magnificent and wide and give us some idea of what is coming, and that is the heyday Nanbokuchô trend to overall larger blades. No wonder, was most of his career taking place in the Nanbokuchô period anyway (i.e. Rai Kunimitsu was active from the very end of the Kamakura to the beginning of the mid-Nanbokuchô period). However, it is interesting to see that his signed blades are by trend from the more classical and elegant camp but this again is insofar actually not that odd as the wider and more magnificent blades were all of a longer nagasa too and got therefore shortened (and lost their mei).

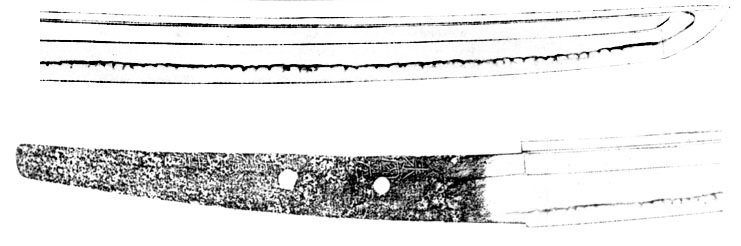

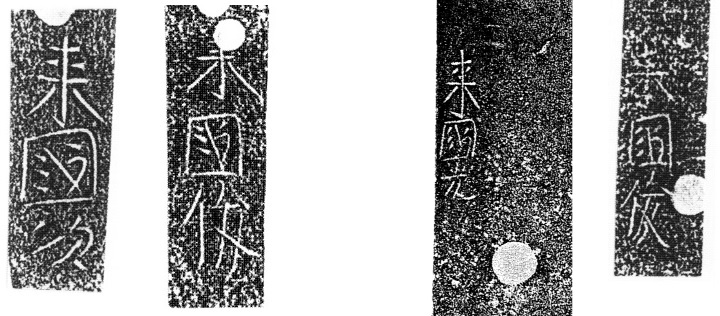

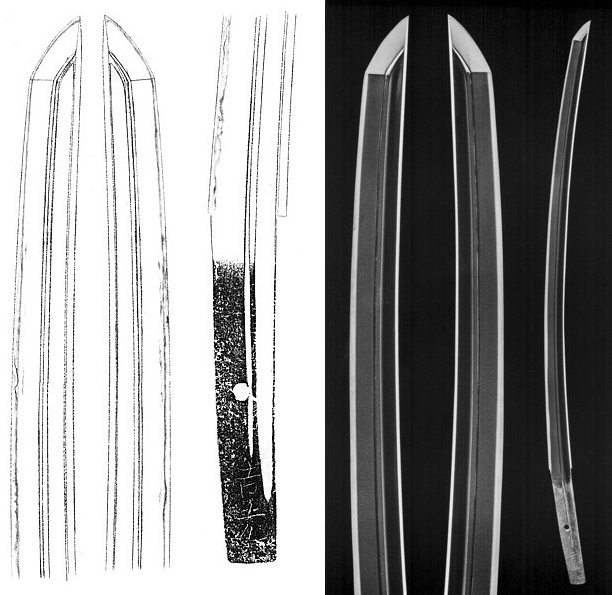

Let me start with some of the signed works, with the most representative ones the two tachi that are designated as kokuhô (the third kokuhô is a tantô and will be introduced later). One is completely ubu and is dated in kakikudashi manner, a feature that is also seen at his father Kunitoshi, with “Karyaku ninen nigatsu hi” (嘉暦二年二月日, “a day in the second month Karyaku two [1327]”). The blade (see picture 1) has a normal mihaba, a deep toriizori with funbari, and a straightforward chû-kissaki, i.e. it maintains with the deep curvature and the noticeable taper still a certain elegance. The kitae is a very fine ko-itame with plenty of ji-nie and the hamon is a ko-nie-laden hiro-suguha-chô that is mixed all over with ko-chôji, ko-gunome, plenty of ashi and connected yô, and some kinsuji. The nioiguchi is rather tight and the bôshi is a widely hardened sugu with a hint of notare and a ko-maru-kaeri. A bôhi is engraved on both sides that ends in kakudome at the machi. This is by the way the only known dated long sword of Rai Kunimitsu.

