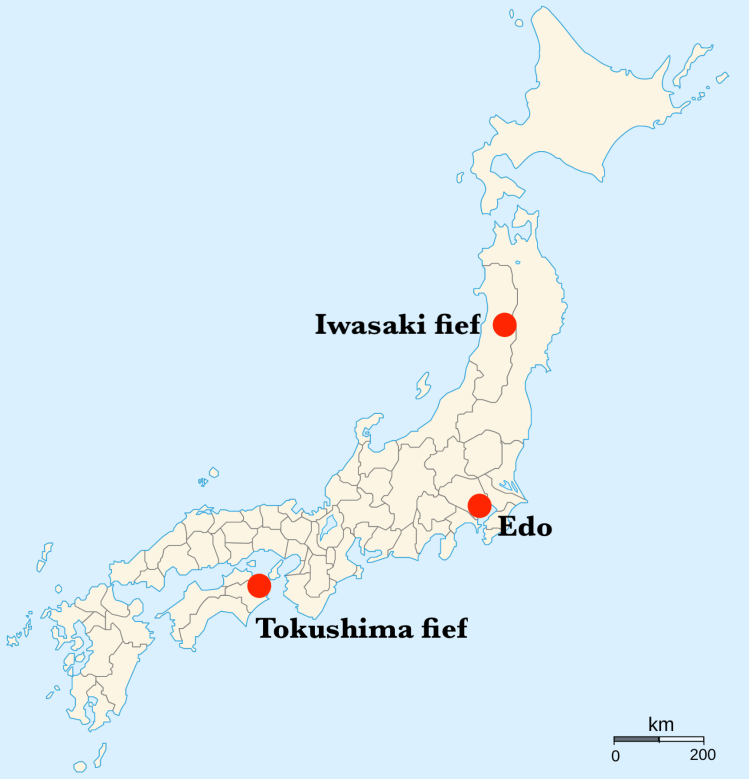

The title of this short article is not really catchy, but I didn’t want to say “yet another interesting blade” again. In any case, what got the ball rolling, if you will, is the blade shown in picture 1 below, a wakizashi made by a little known local swordsmith, but more on this later, because as always, I would like to start with some historical background.

Picture 1: Wakizashi, mei: Ishikawa Masanao saku (石川正直作), kinzōgan-mei: Horie Okinari + kaō (堀江興成「花押」). Nagasa 40.0 cm, sori 1.2 cm.