Picture 1: kokuhô, tachi, mei “Rai Kunimitsu – Karyaku ninen nigatsu hi” (来国光 嘉暦二年二月日), nagasa 78.8 cm, sori 3.6 cm, motohaba 3.6 cm, sakihaba 1.9 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, preserved in the Tôkyô National Museum

The other signed kokuhô is seen in picture 2 and this one is suriage. This was once a very long blade as its shortened nagasa is still 80.6 cm! It shows a deep toriizori and a chû-kissaki and as it does not taper that much like the previous blade, it looks overall more magnificent and stout, i.e. with the chû-kissaki almost a little bit like ikubi at a glance. The kitae is a very dense ko-itame mixed with some masame and plenty of ji-nie. This blade and the previous one do not show any areas of weak or so-called Rai-hada. The hamon is a ko-nie-laden suguha-chô mixed with ko-midare, ko-chôji, ko-gunome, plenty of ashi (mix of ko, chôji, and gunome-ashi), and yô. Please note that the hamon of this blade is sometimes described as hiro-suguha but it is in my opinion not that wide to pass as hiro. The bôshi is sugu with a ko-maru-kaeri and this time, the bôhi ends due to the shortening in marudome in the tang. Again, please remember that this blade had once a nagasa of over 90 cm! Some more info on it can be found on my “sister site” here.

Picture 2: kokuhô, tachi, mei “Rai Kunimitsu” (来国光), nagasa 80.6 cm, sori 3.3 cm, motohaba 3.0 cm, sakihaba 2.2 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune, preserved in the Kyûshû National Museum

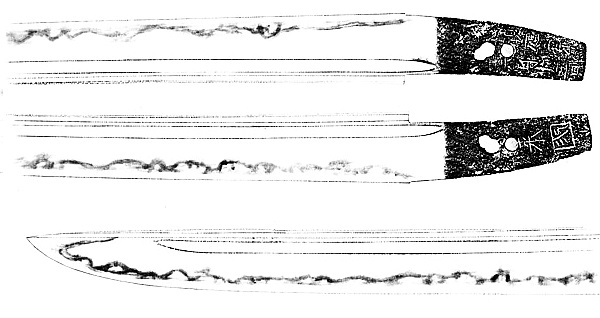

As you can see in the oshigata to blade 1, the hamon is truly interpreted as suguha-chô, i.e. running straight but mixed with an abundance of ko-chôji and ko-gunome or rather with chôji-ashi and gunome-ashi for most of the time. But Rai Kunimitsu also worked in pure suguha, or to be more precise, in a somewhat undulating suguha, i.e. not in a perfectly straight suguha as for example seen on a Hizen blade. The blade shown in picture 3 is a good example for this field of his repertoire and I picked it not only because I had the opportunity to study it hands on but because it it shows two important characteristic features of Rai Kunimitsu, and that is isolated sections of njûba and brief kuichiga-ba. And not to forget, it also shows a feature that distinguishes him from Rai Kunitoshi, namely that his ha comes with a somewhat tighter and more “defined/precise” habuchi. The blade has a magnificent and wide sugata that so to speak anticipates the later grandeur from the heyday of the Nanbokuchô era and the kitae is this time a somewhat standing-out itame that is mixed with mokume and that is not as tightly forged as at the two kokuhô. It also shows plenty of ji-nie and a nie-utsuri. The hamon is as mentioned a suguha in ko-nie-deki that tends overall a little to notare and is mixed with ko-ashi and some nijûba towards the yokote. The bôshi is sugu with a ko-maru-kaeri and kuichigai-ba and both sides bear the so to speak “obligatory” Rai Kunimitsu bôhi that runs due to the ô-suriage as kaki-tôshi through the tang. Incidentally, the blade was once a heirloom of the Owari-Tokugawa family and Hon’ami Kôchû issued (in Genroku three, 1690) an origami for it, giving it a value of 500 kan.

Picture 3: tokubetsu-jûyô, katana, mumei “Rai Kunimitsu” (来国光), nagasa 73.6 cm, sori 1.6 cm, motohaba 3.1 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

Let’s talk about another typical interpretation from the oeuvre of Rai Kunimitsu, demonstrated via the katana shown in picture 4. This time the hamon is still a ko-nie-laden suguha-chô but which mixed with shallow but conspicuous notare waves. Apart from that, it is mixed with ko-gunome, ko-chôji, plenty of ashi and yô, muneyaki, and with some fine kinsuji and sunagashi. And with the appearance of hotsure, uchinoke, nijûba, and yubashiri and with the sugu-bôshi that shows hakikake and that runs out as yakitsume, we can even grasp a hint of Yamato. But the steel is different from Yamato and appears as very dense, fine, and beautifully forged ko-itame with ji-nie that truly speaks for Kyô.

Picture 4: jûyô, katana, mumei “Rai Kunimitsu” (来国光), nagasa 71.8 cm, sori 2.6 cm, motohaba 2.85 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune

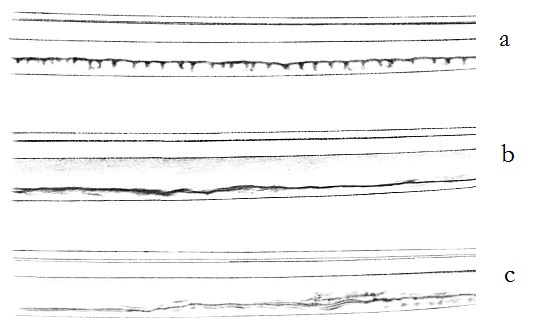

Before we continue with Rai Kunimitsu’s tantô, let me first repeat his three basic long sword styles and second, address the sensitive point of Rai-hada. One of his basic styles is the suguha-chô that is mixed with ko-chôji and ko-gunome or rather with chôji-ashi or gunome-ashi (picture 5 a). The other basic style is an almost pure suguha with just some ashi or slanting Kyô-saka-ashi and a little nijûba and/or kuichigaiba (picture 5 b). And the third one is an undulating suguha that shows horizontal, layered, “yamatoesque” hataraki (that remind if you want a little bit of Rai Kuniyuki) (picture 5 c).

Picture 5.

As for Rai-hada, this is a feature which I would typically place with Rai Kunimitsu right away, or in other words, it is seen at Kunitoshi sometimes but hardly at all at Kunitsugu what means if you can make out Rai-hada on a blade that you can nail down as Rai main line work (i.e. obviously no Rai offshoot like Ryôkai or Enju) somewhere from the very end of the Kamakura to the early Nanbokuchô, I would recommend going for Kunimitsu right away. Now those weaker areas of Rai-hada usually appear for long swords somewhere from the monouchi to the yokoto, and for tantô often right where the grooves end, i.e. again more in the upper area. And apart from that we can say that this feature is generally more often seen on tantô than on tachi (at least as far as Rai Kunitoshi is concerned).