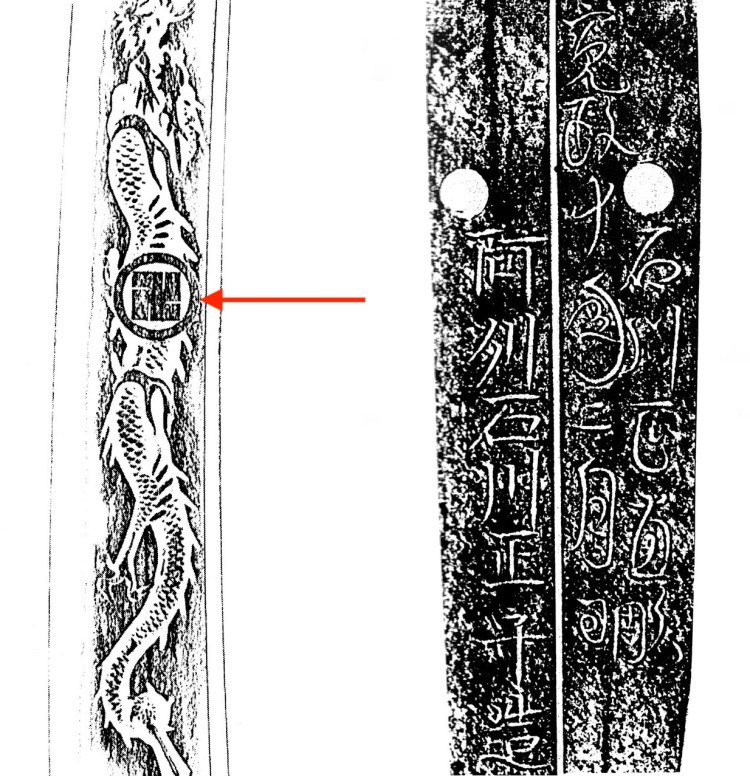

For a better understanding of the context, we have to go back to the summer of Hōreki four (宝暦, 1754). Hachisuka Yoshihisa (蜂須賀至央, 1737–1754), then only 17 years old and holding the office of ninth Daimyō of the Tokushima fief (徳島藩) in Awa province on Shikoku for less than two months, was about to die. As he had no son yet, he adopted on his deathbed Satake Yoshisue (佐竹義居, 1738–1801), the fourth son of the Daimyō of the quite distant Iwasaki fief (岩崎藩) in Dewa province, Satake Yoshimichi (佐竹義道, 1701–1765) (Picture 2). So, Yoshisue found himself as newly fledged Daimyō being himself only 16 years old (or 17, according to the then Japanese way of counting one’s age), adopting the name Hachisuka Masatane (蜂須賀政胤). All this took place in Edo, not in Awa province, which Yoshisue/Masatane visited for the first time in the fourth month of Hōreki five (1755) after having his genpuku ceremony and having changed his name one last time to Hachisuka Shigeyoshi (蜂須賀重喜) (Picture 3).

Picture 2: Map with relevant places.

Shigeyoshi entered his rule at a time when after the affluent Genroku era (元禄, 1688–1704), the Shōgunate and most of the fiefs realized they had to tighten their belts. With the eighth Tokugawa Shōgun Yoshimune (徳川吉宗, 1684–1751) at the forefront, it was a time of widespread reforms all across the country. Accordingly, also Shigeyoshi wanted to improve the financial situation of his fief. He initiated a barrage of measures, with one of them being the patronage of the arts and crafts in order to stimulate his economy.“Good for us,” Shigeyoshi had a fondness for swords and sword fittings. So, what he did was sending some of his most promising swordsmiths to Edo to study with masters like Suishinshi Masahide (水心子正秀, 1750–1825) and Ozaki Suketaka (尾崎助隆, 1753–1805), one of them being the maker of the blade in question shown in picture 1, Ishikawa Masanao (石川正直).

Picture 3: Hachisuka Shigeyoshi.

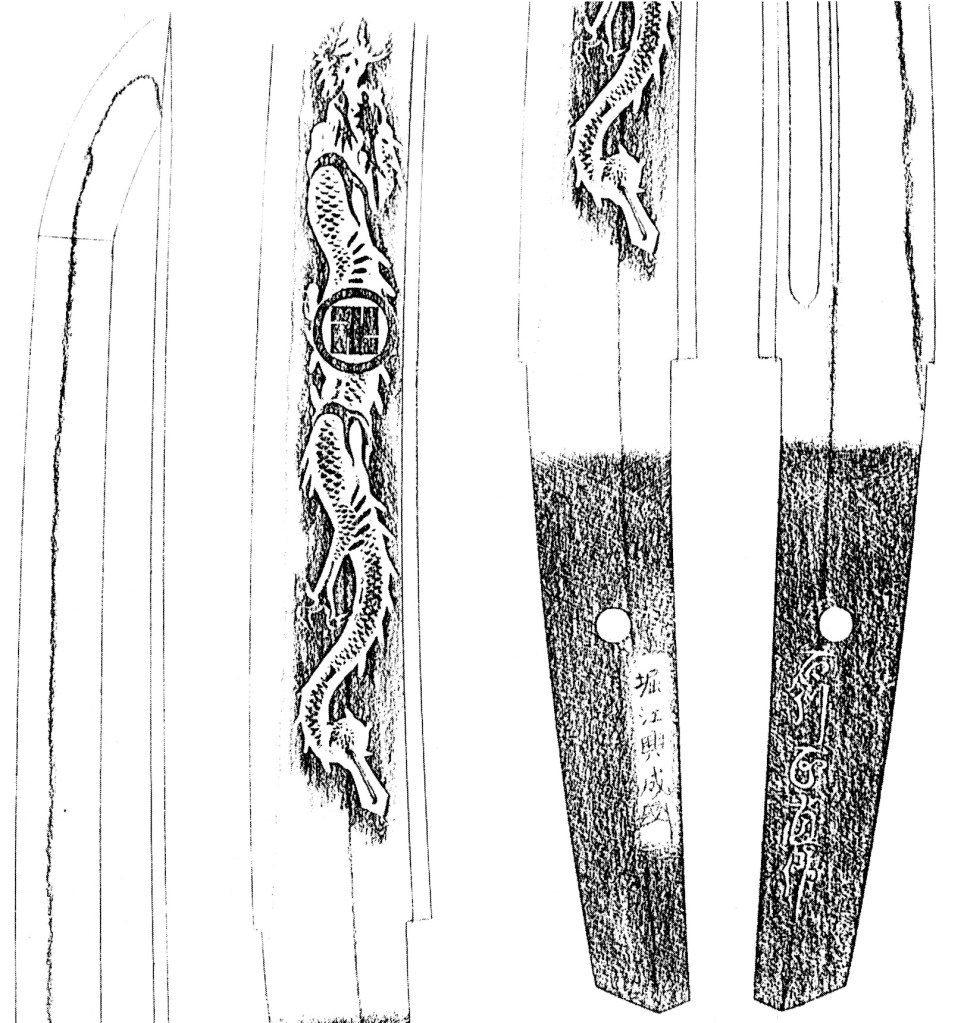

Masanao had made said blade after his stay with Suishinshi Masahide and had presented it to his Daimyō Shigeyoshi, who is said to have cherished it a lot. I also want to point out a nice little detail: The dragon horimono on the omote side of the blade bears centrally the encircled swastika crest of the Hachisuka family (Picture 4, left). Also, it is safe to assume that Masanao had engraved the horimono himself as a gassaku (joint work) between him and his father (or older brother, depending on the source) Ishikawa Masamori (石川正守) exists, which is inscribed: “Ashū Ishikawa Masamori tsukuru – Kansei jūnen nigatsu hi, Ishikawa Masanao horu” (阿州石川正守造・寛政十年二月日、石川正直彫) – “Made by Ishikawa Masamori from Awa province on a day of the second month Kansei ten (1798), engraved by Ishikawa Masanao” (Picture 4, right).

Picture 4

All that said, what caught my attention with this blade is the fact that it bears the kinzōgan-mei “Horie Okinari + kaō” (堀江興成「花押」). Some of you might have heard this name as Horie Okinari (?–1844?) was a famous Kinkō master, who had trained with Hamano Shōzui (浜野政随, 1696–1769), with the Ōmori (大森) School, and with Ozaki Naomasa (尾崎直政, 1732–1782). What ties everything together is that Okinari was also employed by the Hachisuka family, as part of said patronage in order to stimulate the economy of the Tokushima fief. Even if Shigeyoshi was removed from power relatively early in his rule, more on this in a second, I tend to think that Okinari was hired by Shigeyoshi himself. Reason for this assumption is that Shigeyoshi gifted the very blade introduced in this article at some point to Okinari, who is said to have inlaid his name and monogram in gold on the tang himself. Or, the gift came later by the retired Shigeyoshi as a reward for the longstanding service Okinari provided for the fief.

Anyhow, we have here another case where a sword (or a sword fitting) can unravel so much historical context, if you dig. Research of this kind, and provenance research in general, is a part of my service that I really enjoy, and I encourage everyone who has a Japanese arms and armor object that is engraved/inscribed with a name to dig, and I don’t say that as a shameless business plug!

All that said, I would like to conclude with narrating the remainder of Hachisuke Shigeyoshi’s life. As indicated, he was removed from power, and that was in Meiwa six (明和, 1769) after 15 years into his tenure as a Daimyō and on orders of the Shōgunate, which forced him to retire, as it was of the opinion that his fief reform measures were not as successful as desired. So, the year after his removal from office, Shigeyoshi moved back to Edo, but returned once again to Tokushima in An’ei two (安永, 1773) for a medical treatment. After recovering, however, he lived quite the high live down on Shikoku, which once again upset the Shōgunate, which wanted him to come back to Edo to live in house arrest in the Edo residence of the Tokushima fief to enable a more effective Bakufu supervision. Well, Shigeyoshi was able to avoid that by moving to a different local residence in Awa province, where he eventually died in Kyōwa one (享和, 1801) at the age of 64.

Last but not least, I wanted to add that Shigeyoshi was also “otherwise” quite active. He had 16 sons and 14 daughters with his wife Tsutehime (伝姫 , 1737–1802) and with his concubines, of which there were at least four.