*

This brings us to Rai Kunimitsu’s tantô where we see again a wide variety of interpretations, for example classical ones in standard size, wider ones, wider and longer ones in sunnobi-style, and even a couple in kanmuri-otoshi-zukuri, with the majority showing either a katana-hi or some other kind of horimono like gomabashi or suken (or both, i.e. gomabashi on one, and a suken on the other side). This means, we can not name one specific tantô style for Rai Kunimitsu. First I want to introduce the third kokuhô of Kunimitsu (see picture 6), and that is the meibutsu Uraku Rai Kunimitsu (有楽来国光), named after the fact that it had once been owned by Sen no Rikyû’s master tea student Oda Urakusai Nagamasu (織田有楽斎長益, 1547-1622). More info here. The blade is with a nagasa of 27.7 cm rather on the long side and is wide and thick but maintains an uchizori, i.e. the thickness of the kasane and the presence of uchizori as well as the nagasa being just not long enough tells us that we have still not arrived yet in the heyday of the Nanbokuchô period. Incidentally, the blade is dated around Karyaku (1326-1329). The kitae is a fine ko-itame with chikei and plenty of ji-nie and we also seem some Rai-hada here and there. The hamon is a wide and nie-laden notare mixed with gunome and ashi and comes with a wide and very bright and clear nioiguchi. The bôshi is a prominent midare-komi with a rather pointed and long running-back kaeri. The entire bôshi is quite nie-laden and tends with its kuzure to kaen. The blade is vigorous and powerful and as the mihaba is wider than usual and the hamon shows much midare, the blade can be mixed up with a work of Rai Kunitsugu at a glance but the wild bôshi shows the hand of Kunimitsu. That is, Kunitsugu did often harden a vivid midareba but it usually runs into a relative calm bôshi in notare with a ko-maru-kaeri whereas at Kunimitsu the bôshi is mostly emphasized.

Picture 6: kokuhô, tantô, mei “Rai Kunimitsu” (来国光), nagasa 27.7 cm, uchizori, motohaba 2.7 cm, hira-zukuri, mitsu-mune, the blade is owned by the NBTHK

Picture 7 shows one of the two Kunimitsu tantô that are interpreted in kanmuri-otoshi-zukuri. It is designated as a jûyô-bunkazai and is also a meibutsu, namely the Ikeda Rai Kunimitsu (池田来国光) as it was once owned by Ikeda Sanzaemon Terumasa (池田三左衛門輝政, 1564-1613). The blade is rather wide, muzori, and shows again a thick kasane. The kitae is a dense and very uniformly forged ko-itame with ji-nie that does not show any weak areas of Rai-hada and apart from that, we see the Rai-typical nie-utsuri which focuses on the fukura/monouchi area. The hamon is a nie-laden shallow notare that is mixed with ko-gunome, ashi, yô, and kinsuji and the bôshi is slightly undulating, widely hardened, shows hakikake, and runs back in a long manner.

Picture 7: jûyô-bunkazai, tantô, mei “Rai Kunimitsu” (来国光), nagasa 26.3 cm, muzori, motohaba 2.5 cm, kanmuri-otoshi-zukuri, mitsu-mune

Now these two tantô have shown pretty much midare so let me introduce next an interpretation in suguha. The blade shown in picture 8 comes in a sunnobi-sugata, i.e. it is long and wide, but still does not show any sori and features a relative thick kasane. The kitae is a densely forged ko-itame with plenty of ji-nie, much fine chikei, and a nie-utsuri. The hamon is a slightly undulating, ko-nie-laden suguha that is mixed with ko-ashi, fine kinsuji and sunagashi, and along the monouchi with some nijûba. The nioiguchi is bright and clear and the bôshi appears as slightly widening sugu with a ko-maru-kaeri. Now the nijûba elements might make one think of Awataguchi Kuniyoshi or Yoshimitsu but at the former, the nijûba would be much more prominent and appear in longer connected sections, and from the latter, we would expect that the ha gets thinner along the fukura. In addition, we would expect some connected ko-gunome and more nie-hataraki in the bôshi on a Yoshimitsu tantô but apart from that, the horimono are anyway too far from the mune for an Awataguchi work.

Picture 8: jûyô, tantô, mei “Rai Kunimitsu” (来国光), nagasa 29.15 cm, muzori, motohaba 2.8 cm, hira-zukuri, mitsu-mune, this blade was once presented by shôgun Tokugawa Tsunayoshi (徳川綱吉, 1646-1709) to Iechiyo (家千代, 1707), the second son of his adopted son Ienobu (徳川家宣, 1662-1712) who had died at the age of only two months .

As mentioned, Kunimitsu also made some classical tantô, for example the jûyô-bunkazai seen in picture 9. This blade has a so-called standard nagasa (jôsun) of 24.5 cm, uchizori, and is with the curved furisode-style nakago pretty conservative. It shows a fine ko-itame with plenty of ji-nie and a nie-utsuri and the hamon is a very bright and clear chû-suguha in ko-nie-deki that features a rather tight nioiguchi and a ko-maru bôshi with a long kaeri. The work is elegant and noble and reminds of his father Rai Kunitoshi.

Picture 9: jûyô-bunkazai, tantô, mei “Rai Kunimitsu” (来国光), nagasa 24.5 cm, uchizori, hira-zukuri, mitsu-mune, the blade was once owned by the Akimoto (秋元) family, the daimyô of the Tatebayashi fief

*

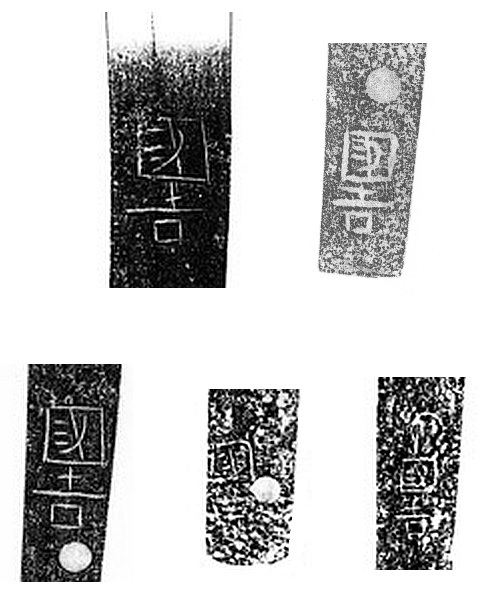

What about that 2nd generation Rai Kunimitsu? As indicated at the very beginning of this chapter, it is possible that the shift of generations took place somewhere around Kôei (康永, 1342-1345). When it comes to distinguishing features, many sources take the quality route, i.e. they say that late Rai Kunimitsu blades which are somewhat inferior in overall quality and which show a more smallish and thinly chiseled signature might be works of the second generation. That quality aspect is defined by a hamon that lacks both hataraki and that tight nioiguchi that is typical for Rai Kunimitsu and a kitae where the ko-itame stands more out and is mixed with some nagare and masame and which shows a hint of shirake rather than a nie-utsuri. Also possible supplements in the mei like “Yamashiro no Kuni-jû” (山城国住) or “Sahyôe no Jô” (左兵衛尉) are said to be associated with the second generation.

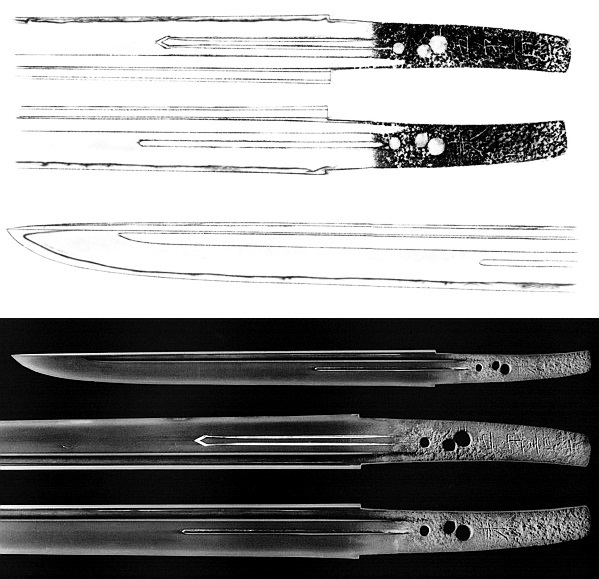

I want to introduce two blades which bear the latest known date signature of Rai Kunimitsu. Both are tantô and the first one is signed “Rai Kunimitsu – Kan’ô ninen rokugatsu” (来国光・観応二年六月, “sixth month of the second year of Kan’ô [1351]”) (see picture 10). It has a nagasa of 25.9 cm, is rather wide, has only a hint of sori, and features a thick kasane. Please note that this tantô has an iori-mune, what is uncommon as Rai Kunimitsu usually made tantô with a mitsu-mune. The kitae is a densely forged ko-itame that is mixed with some itame here and there and that shows ji-nie, fine chikei, and a faint nie-utsuri. The hamon is a bright and clear chû-suguha in ko-nie-deki that is mixed with some ashi, yô, and fine sunagashi. The bôshi is sugu with a little notare and turns back (on the omote) with a somewhat “awkward” ko-maru-kaeri (the ura shows a normal ko-maru-kaeri) but which is seen sometimes at tantô of Rai Kunimitsu. When introduced by the NBTHK in their kantei series, there was no mention of a second generation having a hand in this one and although not labelling it explicitly “Nidai” in the jûyô paper, we find the remark it “might be a work o the second generation when we follow the traditional classification via date signatures.”

Picture 10: jûyô, tantô, mei see above, nagasa 25.9 cm, a little sori, motohaba 2.6 cm, hira-zukuri, iori-mune

The second one (see picture 11) is signed “Rai Kunimitsu – Kan’ô ninen rokugatsu jûsannichi” (来国光・観応二年六月十三日, “13th day of the sixth month Kan’ô two [1351]”). The sugata and tang finish are about identical to the previous work and this one is labelled by the NBTHK as “Nidai” in their jûyô paper. The blade is a little longer but features a rather thin kasane (and again a mitsu-mune), and the hamon is not suguha but notare-chô mixed with gunome, ashi, yô, and sunagashi. It is a little suriage so that only the upper part of the character for “mitsu” is left and interesting here is that the date signature is chiselled in two rows.

Picture 11: jûyô, tantô, mei see above, nagasa 28.2 cm, sori 0.2 cm, motohaba 2.7 cm, hira-zukuri, mitsu-mune

Then there is this tantô shown in picture 12 which is dated “Jôwa sannen rokugatsu ichinichi” (貞和三年六月一日, “first day of the sixth month Jôwa three [1347]”) and which is introduced by Satô Kanzan as “early work of the second generation.” It is with a nagasa of 24.8 cm somewhat smaller and has an overall rather classical sugata. The kitae is an itame-nagare with many weak areas and shirake and the hamon is a suguha in ko-nie-deki that is mixed with some shallow notare and sunagashi. The nioiguchi is bright and clear and the bôshi is sugu with a standard ko-maru-kaeri.

Picture 12: tantô, mei “Rai Kunimitsu” (来国光), date see text above, nagasa 24.8 cm, a hint of uchizori, hira-zukuri, mitsu-mune

And last but not least one of the very few long swords that I was able to find which might well be a work of the second generation. It is a tachi bearing an orikaeshi-mei that was once an ôdachi measuring somewhere around 90 cm. It was shortened to 71.4 cm, has a rather wide mihaba, despite the suriage a relative deep sori, and an elongated chû-kissaki. The kitae is a standing-out itame mixed with some nagare and ji-nie appears. The hamon is a shallow ko-notare in ko-nie-deki that is mixed with ko-midare, gunome, ko-chôji, plenty of ko-ashi, sunagashi and kinsuji. The bôshi is a shallow notare-komi with a very brief ko-maru-kaeri and features nijûba. So probably the distinct midareba in combination with the somewhat inferior kitae and the smallish mei are the most important features for attributing this blade to the second generation.

Picture 13: jûyô, katana, orikaeshi-mei “Rai Kunimitsu” (来国光), nagasa 71.4 cm, sori 2.25 cm, motohaba 3.1 cm, shinogi-zukuri, iori-mune